HEADNOTE

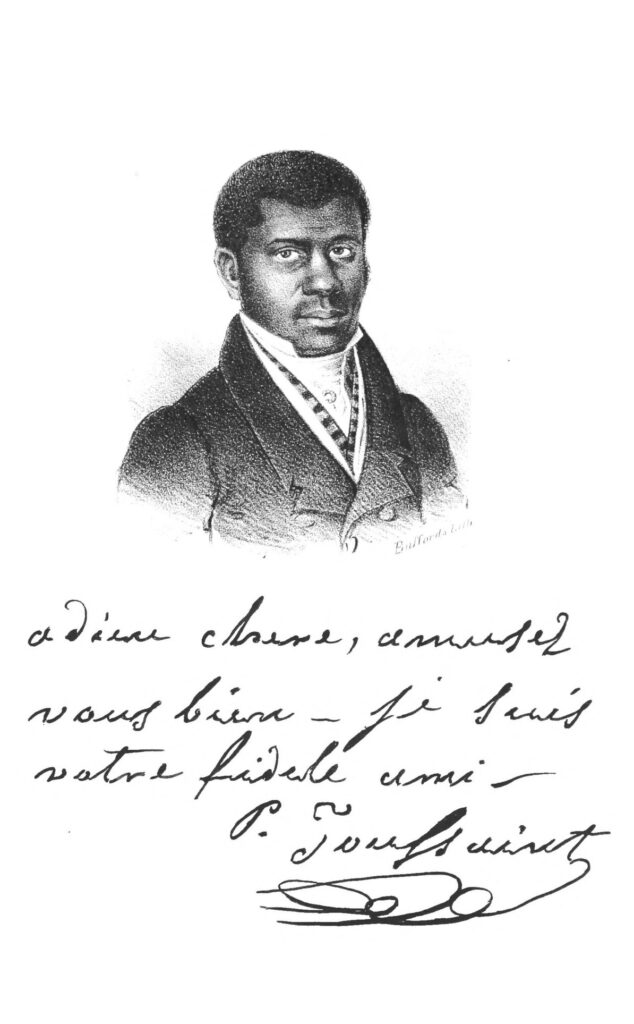

Pierre Toussaint was enslaved at birth in Saint Domingo, a French colony in Haiti, in 1766. He lived in St. Domingo until 1787 when his enslaver, Jean-Jacques Bérard, moved his wife Marie Elizabeth Bérard, along with Toussaint and a number of other enslaved persons to New York as a result of political turmoil in Haiti.

While in New York, Toussaint established a hairdressing business, a career that elevated him to a social status above other enslaved peoples, that served New York City’s upper-class. He found great success through this career and used his earnings to purchase his own home, investments, and the freedom of his sister Rosalie and of his future wife Mary Rose Juliette. After the death of Bérard in 1788, Toussaint most notably used his earnings to support and show his loyalty to his ‘mistress’, Mary Elizabeth. She later granted Toussaint freedom in 1807 right before her death that year.

Toussaint met Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee, the author of his memoir, through her sister Mary Anna Schuyler. Toussaint was a hairdresser to the Schuyler women and was a close friend of Mary Anna. Upon Mary Anna’s request, Lee wrote Toussaint’s narrative (Jones, 121, 209). In the memoir Lee showcases an account of Toussaint’s life but her commentary reveals a racist undertone when sharing that Toussaint acted and lived differently than other enslaved, or formerly enslaved, persons. Her racial bias influences how his story has been told and as a result many scholars have criticized Lee for her white lens in the narrative. Aside from Toussaint’s memoir, Lee’s other works include Three Experiences in Living (1837), Historical Sketches of Old Painters (1838), and Familiar Sketches of Sculpture and Sculptors (1854).

Toussaint’s transatlantic movements from Haiti to New York mirror his Catholic faith which has its own global and transnational influence. Religion, including the Catholic Church, had a significant role in the colonization of Haiti and the Caribbean more broadly, including in the institution of slavery in that region. For Toussaint, his Catholic faith was a transformative force on which he centered his life. Toussaint’s example went on to shape the faith of others and in 1996, Pope John Paul II declared Toussaint venerable, the first step in the process to sainthood due to Toussaint’s consistent devotion in supporting those in need, much of which was recorded in the memoir. The following excerpt showcases how others experienced Toussaint’s devotion to the Catholic faith through his Christ-like actions. This is primarily seen through correspondences he received from friends in places such as Rome, Port-au-Prince, and St. Thomas. These letters demonstrate Toussaint’s character, and the final part of the memoir delineates him as the Catholic figure he is known as today.

