HEADNOTE

Hans Christian Andersen was born in April 1805 in Odense, a quaint and picturesque city in Denmark. Although his childhood was plagued by poverty and the possibility of following his late grandfather into insanity, the famous fairy-tale author held a spirited love for life. Travel was one of his passions, and in ‘1833, Hans was granted a travelling stipend by King Christian VIII, and went to Paris, Switzerland and Italy’ (Belloc, 58). This adventure partially inspired him to publish his first set of Fairy Stories in 1835. But Andersen had affection for places beyond Europe and held a variety of interests in America as well.

Andersen’s relationship with America is complex, defined by his transatlantic popularity, the publication of his work overseas, and his personal connections. Many friends and acquaintances, especially ‘Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt (1820-87), an early romantic interest of Andersen’s,’ and Henriette Wulff, a close friend, encouraged Andersen to make the trip to America (Spiegel & Johnson, 52). In 1855 and 1856, Andersen consulted a map of America and made realistic plans for the journey overseas (Spiegel & Johnson, 53). However, Miss Wulff’s tragic death at sea en route to America in September 1858 caused Andersen to develop a fear of ocean voyages and he never actually crossed the Atlantic (Bredsdorff, 235).

But avid fans of Andersen in America, such as children’s author Horace Scudder, initiated correspondence with him to publish his work abroad. ‘Scudder wrote to and about Andersen and published a number of his stories in The Riverside Magazine’ (Spiegel & Johnson, 57).Several of Andersen’s tales, including ‘Great-Grandfather’, were published in English in The Riverside Magazine ‘in 1868, 1869, and 1870, prior to their publication in Danish’ (Bredsdorff, 260). For more on Andersen’s other American translators, publishers, and early transatlantic stories, see ‘The Little Match-Girl’ on page 160 in the BIL section of the print anthology.

‘Great-Grandfather’ serves as Andersen’s commentary on the changing ways of the world. The story’s emphasis on generational differences in the opinions on progress and technological innovation is a relatively far cry from his usual fantastical tales. According to Dr. Eric Dal’s ‘Hans Christian Andersen’s Tales and America’, ‘one of the more substantial [generalizations] must be said to be the concept of the USA as the country of technical inventions and material pioneering’ (Dal, 7). Andersen’s positive perspective on such topics recurs so often in his works that he seems to be adopting a shared view then prevalent in transatlantic culture. In this story specifically, Andersen references the wonders of daguerreotypes, praises the telegraph, and includes a quick ode to Hans Christian Örsted, ‘the discoverer of electromagnetism’ and ‘an object of his deep affection and devoted respect’ (Dal, 8).

Hans Christian Andersen uses the characters of great-grandfather and Frederick to display the complex nature of innovation’s effects on both the older and younger generations. This conflict was reflected in Andersen’s own life, for although he was part of the ‘cosmopolitan intelligentsia’ of the time, he was also known for his political ambivalence and faced anxiety about popular socialist movements (Spiegel & Johnson, 50). ‘This ambiguity is mirrored in the story Great-Grandfather, cleverly exemplifying the eternal tension and friction between the viewpoints of two generations’ (Dal, 8).

Editorial work on this entry by Colleen Wyrick.

‘Great-Grandfather’ (1870)

Hallager, Thora. “Hans Christian Andersen.” Photograph. Great Norwegian Encyclopedia, 1867.

GREAT-GRANDFATHER was so lovable, wise, and good! We all looked up to great-grandfather. He used to be called, as far back as I can remember, “Father’s-father,” and also “Mother’s-father;” but when brother Frederick’s little son came into the family, he was promoted, and got the title of “Great-grandfather.” He could not expect to get any higher!

He was very fond of us all, but our times he did not seem fond of. “Old times were good times,” he used to say; “quiet and steady-going they were; in these days there is such a hurrying and turning upside-down of everything. The young people lay down the law, and speak of the kings, even, as if they were their equals. Any good-for-nothing fellow can dip a rag in rotten water, and wring it out over the head of an honorable man!”

Great-grandfather would get quite angry and red in the face, when he talked of these things; but very soon he would smile his kind, genial smile, and say, “Well, well! I may be mistaken; I belong to the old times, and can’t quite get a foot-hold in the new! May God lead and guide us aright!”

