HEADNOTE

Evenings at Home; or The Juvenile Budget Opened. Illustrated with Engravings after Harvey and Chapman, by Adams. Revised edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852.

Evenings at Home is a collection of stories published by British siblings Anna Laetitia Aikin Barbauld and John Aikin. The book circulated widely in multiple editions across nineteenth-century decades to appreciative audiences in both Britain and America. The collection’s enduring popularity aligned with its blending of didactic appeals to nineteenth-century morality and a simultaneous commitment to entertaining children in a family setting.

Many of the stories are fables that incorporate animals used as a dialogical tool that children can identify with as they learn lessons for entering middle-class society (Howard). Often, the animals embody different vices or virtues. In ‘The Flying Fish’, the fish represents the vice of being discontented and prideful, a pattern which leads to her having to keep the wings she originally asked for, though they prove to be a burden. The text’s pedagogical method of utilizing animals allows for accessibility and potentially appeals to both children and the parents who would read to them.

When Evenings at Home first appeared, both Anna Laetitia Aikin Barbauld and her co-editor brother John Aikin were already well known through the family’s longstanding educational leadership. Anna Barbauld, along with her husband, ran a boarding school for boys from 1774 to 1785. Meanwhile, her brother John Aikin was a part-time lecturer at Warrington, where he had previously studied and lectured in a variety of subjects, including anatomy, physiology, and chemistry (Ready). This shared background as educators expanded through the publishing of Evenings at Home, which allowed them to amplify their collaborative pedagogical outreach to a sustained transatlantic stage.

See also, in the print anthology, an excerpt from Barbauld’s Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, A Poem, in the NC section, and an excerpt from her influential primer, Lessons for Children, in the print collection’s FD section. See too, in this section of the digital anthology, another entry from Evenings at Home, also in FD: ‘The Little Philosopher’.

Editorial work on this entry by Danielle Anderson

‘The Flying Fish’ from Evenings at Home (1796)

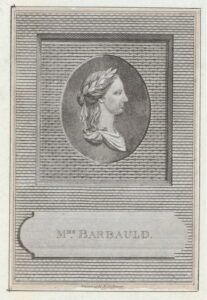

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Mrs. Barbauld.”

THE flying fish, says the fable, had originally no wings, but being of an ambitious and discontented temper, she repined at being always confined to the waters, and wished to soar in the air. “If I could fly like the birds,” said she, “I should not only see more of the beauties of nature, but I should be able to escape from those fish which are continually pursuing me, and which render my life miserable.” She therefore petitioned Jupiter1Roman God of the sky. for a pair of wings; and immediately she perceived her fins to expand. They suddenly grew to the length of her whole body, and became at the same time so strong as to do the office of a pinion.2The outer part of a bird’s wing including the flight feathers.

George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Flying fish.”

She was at first much pleased with her new powers, and looked with an air of disdain on all her former companions; but she soon perceived herself exposed to new dangers. When flying in the air, she was incessantly pursued by the tropic bird and the albatross; and when for safety she dropped into the water, she was so fatigued with her flight, that she was less able than ever to escape from her old enemies the fish. Finding herself more unhappy than before, she now begged of Jupiter to recall his present; but Jupiter said to her, “When I gave you your wings, I well knew they would prove a curse; but your proud and restless disposition deserved this disappointment. Now, therefore, what you begged as a favour, keep as a punishment!”

Source Text:

Aikin, Dr. [John] and Mrs. [Anna Laetitia] Barbauld. “The Flying Fish.” Evenings at Home; or The Juvenile Budget Opened. Illustrated with Engravings after Harvey and Chapman, by Adams. Revised edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852. 13-14 https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t6m04230q?urlappend=%3Bseq=25

References:

Howard, Darren. “Talking Animals and Reading Children: Teaching (Dis)Obedience in John Aikin and Anna Barbauld’s Evenings at Home.” Studies in Romanticism, vol. 48, no. 4, 2009, pp. 641-666,731. ProQuest,

Ready, Kathryn. “Dissenting Patriots: Anna Barbauld, John Aikin, and the Discourse of Eighteenth-Century Republicanism in Rational Dissent.” History of European Ideas, vol. 38, no. 4, 2012, pp. 527-549.

Image Citations:

Frontispiece. Aikin, Dr. [John] and Mrs. [Anna Laetitia] Barbauld. “The Flying Fish.” Evenings at Home; or The Juvenile Budget Opened. Illustrated with Engravings after Harvey and Chapman, by Adams. Revised edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t6m04230q&view=1up&seq=11

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. “Mrs. Barbauld.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Courtesy The New York Public Library. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47dc-8322-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

George Arents Collection, The New York Public Library. “Flying fish.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. Courtesy The New York Public Library https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-3a72-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99