Headnote and editorial work on this entry by Nataly Dickson, TCU.

Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, Born a Slave in St. Domingo (1854)

PART THIRD.

THE period in Toussaint’s life which occurred from the time of Euphemia’s death for a succession of years seems to have been an uncommonly tranquil one.1Toussaint’s niece, whom he legally adopted. Also known as Euphémie (Jones, 2) His union with Juliette was happy. She was the daughter of a respectable woman named Claudine Gaston, who came to this country as a nurse, as has been before mentioned, with a French family, by whom she was much beloved. She was a judicious and an affectionate wife, by her neatness and order making his house pleasant to him, and taking a more than equal share in the labors of the family.

Every man must value the respect of his wife, and Toussaint could not but be gratified with the evident delight Juliette received from the attentions paid him. When her friends congratulated her on having such a good husband, her frank, happy smile, displaying rows of white teeth, gave a full assent to their commendations.

Toussaint said of himself, that he possessed a quick temper, that he was born with it, and was obliged to bear it about with him. We doubt not that it was true, because he had a lively sensibility to every thing; yet to those who knew his self-command and forbearance, this trait made him the more interesting. One of his intimate friends, in alluding to his confessions and penitence on the subject, said: “I never heard him speak ill of any one; if he could say no good, he was silent. Even those who were ungrateful to him met with no angry rebuke; it seemed to be his object to forget all injuries.”

Toussaint had a quick sense of the ridiculous, and like most of his race, when he was young, was an excellent mimic; as he grew older he relinquished this power, so amusing to others as a dangerous one.2One of the most common pieces of criticism Lee received is based around the lens through which she, a white woman, writes about Toussaint, a black, formerly enslaved man. He played on the violin for small dancing parties at one time, and taught one or two boys to play on this instrument, saying, if they did not derive profit from it, it would at least be an innocent amusement.

One of the methods in which Toussaint did essential good was by bringing up colored boys one after another, sending them to school, and, after they were old enough, teaching them some useful business. In all these plans of charity Juliette united.

The neatness and order of their household was striking. Toussaint purchased a pleasant and commodious house in Franklin Street, and a gentleman of the highest respectability took rooms there for some months.3Owning property was a mark of both economic success and social status which aligns with Toussaint’s career as a hairdresser. From a note of his I have permission to make extracts: —

“I am sorry to hear that Toussaint is on his death-bed, though I do not believe he has cared much about living since he lost his wife. Such was the even tenor of his way while I lived under his roof, that nothing occurs particularly to my memory. You know there is no being on earth who presents so few prominent and recollectable points as a ‘perfect gentleman.’ If you undertake to describe any such person whom you have ever known, you will find him the most indescribable. So it was with Toussaint. His manners were gentle and courtly; — how can this simple statement be expanded into details, so as to give a better idea of them? The most unaffected good humor at all times, the most respectful and polite demeanor without the slightest tincture of servility, the most natural and artless conversation, –all this I remember of him, as every one else remembers who knows him; but all his intercourse was so unobtrusive that it is difficult for me to recall anything marked. I remember how much I was pleased with his deportment and behavior towards his wife. Juliette was a good woman, but unlike Toussaint; she was flesh and blood, while he was possessed of the spirit of one man out of many thousands, I never met with any other of his race who made me forget his color. Toussaint, for his deportment, discretion, good sense, and entire trustworthiness and fidelity, might have discharged creditably all the functions of a courtier or privy councillor. His politeness, which was uniform, never led you for a moment to suspect his sincerity; it was the natural overflow, the inevitable expression of his heart, and you no more thought of distrusting it than of failing to reciprocate it, and I cannot imagine that any one could offer him an indignity.”

Such is the testimony of a gentleman thoroughly acquainted with the world. I remember Juliette’s opening a drawer and saying, “This is Mr. ———’s linen, I have all the care of it”; and it certainly did her the greatest credit.4It was a 19th-century convention to use a dash in place of giving an exact name to protect an individual’s privacy. Citizens who had not explicitly given permission to quote them or disclose private comments could be protected from public view through this convention.

We have no authority to say much of Toussaint’s views of slavery; in that, as in all things else, he acted rather than theorized. As we have seen, his earnings, all that he did not spend on the comfort of his mistress, were carefully hoarded for his sister’s freedom, and his wife’s freedom he purchased before he married her. We cannot doubt how highly he prized liberty for the slave, yet he was never willing to talk on the subject. He seemed to fully comprehend the difficulty of emancipation, and once, when a lady asked him if he was an Abolitionist, he shuddered, and replied, “Madame ils n’ont jamais vu couler le sang comme moi,” “They have never seen blood flow as I have”; and then he added, “They don’t know what they are doing.”5Toussaint has received criticism about his lack of involvement in the abolitionist movement. See ‘Canonizing a Slave: Saint or Uncle Tom?’ New York Times, 23 Feb 1992, pg. 1 (Sontag).