When great-grandfather got to talking of old times, it seemed to me that I was living in them, so clearly did I see it all. Then I fancied myself driving along in a gilt1Covered with a thin coating of gold, esp. with gold leaf, or (in later use) an imitation of this; decorated with gilding (OED) coach, with fine liveried2Esp. of a domestic servant: dressed in or wearing a livery; provided with a livery. (OED) servants standing on the step behind; I saw the guilds move their signs, and march in procession, with banners, and with music at their head; I was present at the merry Christmas feasts, where games of forfeit were being played, and where the players were dressed in fancy dress and mask. It is true that in those old times cruel and dreadful things used to happen, such as torture, and rack, and bloodshed; but all these horrors had something stirring about them that fascinated me. I used to fancy how it was when the Danish lords gave the peasants their liberty, and when the Crown Prince of Denmark abolished the slave-trade. 3Under King Christian VII, Denmark abolished the slave trade in the spring of 1792, although the ban didn’t go into full effect until 1803. Still, Denmark was the first slave-trading nation to abolish its slave trade, which is likely why Andersen felt the need to mention its historical excellence here (Gøbel 9).

Als, Peder, and Gotthard Wilhelm Åkerfelt. “Portrait of Christian VII, King of Denmark and Norway.”

It was famous to hear great-grandfather tell of all this, and to hear him speak of his youth. But I think the times before that, even, were the very best of all, – so strong and great!

“It was a rude time!” said brother Frederick; “thank God we are well out of it!” And he used to say this right out to great-grandfather: that was very improper, I know, but I had great respect for Frederick all the same. He was my oldest brother, and he said he was old enough to be my father, – but then he said so many odd things. He had graduated with honors, and was so bright and clever at his work in father’s office, that father intended to take him into partnership soon. He was the one, of us all, that great-grandfather talked most to; but they did not get on well, and always fell to arguing; they did not understand each other, those two, – and never would, said the family; but, small as I was, I soon saw that neither of them could do without the other. Great-grandfather used to listen with the brightest look in his eyes, when Frederick read aloud about the progress in science, or new discoveries of natural laws, and of all the other wonders of our age.

“The human race grows cleverer, but not better,” great-grandfather used to say; “they take pains to contrive the most dreadful and hurtful weapons, wherewith to kill and maim each other.”

“So much the sooner will the war be over,” Frederick would reply; “then one need not wait seven years for the blessing of peace. The world is full-blooded, and needs a blood-letting from time to time – that is a necessity.”

One day Frederick told him of something that had really happened in a small country, and in our age. The mayor’s clock – the large clock on the City Hall – marked the time for the city, and for all its inhabitants. The clock did not go very well, but that did not matter, nor prevent everybody from being guided by it. Then by and by railways4Andersen traveled by railway for the first time in 1840. His emotions over the matter were recorded in a letter he wrote to Edvard Collin. “‘I am delighted, oh! If only you and all the others at home had been with me! Now I know what flying means! Now I know the flight of the migratory birds, or that of the cloud when it hurries on above the earth,’” (Bredsdorff 202). were built in that country, and clocks are always connected with the railways in other countries, – so that one must be very sure of the time, and know it very exactly, or else there will be collisions. At the railway station they had a sun-regulated clock that was perfectly reliable and exact, – but not so the mayor’s, – and now everybody went by the railway clock.

I laughed, and thought it was a funny story, but great-grandfather did not laugh; he grew very serious.

“There is a deep meaning in what you have been telling me,” he said, “and I understand the thought that prompted you to tell it to me. There is a moral in that clock-work; it makes me think of another clock, – my parents’ plain, old-fashioned Barnholm clock, with leaden weights. It was the time-measurer for their lives, and for my childhood. I dare say it did not go very correctly, but it did go, and we used to look at the hour-hand, and believed in it, and never thought about the wheels inside. The government machinery was like that old clock; in those days everybody had faith in it, and only looked at the hour-hand. Now the government machinery is like a clock in a glass case, so that one can look right into the machinery, and see the wheels turning and whizzing: one gets quite anxious, sometimes, as to what will become of that spring, or that wheel! And then I think how will it be possible for all this to keep time? and I miss my childish faith in the faultlessness of the old clock. That is the weakness of these times!”

