HEADNOTE

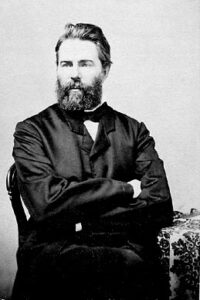

One of the most celebrated authors of the American Renaissance period, Herman Melville was a prolific novelist, short story writer and poet from New York City. His experiences during his five-year career working on various merchant vessels inspired Melville to author several sea-adventure novels such as Typee (1846), Omoo (1847), the posthumously published Billy Budd, Sailor (1924), as well as his magnum opus: a great American classic, Moby Dick (1851). However, in the summer of 1853, Melville, deeply in debt, wrote several essays and short stories for various periodical publications (Maxwell). He published three of these short stories in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine; one appeared in the June 1854 edition under the title ‘Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs’.

In this excerpt, Herman Melville comments on the destitute conditions of the prototypical poor rural American household. He takes aim at the denialist sentiment shown by upper-class citizens who patronize their impoverished countrymen rather than acknowledging the brutal reality of their lives. In the opening conversation of ‘Picture First’, an unnamed narrator listens to his friend, Blandmour, describe the ameliorating charities nature bestows on the poor, from which ‘out of their very poverty, [the poor] extract comfort’ (Melville, 95). Blandmour lists off several practical uses of nature’s snowfall, such as its soil-enriching qualities which garner it the moniker of ‘Poor Man’s Manure’, as well as its medicinal utility as ‘Poor Man’s Eye-water’. The eponymous ‘Poor Man’s Pudding’ is especially praised by Blandmour, who claims it is just as tasteful as a rich man’s meal. After the narrator eventually tries the highly promoted meal within the ramshackle cabin of poor Americans, Martha and William Coulter, the narrator recognises the contradiction between the term and the reality he heard in the euphemistic, romanticized reality described by Blandmour.

Melville formats his short story as a diptych, separating two individual narratives as ‘Picture First’ and ‘Picture Second’, both of which connect and resemble each other in structure, as well as represent a dichotomy between American and British poverty. The word diptych derives from the Latin word dyptychum, which signified something folded in two. Christians within the Roman Empire used diptychs often for sacramental purposes, with each side depicting sacred scenes that shared a connection. Later use of the diptych ornament during the Renaissance era featured provocative contrasts ‘between sin and crucifixion, crucifixion and judgement, prosperity and ruin, glamour and decay’ (Duban, 276).

As author James Duban remarks of Melville’s incorporation of this structure, ‘In using the diptych form, then, Melville was drawing on a well-established pictorial tradition, but he bent that tradition to serve the ends of plaintive social commentary’ (Duban, 277). Melville uniquely experimented with diptychs during this period, with the two other short stories he sent to Harper’s New Monthly Magazine following this format. One of these included a similar commentary on British/American society called ‘Paradise of Bachelors, Tartarus of Maids’.

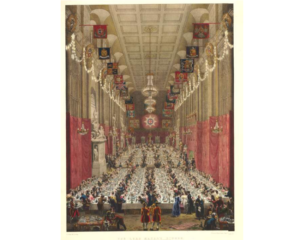

‘Picture Second’ presents the juxtaposed, other narrative of Melville’s diptych. Dubbed, ‘Rich Man’s Crumbs’, ‘Picture Second’ shares a connection with ‘Picture First’ in that the narrator once again finds himself facing the gloomy reality of the impoverished. However, in this episode, the narrator is in a post-Waterloo England, where he observes the beggar lives of the inner-city paupers of London. The narrator accompanies a uniformed ‘civic subordinate’ to the aftermath of the grand Guildhall Banquet feast hosted by the Lord Mayor of London. While the elegant feast was attended by various dukes, princes and kings of European aristocracies, the narrator bewilderedly witnesses the subsequent ‘charity’ of the Lord Mayor of London, wherein the struggling paupers gather en masse to receive what they can of the half-eaten scraps left over from the previous night.

Melville highlights various similarities and differences between rural poor Americans and urban London paupers. While he draws distinctions between how the poor of both societies view charity from others, the upper-class in both the US and England, in this narrative’s depiction, share the same denialist view of the poor’s material conditions. How the poor respond to possible charity differs in the two settings, however. In ‘Picture First’, the Coulter family rejects any charitable offering from the narrator, including favors as miniscule as helping set the table. However, in ‘Picture Second’, the Londoners at the Guildhall revel in their state-sponsored giveaway of high-end leftovers. Both Blandmour and the narrator’s guide from ‘Picture Second’ feign ignorance to the absurdity of the twisted realities they describe, wherein snow and half-eaten cake are indicative of the poor not suffering as much as one would think.

The themes Melville constructs in ‘Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs’ represent transatlanticism by commenting vividly on shared political dynamics and differences between American and British culture. Melville’s narrator attributes the divide to ‘Those peculiar social sensibilities nourished by our own peculiar political principles’ (Melville, 98). In other words, Americans in the world of Melville’s story are programmed to reject charity, despite how grave their conditions may be, as a result of the nation’s republic being founded through revolution and emphasizing individualism. Moreover, while the US upper classes bear no risk from embracing this sentiment and crediting their rationale to the ‘American Dream’, the poor buying into this ideology only serves to possibly worsen their material conditions.

Editorial work on this entry by Declan Whelan

From ‘Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs’ in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine (1854)

Herman Melville, ca. 1860. Photograph

PICTURE FIRST.

POOR MAN’S PUDDING.