When Toussaint first came to this country, the free negroes and some of the Quakers tried to persuade him to leave his mistress. They told him that a man’s freedom was his own right. “Mine,” said he, “belongs to my mistress.”

When the colored people in New York celebrated their release from bondage, on the 5th of July 1800, they came to Toussaint to offer him a prominent part in the procession. He thanked them with his customary politeness, congratulated them on the great event of emancipation, but declined the honor they assigned him, saying, “I do not owe my freedom to the State, but to my mistress.”

There are so many instances of his devotion to the sick that we do not particularize them; but one lady mentions, that when the yellow fever prevailed in New York, by degrees Maiden Lane was almost wholly deserted, and almost every house in it closed. One poor woman, prostrated by the terrible disorder, remained there with little or no attendance; till Toussaint day by day came through the lonely street, crossed the barricades, entered the deserted house where she lay, and performed nameless offices of a nurse, fearlessly exposing himself to the contagion.

At another time he found a poor priest in a garret, sick of the ship-fever, and destitute of every thing. He made his case known, procured him wine and money, and finally moved him to his own house, where he and Juliette attended upon him till he recovered.

A friend once said to him, “Toussaint, you are richer than any one I know; you have more than you want, why not stop working now?” He answered, “Madam, I have enough for myself, but if I stop work, I have not enough for others.”

By the great fire of 1835, Toussaint lost by his investments in insurance companies.6On 16 December 1853, the most destructive fire in the history of New York City took place. It destroyed more than 700 buildings (Williams, 38). Some of his friends, who knew of his slow, industrious earnings, and his unceasing charities, thought it but just to get up a subscription to repair his losses. As soon as it was mentioned to him he stopped it, saying he was not in need of it, and he would not take what many others required much more than he did.

Among the numerous letters which Toussaint received, there are many from foreign parts. Persons of rank and high consideration wrote to him for years.

In 1840 Toussaint received the following letter from a friend at Port-au-Prince: —

“My dear Toussaint: —

“You will receive this by the Abbé ———, who has left this country because he could not exercise his functions as a priest of God ought to be able to do. His holy duties are shackled by laws which subject him every moment to judges, who, according to the rules of our faith, are not competent to direct a priest in his duties as a minister of God. For reasons like these, he leaves this country; but he can inform you on this subject better than I can.”

This gentleman was received by Toussaint with much respect and cordiality. He left New York very shortly, and a few months after, a letter, from which we make the following extracts, reached Toussaint: —

“Rome, 1841.

“My very dear friend: —

“You are no doubt surprised not to have heard from me since I left New York, but I can assure you this omission has not arisen from forgetfulness of you or your dear wife. On the contrary, I have thought of you constantly, but my engagements have prevented my writing until now.

“On my arrival in this city, I was presented to the Propaganda, and was received by his Eminence Cardinal Fransoni with much attention and kindness.7Reference to Congregation of the Propaganda, a committee responsible for foreign missions. Most recently known as the College of the Propaganda which trains missionaries for evangelization (Oxford English Dictionary). I was offered other missions, but I preferred and received permission to continue my studies at Rome for two years in the College of the Twelve Apostles, and the Propaganda pays all the expense during my residence in Rome. To-day for the first time I put on the Roman ecclesiastical habit. I have received permission from the Cardinal Vicar-General of the Pope, to celebrate the Holy Mass in all the churches of Rome. There are, I believe, four hundred, some of them the largest and finest in the world; indeed they are little heavens upon earth, adorned with every thing which can be procured in gold, silver, hangings of silk and satin, in marble statuary, in paintings, and mosaics. I wish I could give you a more minute account. Present my respects to the Rev. Mr. Powers, and believe me that I hold you and your kind wife in constant remembrance. With my best wishes for your temporal and eternal welfare, permit me to subscribe myself.

“Your very sincere friend.”

We add a few extracts of letters from his own race. The following is from Constantin Boyer: —

“Port-au-Prince, 1836.

“My dear friend: —

“I begin by wishing you a happy new year, as well as to madam, your wife. However, it is only wishing you a continuation of your Christian philosophy, for it is that which makes your true happiness. I do not understand how any one can have a moment’s peace in this world if he does not have constant reference to God and his holy will.”

Another colored friend in Port-au-Prince writes as follows: —

“1837.