And then great-grandfather would talk till he got quite angry. He and Frederick did not agree well, and yet they could not bear to be separated, – “just like the old times and the new.” They both felt this when Frederick was to start on his journey, – far away, to America. It was on business for the firm, that he had to go. A sad parting it was for great-grandfather, and a long, long journey, – quite across an immense ocean, and to another part of the globe.

“You shall have a letter from me every fortnight,” said Frederick, “and, quicker than by any letter, you will hear of me by means of the telegraph.5Any of various devices designed to convey messages over a distance using visible or audible signs or signals. The word telegraph was first applied to the semaphoric device invented by Claude Chappe in France in 1792, which consisted of an upright post with movable arms, the signals being made by positioning the arms according to a prearranged code. (OED) The days will be like hours, and the hours like minutes!”

Through the telegraph came a greeting from Frederick, from England, when he was going on board the steamer. Sooner than by letter – even if the quick-sailing clouds had been postmen – came news from America, where Frederick had gone on shore but a few hours since.

“What a glorious, divine thought this is, that is given us in this age,” said great-grandfather; “it is a real blessing for the human race.”

“And it was in our country,” I said, “that that law of nature was first understood and expressed. Frederick told me so!”

“Yes,” said great-grandfather, and kissed me; “and I have looked into the two kind eyes that were the first to see this wonderful law of nature, – they were child’s eyes, like yours, – and I have pressed his hand!” and then he kissed me again.

More than a month had passed, when a letter from Frederick brought us the news that he was engaged to a beautiful and lovable young girl, whom he was sure the whole family would be delighted with. He sent her photograph,6Here Andersen references the Daguerreotype, one of the earliest photographic processes, first published by Daguerre of Paris in 1839, in which the impression was taken upon a silver plate sensitized by iodine, and then developed by exposure to the vapour of mercury. (OED) too, and we all looked at it just so with our eyes, and then with a magnifying-glass; for this is the beauty of those pictures, – that not only can they bear the closest inspection by the sharpest magnifying-glass but that then, and not till then, you get the full likeness. This is what no painter has been able to do, not even the greatest in old times.

“If only that discovery had been made earlier in my time,” said great-grandfather, “then we might now have seen, face to face, the world’s greatest and best men! How good and gentle this young girl looks,” and he gazed long at her through the glass. “Now I know her face, I shall recognize her at once, when she comes in at the door.” But that had very nearly never come to pass; luckily, we at home did not hear of the danger till it had past.

An original illustration of Frederick’s wife on shore from The Riverside Magazine For Young People

The young couple reached England pleasantly and safely, and from there they meant to go by steamer to Copenhagen. They were in sight of land, – the Danish coast, and the white, sandy downs of the west coast of Jutland. There was a heavy sea, that threatened to dash the ship on the shore, and no life-boat could get out to them. Then came the night, dark and dismal; but in the midst of the darkness came a bright blazing rocket from the shore, and shot out far over the ship that was aground. The rocket carried a rope, that fell down on the ship; and thus the connection between those on shore and those at sea was established. And soon, through the heavy, rolling sea, the saving-car7Other versions of the story translate this as some form of a lit rescue buoy, but what exactly the ‘blazing rocket’ and ‘saving-car’ resembled in modern terms is not clear. was being drawn slowly toward the shore: and in it was a young and lovely woman, alive and well; and wonderfully happy was she when her young husband stood by her side on the firm, sandy beach. All on board were saved, and that before it was quite day.

We were sound asleep here in Copenhagen, thinking neither of sorrow nor danger. When we were all assembled for breakfast came a rumor, caused by a telegram, of the wreck of an English steamer on the west coast. We all grew heart-sore and anxious; but within the hour came a telegram from the dear ones, who were saved, – Frederick and his young wife, – who would soon be with us.

All cried; I cried too, and great-grandfather cried, and folded his hands, and – I am sure of it – blessed the present age.

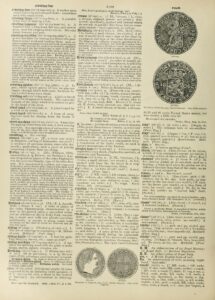

Rix-dollar dictionary definition page.