“You wish me prosperity, dear friend; what can touch my heart more than to receive your benediction, — the benedictions of a religious man. I have known many men and observed them closely, but I have never seen one that deserved as you do the name of a religious man. I have always followed your counsels, but now more than ever, for there are few like you. Good men are as rare as a fine day in America.”

The following is from a colored woman to Madame Toussaint: —

“Port-au-Prince, 1844.

“This is the second letter I have written to you without waiting for an answer; but the gratitude I owe to you, my very dear friend, and to your husband, induces me to write, every good opportunity. After the services and the kindness you have shown me, during my residence in New York, I hope I never shall forget you. Since our arrival here, we have been in constant trouble and anxiety; the country is not tranquil. I fear that we shall be obliged to return to Jamaica again. At the other end of the coast, more than twelve hundred persons have gone to Jamaica. We are in a country where you can get no one to serve you or to help you. They all tell you they are free, and will serve no one.”

The following extract is from a letter by a colored friend: —

“Port-au-Prince, 1838.

“Let us now speak of politics. I have the honor to send you the treaty between France and Hayti, that you may see the conditions of agreement between the two powers.8Possible reference to the ‘Treaty of Friendship’ or ‘Traité d’Amitié’; ‘Treaty of Peace and Friendship’. If I were to give you all the details, I should have to w9Constantin Boyer, one of Toussaint’s friends from Haiti, lived in New York, but returned to his home country and established a grocery store in Port-au-Prince (Laguerre, 53).rite a journal. But you will have them before your eyes. I can tell you, however, that since the arrival of Baron de Lascase there has been nothing but fêtes, dinners, breakfasts, and balls, in the city and the environs.10This sentence is a possible reference to Emmanuel, Count de las Cases, also known as Emmanuel de Las Cases (1766- 1842) (Britannica). The company consisted of the captains of frigates, the French Consul and his staff, generals, colonels, and other officers of Hayti. Would you believe that great numbers of persons wished to give them breakfasts, and could not? These gentlemen were always engaged by one or another. Le Baron de Lascase gave a ball to the Haytian ladies; never has any thing like it been seen in Port-au-Prince. The company was the captains of frigates and brigs, as well as their officers. Ah! it was a splendid ball. They left, the 22d of March, with two Haytian missionaries, who have gone to France to get a receipt for the money which has been given, and to see to the ratification of the treaty.

“The Chamber of Representatives is open since the 10th of April. I hope they will lower the duties, and that will give us a more open commerce, and be a great advantage to us. The President made a fine discourse at the opening of the Chamber, but I could not get it to send it to you. It will come by the next opportunity. I assure you that the Baron de Lascase has been very much pleased with the Haytian gentlemen. They left Port-au-Prince with regret, after having made such pleasant acquaintances. May God keep you, Sir, in his holy keeping! It is not we who will see the happiness of this country, but our children will. If they behave themselves well, they will enjoy the happiness which has been denied to their ancestors.”

The following is extracted from another letter of C. Boyer: —

“Port-au-Prince, June 13, 1842.

“My dear friend, do you know (unhappy country!) that there exists no longer Cape Haitien, nor Santiago, nor Port-au-Paix! These three cities were destroyed, on the 7th of May last, by an earthquake. While I speak of it, my hair stands on end. Never has living soul seen such a terrible earthquake. Santiago, such a pretty city, so well built, all with walls like the Cape, all houses of two or three stories high, all has been thrown down in half a second. At the Cape not a house stands upright. The trembling lasted for five minutes, rapidly, with great force. At Gonaive the earth opened, and a clear stream of water rushed out. At the same time, a fire broke out and consumed twenty houses. At Port-au-Paix the sea rose violently nearly five feet, and carried off the rest of the houses which had not fallen. At the Cape six thousand persons have been killed under the ruins, and two thousand wounded. At St. Domingo all the houses have not fallen; they are, however, nearly all shattered and uninhabitable. The shock was much more violent towards the north than at the south; but this gives you some idea of what has taken place in this poor country. It happened at half past five in the evening. This country is now most miserable.”

The following is from a young colored man: —

“St. Thomas, 1849.

“MY DEAR AND VENERABLE COMPATRIOT: —

“So far off as I am from you, I think of you always. I wend my way to Franklin Street at least once a day, in imagination, and the recollections of Boston or Lowell, of New York or Jersey City, never leave me. Yes, the Union is a beautiful thing (belle chose), and the United States is a beautiful country. It offers something much more beautiful than other countries. It is its love of order, of work, its industry, that makes it first among the nations. They are surprised in the Colonies at the enthusiasm with which I speak of the United States, because in general the men of our race here suppose that all people of color are treated like cattle there. I wish I could tell you something satisfactory of our country; but this gratification is a long way off. If there is not bloodshed, there are deceptions, iniquities, the same bad tendencies, —terror is the order of the day.”

The following is an extract from a letter from an old friend of Toussaint’s. It may be interesting from its touch of humor.

“Chicago.

“MY DEAR OLD COMPANION: —

“I am glad to hear that your horrible winter has neither killed you nor given you any serious illness. Thanks to your regular habits and your fervent prayers, you are still in good health, and I hear very prosperous. But you are still a negro. You may indeed change your condition, but you cannot change your complexion, —you will always remain black. Do they mistake you for a white man, that you have a passport everywhere? No; it is because you perceive and follow the naked truth. Many think that a black skin prevents us from seeing and understanding good from evil. What fools! I have conversed with you at night when it was dark, and I have forgot that you were not white. The next morning when I saw you, I said to myself, Is this the black man I heard talk last night? Courage! let them think as they please. Continue to learn, since one may learn always, and communicate your wisdom and experience to those who need it. I must now write to you about the ladies here. They are great coquettes, go with their heads well dressed, which they arrange themselves with great taste. Your business (hair-dressing) would be worth nothing here. You must not come to this place to make your fortune; it would be a bad speculation.”

We feel as if we had hardly done justice to the constant and elevated view which Toussaint took of his responsibility towards his own race. He never forgot that his color separated him from white men, and always spoke of himself as a negro. He sometimes related little anecdotes arising from this circumstance which amused him. One occurs to me that made him laugh heartily. A little girl, the child of a lady whom he often visited, came and stood before him, looking him steadily in the face, and said, “Toussaint, do you live in a black house?”

When he was very sick, a friend who was with him asked him if she should close a window, the light of which shone full in his face. “O non, Madame,” he replied, “car alor je serai trop noir”; —“O no, Madam, for then I shall be too black.” This humorous notice of his color, without the slightest want of self-respect was entirely in keeping with his character. He was a true negro, such as God had made him, and he never strove to be any thing else. The black men represented as heroes in works of fiction often lose their identity, and cease to interest us as representatives of their race, for they are white men in all but color. It was a striking trait in Toussaint, that he wished to ennoble his brethren, by making them feel their moral responsibility as colored men, not as aping the customs, habits, and conversation of white men. He never forgot that he “lived in a black house,” nor wished others to forget it.

For many years Toussaint’s life seems to have passed unmarked by any sorrows which do not occur to every one. He had accumulated what to his moderate views was an independence, and enabled him to assist others. Juliette’s mother lived with them, and was supported by him till she died. He had no connections of his own, but his kindness to all who needed it was unceasing. We think there are many who will recollect this period, and the cheerful little parlor where they convened their guests.

One of their social parties was pleasantly described to me by a white American acquaintance who had called on them, and whom Juliette invited with a companion to visit her. They belonged to the household of one of his most cherished and respected friends. They found only two Frenchwomen as guests besides themselves. The table was most neatly and handsomely set out, with snowy damask table-cloth and napkins, and exhibiting many of the elegant little memorials pertaining to the tea-table which had been sent them as presents from their friends in Paris. Juliette sat at the head, and waited on them, treating them with her delicious French chocolate, but of which she did not herself partake. When they had finished the repast, they went into the contiguous room, and Toussaint joined the party. It was thus his sense of propriety led him to draw the line. He never mingled the two races. This might have been in some measure the result of early teaching, but there was evidently a self-respect in avoiding what he knew was unwelcome.

We find a letter of Toussaint to Juliette, which we insert: —

“I have this moment received your letter, my dear wife, and I answer it on the spot. Every thing goes on well here. I have a great wish to see you, but I wish much more that you should remain as long as you are pleased to do so, for I love my wife for herself, not for myself. If you are amused at Baltimore, I hope you will remain some days longer with your good friends. I thank them for having received you so kindly. Present my compliments to Miss Fanny, and tell her that I hope she will not set you too many bad examples. I know that, though she is very devout, she is un péu mechante.11‘she is a little malicious.’ I hope you will bring away with you her devotion, but not her méchanceté.”12‘wickedness.’

There was often something sportive and paternal in Toussaint’s manner towards his wife, and when the difference in their ages was understood, it was easily accounted for. He had ransomed her when she was fifteen, and when he was himself in his thirty-seventh year. They were most truly attached to each other. “Je ne donnerois pas ma Juliette,” said he to one of his French friends, “pour toutes les dames du monde; elle est belle à mes yeux,” — “I would not give my Juliette for all the women in the world; she is beautiful in my eyes.”