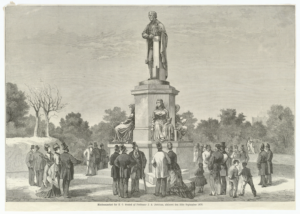

That day great-grandfather gave two hundred rix-dollars8A silver coin and unit of account, current from the late 16th to the mid 19th centuries in various European countries, esp. the Netherlands, the Holy Roman Empire (and subsequently the Austrian Empire), Sweden, Denmark, and Scotland. A rix-dollar usually had a US value of a little over $1.00, so it’s fair to assume great-grandfather’s donation was slightly over $200.00 US dollars. (OED) toward erecting the monument to Hans Christian Örsted.9In 1829, Andersen registered for an examination to receive his honors degree. One of his examiners was Hans Christian Ørsted, the discoverer of electro-magnetism. When he asked Andersen to describe what he knew about the topic, Andersen replied, ‘I don’t even know the word. There is no mention of it in your textbook on chemistry,’ (Bredsdorff 73). After this laughable interaction, Andersen and Ørsted remained life-long friends and pen-pals. The scientist was even ‘[…] the first to appreciate Andersen’s genius as a writer of fairy tales’ in 1835 and predicted the author’s success early on (Bredsdorff 204). The monument alluded to by Andersen here exists in Ørsted Park in central Copenhagen, Denmark, and was inaugurated in 1876 to honor the physicist’s contributions (but its concept was conceived in 1860, making Andersen knowledgeable of the project despite his death prior to the monument’s public reveal). When Frederick came home with his young wife, and heard of it, he said: “That was right, great-grandfather! Now I’ll read for you what Örsted wrote, many, many years ago, about old times and new times!”

“I suppose he was of your opinion,” said great-grandfather.

“Yes, that you may be sure of,” said Frederick; “and so are you, for you have given something to his monument!”

“The memorial for HC Ørsted by Professor JA Jerichau, unveiled on 25 September 1876″ located in Ørsted Park in central Copenhagen, Denmark.

Source Text:

Andersen, Hans Christian. “Great-Grandfather.” The Riverside Magazine for Young People, vol. 4, no. 44, August 1870, pp. 337-340. https://archive.org/details/sim_riverside-magazine-for-young-people_1870-08_4_44/mode/2up?q=by+hans

References:

Belloc, Elizabeth. “Hans Christian Andersen.” Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review, vol. 41, no. 161, 1952, pp. 55–60. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/30099895.

Bredsdorff, Elias. Hans Christian Andersen: The Story of His Life and Work, 1805-75. C. Scribner’s Sons, 1975.

Dal, Erik. “HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN’S TALES AND AMERICA.” Scandinavian Studies, vol. 40, no. 1, 1968, pp. 1–25. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40916900.

Gøbel, Erik. The Danish Slave Trade and Its Abolition. Brill, 2016.

Spiegel, Taru Rauha and Kristi Planck Johnson. “The Spirit of Hans Christian Andersen

in the United States.” The Bridge, vol. 37, no. 2, Article 10, 2014. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol37/iss2/10.

Image References:

Hallager, Thora. “Hans Christian Andersen.” Photograph. Great Norwegian Encyclopedia, 1867. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Als, Peder, and Gotthard Wilhelm Åkerfelt. “Portrait of Christian VII, King of Denmark and Norway.” Oil painting on canvas, 1776-1778. The State Heritage Museum. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons,

Original illustration. “Great-Grandfather.” The Riverside Magazine for Young People, vol. 4, no. 44, August 1870, pp. 339. Courtesy Internet Archive.

Whitney, William Dwight, and Benjamin E. Smith. “Rigsdaler of Denmark, 1854, silver. – British Museum. (Size of Original).” The Century dictionary and cyclopedia; a work of universal reference in all departments of knowledge, with a new atlas of the world…, New York: The Century Co., 1897, pp. 5198. Courtesy Internet Archive.

“The memorial for HC Ørsted by Professor JA Jerichau, unveiled on 25 September 1876.” The Royal Library of Denmark’s Digital Collections, Picture Collections. Courtesy The Royal Library.