Both of them enjoyed excellent health, and probably Toussaint never supposed he should be the survivor. It was otherwise ordered. Juliette’s health began to fail, and some alarming symptoms appeared. As in Euphemia’s case, he was sanguine that she would recover. He said, “She is much younger than myself, —she is strong, very strong. She is nervous, —she will soon be better.” But it became evident that she grew more ill, and he could no longer shut his eyes upon her danger.

“I often went to see Juliette,” said a friend to me. “Between her chamber and her husband’s there was a small room, which was fitted up with a crucifix, a prie-dieu, and many beautiful emblems of the Catholic faith, gifts to Toussaint, which he carefully treasured.13‘A piece of furniture for the use of a person at prayer, consisting of a kneeler with a narrow upright front surmounted by a ledge for books or for resting the elbows, and often a shelf below this for storing books, etc.’ (Oxford English Dictionary). ‘Ah,’ said she, ‘he prays for me there, —it is all the comfort he has; he will soon be alone. Poor Toussaint!’”

When her death came, it was a dreadful blow to him. He never recovered from the shock. It seemed to him most strange that she should go first, and he be left alone; yet he constantly said, “It is the will of God.” Soon after her death, his own health became impaired. The strong man grew feeble; his step slow and languid. We all saw that Toussaint was changed. Yet he lingered on, daily visiting beloved friends who sympathized in his great loss, and still continuing his works of beneficence.

We have adverted to the gayety and playfulness of Toussaint. They often met answering sympathies among his friends. We extract one or two passages from the letters of a lady who was travelling in Europe, and who well understood these traits in his character: —

“1849.

“I have returned from church. The service was performed in a Catholic chapel, with all the insignia. I thought of my dear Toussaint, and send my love to him. Tell him I think of him very often, and never go to one of the churches of his faith without remembering my own St. Pierre, and nobody has a better saint. I am glad to hear from him and his good Juliette.”

We add a short note from the same lady: —

“DEAR TOUSSAINT: —

“I go to the Catholic churches all over; they are grand and ancient. I always remember my own St. Pierre, and often kneel and pray with my whole heart. Ah, dear Toussaint, God is everywhere! I see him in your church, in mine, in the broad waste and the full city. May we meet in peace and joy. Ever and ever

“Your true friend.”

We find among Toussaint’s papers continual proof of his charitable gifts and loans, and of his efforts to discover any of his own family who might yet remain in St. Domingo, and also of the family of his aunt, Maria Boucman.14Toussaint is known as the father of Catholic Charities in New York according to the Archdiocese of New York. He also is known as raising money for the first Catholic orphanage NY and the city’s first school for black children among other charitable acts (‘Venerable Pierre Toussaint’). In his will he sets aside four hundred dollars to be paid to her descendants in case they can be found within two years.

His health was now evidently failing, yet morning after morning, through snow and ice and wintry frost, his slow and tottering step was seen on his way to Mass, which he never once failed to attend for sixty years, until a few months before his death; and later in the day, his aged frame, bowed with years, was to be seen painfully working its way to a distant part of the city, on errands of love and charity. A friend said to him thoughtlessly, “Toussaint, do get into an omnibus.” He replied, with perfect good humor, “I cannot, they will not let me.”

One bitter pang remained for him; to watch by the death-bed of that being who, from her exalted station, had poured strength and consolation into his wounded heart; who had often left the gay circles of fashion to speak to him words of peace and kindness, and who, when the shadows of death were coming over her, gave orders that Toussaint should always be admitted. Many were the fervent and silent prayers that the aged man breathed by the side of her bed, with clasped hands and closed lips.

Toussaint was a devoted disciple of his Church; her books of instruction were his daily food, his prayer-book was always in his pocket, and the maxims of Thomas à Kempis were frequently introduced in his serious conversation.15Renaissance Roman Catholic monk (1380-1471) known for The Imitation of Christ (1418-1427) His illustrations were often striking. In speaking to a Protestant friend of the worship of the Virgin, he said, turning to a portrait of a near relation of hers in the room, “You like to look at this: it makes you think of her, love her more; try to do what she likes you to do.” In his interesting manner he described his own feelings towards the pictures and images of the Virgin Mary.

As he grew more feeble he was obliged to give up his attendance on the church. This occasioned him some depression. One of his Protestant friends who observed it said, “Shall I ask a priest to come and see you? Perhaps you wish to confess.” After a long pause he said, “A priest is but a man; when I am at confession, I confess to God: when I stand up, I see a man before me.”

His simple method of expressing his convictions was striking, and often instructive. He was enlightened in his own faith, not from reading, but from a quick perception of the truth.

A lady who had known Toussaint from her childhood wrote a letter when she heard of his illness, from which the following passages are quoted: —

“If my mother were living, how much she could tell us of Toussaint! But unfortunately I never kept notes of the many incidents she used to relate of his character; I regret it sincerely now. At the time of Euphemia’s death we were in France, but most deeply did we feel for him.

“When we returned I saw him constantly, and began to comprehend him, which I never did fully before. I saw how uncommon, how noble, was his character. It is the whole which strikes me when thinking of him; his perfect Christian benevolence, displaying itself not alone in words, but in daily deeds; his entire faith, love, and charity; his remarkable tact, and refinement of feeling; his just appreciation of those around him; his perfect good taste in dress and furniture, —he did not like any thing gaudy, and understood the relative fitness of things. He entertained an utter aversion to all vain pride and assumption. He spoke of a lady he had known in poverty who was suddenly raised to wealth. She urged him to call and see her. He was struck with the evident display of her riches. She talked to him of her house, her furniture, her equipages, her jewels, her dresses; she displayed her visiting cards with fashionable names. To all this Toussaint silently listened. ‘Well,’ said she, ‘how do you like my establishment?’ ‘O madam!’ he said, ‘does all this make you very happy?’ She did not answer; she was not happy, poor woman! She was poor in spirit; she never knew the pleasure of making others happy.

“I recollect how invariably he consulted the dignity of others, as well as his own. A lady was staying with me, and being a Roman Catholic, she wished to go to St. Peter’s Church, and asked Toussaint for a seat in his pew, on Sunday morning.16St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church in New York City. He said, ‘Certainly, madam, you shall be accommodated.’ I went with her to Barclay Street; we found him waiting at the door. He conducted her to Madame Depau’s pew, which was vacant. ‘I expected to sit in your pew,’ said she. ‘No, madam,’ he replied, ‘it would not be proper.’ Though he labored under the disadvantage of speaking a language imperfectly, it being late before he became familiarized with English, he seemed always to say just what was proper, and what any one who knew him would expect him to say. His religion was fervent, sincere, and made a part of himself; it was never laid aside for worldly purposes. You must not think from these remarks that Toussaint was a grave, solemn man; he was full of spirit and animation, and most entertaining in his little narratives. I have laughed merrily at his anecdotes and remarks, and when my sister and I were girls, he used to dance for us as they danced when our parents were young; and though the style was so different, his attitudes were easy and graceful. Though very discriminating, and meeting with amusing things in various families, he was careful never to repeat what passed in different houses, much less to betray the slightest confidence placed in him. How much I regret that I cannot be near him at the last! but I have the satisfaction of knowing ‘all is well.’”

Many other touching remembrances might be added. One French lady said: “He dressed my hair for my first communion; he dressed it for my wedding, and for christenings, for balls and parties; at burials, in sickness and in trouble, he was always here.”

Another said: “The great fire of 1835 changed our fortunes; the first person who came to us early the next morning was Toussaint, to proffer his services and sympathy.”

There is but little to add to this memorial. When I last saw Toussaint, I perceived that his days were numbered; that he stood on the borders of the infinite. He was feeble, but sitting in an arm-chair, clad in his dressing-gown, and supported by pillows. A more perfect representation of a gentleman I have seldom seen. His head was strewed with the “blossoms of the grave.” When he saw me he was overcome by affecting remembrances, for we had last met at the funeral obsequies of the friend so dear to him. He trembled with emotion, and floods of tears fell from his eyes. “It is all so changed! so changed!” said he, “so lonely!” He was too weak to converse, but his mind was filled with images of the past, of the sweet and noble lady to whose notes we are indebted. The next day I saw him again, and took leave of him to see him no more in this world. It was with deep feeling I quitted his house, —that house where I had seen the beings he dearly loved collected. It was a bright summer morning, the last of May; the windows were open, and looked into the little garden, with its few scattered flowers. There was nobody now I had ever seen there, but himself, —the aged solitary man!

I left the city, and in early June received notes from a friend who had visited him daily for months. From these I transcribe.

“Toussaint was in bed to-day; he says it is now the most comfortable place for him, or as he expressed it in French, ‘Il ne peut pas être mieux.’17‘it can’t get any better.’ He was drowsy and indistinct, but calm, cheerful, and placid, —the expression of his countenance truly religious. He told me he had received the last communion, for which he had been earnest, and mentioned that two Sisters of Charity had been to see him, and prayed with him. He speaks of the excellent care he receives, —of his kind nurse (she is a white woman), —and said, ‘All is well.’ He sent me away when he was tired, by thanking me.”

A few days after, I received the following note: —

“Excellent Toussaint! he has gone to those he loved. His departure took place yesterday at twelve o’clock, without pain or suffering, and without any change from extreme feebleness. I saw him on Sunday; he was very low, and neither spoke nor noticed me.

“On Monday, when I entered, he had revived a little, and looking up, said, ‘Dieu avec moi,’ —‘God is with me.’ When I asked him if he wanted any thing, he replied with a smile, ‘Rein sur la terre,’ —‘Nothing on earth.’

“I did not think he was so near the gates of heaven; but on Thursday, at twelve o’clock, his spirit was released from its load. He has put off his sable livery, and is clothed in white, and stands with ‘palms in his hands, among the multitude of nations which no man can number.’18Reference to Revelation 7:9 “After this I had a vision of a great multitude, which no one could count, from every nation, race, people, and tongue. They stood before the Lamb, wearing white robes and holding palm branches in their hands” (New American Version). The verse refers to the various images presented in the book of Revelation related to what one will see either at the end of someone’s life, or the end of time for all. How much I shall miss him every day, for I saw him every day, —every day!”

The following note is of a still later date: —

“I went to town on Saturday, to attend Toussaint’s funeral. High mass, incense, candles, rich robes, sad and solemn music, were there. The Church gave all it could give, to prince or noble. The priest, his friend, Mr. Quin, made a most interesting address. He did not allude to his color, and scarcely to his station; it seemed as if his virtues as a man and a Christian had absorbed all other thoughts. A stranger would not have suspected that a black man, of his humble calling, lay in the midst of us. He said, ‘Though no relative was left to mourn for him, yet many present would feel that they had lost one who always had wise counsel for the rich, words of encouragement for the poor, and all would be grateful for having known him.’

“The aid he had given to the late Bishop Fenwick of Boston, to Father Powers of our city, to all the Catholic institutions, was dwelt upon at large. How much I have learnt of his charitable deeds, which I had never known before! Mr. Quin said, ‘There were few left among the clergy superior to him in devotion and zeal for the Church and for the glory of God; among laymen, none.’

“The body of the church was well filled with men, women, and children, nuns, and charity sisters; likewise a most respectable collection of people of his own color, all in mourning. Around stood many of the white race, with their eyes glistening with emotion. When Juliette was buried, Toussaint requested that none of his white friends would follow her remains; his request was remembered now, and respected; they stood back as the coffin was borne from the church, but when lowered to its last depository, many were gathered round his grave.”

Thus lived and died Pierre Toussaint; and of him it may be truly said, in the quaint language of Thomas Fuller , an old English divine, that he was “God’s image carved in ebony.”19Thomas Fuller, 1608-1661. British scholar, preacher, prolific author of the 17th century (Britannica).

Source text:

Lee, Hannah Farnham Sawyer. Memoir of Pierre Toussaint: Born a Slave in St. Domingo, 2nd edition (Boston: Crosby, Nichols, and Co., 1854), 80-115.

References:

Davis, Cyprian. ‘Black Catholics in Nineteenth Century America’, U.S. Catholic Historian, 5.1 (1986), 1–17.

Goldman, Maureen. ‘Lee, Hannah (Farnham) Sawyer’, in Taryn Benbow-Pfalzgraf (ed.,), –American Women Writers: A Critical Reference Guide from Colonial Times to the Present, 3 vol., 2nd ed., (Detroit: St. James Press, 2000), 3: 26-7.

Jones, Arthur. Pierre Toussaint. (New York: Doubleday, 2003).

Laguerre, Michel S. Diasporic Citizenship: Haitian Americans in Transnational America (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998).

Shelley, Thomas J. ‘BLACK AND CATHOLIC IN NINETEENTH CENTURY NEW YORK CITY: THE CASE OF PIERRE TOUSSAINT’, Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, 102.4 (1991), 1–17.

‘Venerable Pierre Toussaint.’ Archdiocese of New York: Cultural Diversity Apostolate. https://archny.org/ministries-and-offices/cultural-diversity-apostolate/black-ministry/venerable-pierre-toussaint/

Williams, Jasmin K. ‘THE GREAT FIRE OF 1835.’ New York Post (NY) 6 Nov. 2008, p. 038.

Image Reference:

Portrait of Pierre Toussaint. Memoir of Pierre Toussaint: Born a Slave in St. Domingo, 2nd edition (Boston: Crosby, Nichols, and Co., 1854), 80-115. Courtesy of HathiTrust.