“You see,” said poet Blandmour, enthusiastically – as some forty years ago we walked along the road in a soft, moist snow-fall, toward the end of March – “you see, my friend, that blessed almoner1A person who gives alms, such as money or food, to the poor. (OED), Nature, is in all things beneficent; and not only so, but considerate in her charities, as any discreet human philanthropist might be. This snow, now, which seems so unseasonable, is in fact just what a poor husbandman needs. Rightly is this soft March snow, falling just before seed-time, rightly is it called ‘Poor Man’s Manure.’ Distilling from kind heaven upon the soil, by a gentle penetration it nourishes every clod, ridge, and furrow. To the poor farmer it is as good as the rich farmer’s farm-yard enrichments. And the poor man has no trouble to spread it, while the rich man has to spread his.”

“Perhaps so,” said I, without equal enthusiasm, brushing some of the damp flakes from my chest. “It may be as you say, dear Blandmour. But tell me, how is it that the wind drives yonder drifts of ‘Poor Man’s Manure’ off poor Coulter’s two-acre patch here, and piles it up yonder on rich Squire Teamster’s twenty-acre field?”

“Ah! to be sure – yes – well; Coulter’s field, I suppose, is sufficiently moist without further moistenings. Enough is as good as a feast, you know.”

“Yes,” replied I, “of this sort of damp fare,” shaking another shower of the damp flakes from my person. “But tell me, this warm spring-snow may answer very well, as you say; but how is it with the cold snows of the long, long winters here?”

“Why, do you not remember the words of the Psalmist?2The Book of Psalms from the Old Testament: A five book collection of one hundred and fifty poems singing praise to God. Attributed to several known, and unknown, authors. – ‘The Lord giveth snow like wool;’ meaning not only that snow is white as wool, but warm, too, as wool. For the only reason, as I take it, that wool is comfortable, is because air is entangled, and therefore warmed among its fibres. Just so, then, take the temperature of a December field when covered with this snow-fleece, and you will no doubt find it several degrees above that of the air. So, you see, the winter’s snow itself is beneficent; under the pretense of frost – a sort of gruff philanthropist – actually warming the earth, which afterward is to be fertilizingly moistened by these gentle flakes of March.”

“I like to hear you talk, dear Blandmour; and, guided by your benevolent heart, can only wish to poor Coulter plenty of this ‘Poor Man’s Manure.’

“But that is not all,” said Blandmour, eagerly. “Did you never hear of the ‘Poor man’s Eye-water?’”

“Never.”

“Take this soft march snow, melt it, and bottle it. It keeps pure as alcohol. The very best thing in the world for weak eyes. I have a whole demijohn3A large bottle with a bulging body and a narrow neck, usually cased in wicker. (OED) of it myself. But the poorest man, afflicted in his eyes, can freely help himself to this same all-bountiful remedy. Now, what a kind provision is that!”

“Then ‘Poor Man’s Manure’ is ‘Poor Man’s Eye-water’ too?”

“Exactly. And what could be more economically contrived? One thing answering two ends – ends so very distinct.”

“Very distinct, indeed.”

“Ah! that is your way. Making sport of earnest. But never mind. We have been talking of snow; but common rain-water – such as falls all the year round – is still more kindly. Not to speak of its known fertilizing quality as to fields, consider it in one of its minor lights. Pray, did you ever hear of a ‘Poor Man’s Egg?’”

“Never. What is that, now?”

“Why, in making some culinary preparations of meal and flour, where eggs are recommended in the receipt-book, a substitute for the eggs may be had in a cup of cold rain-water, which acts as leaven. And so a cup of cold rain-water thus used is called by housewives a ‘Poor Man’s Egg.’ And many rich men’s housekeepers sometimes use it.”

“But only when they are out of hen’s eggs, I presume, dear Blandmour. But your talk is – I sincerely say it – most agreeable to me. Talk on.”

“Then there’s ‘Poor Man’s Plaster’ for wounds and other bodily harms; an alleviative and curative, compounded of simple, natural things; and so, being very cheap, is accessible to the poorest of sufferers. Rich men often use ‘Poor Man’s Plaster.’”

“But not without the judicious advice of a fee’d physician, dear Blandmour.”

“Doubtless, they first consult the physician; but that may be an unnecessary precaution.”

“Perhaps so. I do not gainsay it. Go on.”

“Well, then, did you ever eat of a ‘Poor Man’s Pudding?’”

“I never so much as head of it before.”

“Indeed! Well, now you shall eat of one; and you shall eat it, too, as made, unprompted, by a poor man’s wife, and you shall eat it at a poor man’s table, and in a poor man’s house. Come now, and if after this eating, you do not say that a ‘Poor Man’s Pudding’ is as relishable as a rich man’s, I will give up the point altogether; which briefly is: that, through kind Nature, the poor, out of their very poverty, extract comfort.”

Not to narrate any more of our conversations upon this subject (for we had several – I being at that time the guest of Blandmour in the country, for the benefit of my health), suffice it that, acting upon Blandmour’s hint, I introduced myself into Coulter’s house on a wet Monday noon (for the snow had thawed), under the innocent pretense of craving a pedestrian’s rest and refreshment for an hour or two.

I was greeted, not without much embarrassment – owing, I suppose, to my dress – but still with unaffected and honest kindness. Dame Coulter was just leaving the wash-tub to get ready her one o’clock meal against her good man’s return from a deep wood about a mile distant among the hills, where he was chopping by day’s-work – seventy-five cents per day and found himself. The washing being done outside the main building, under an infirm-looking old shed, the dame stood upon a half-rotten, soaked board to protect her feet, as well as might be, from the penetrating damp of the bare ground; hence she looked pale and chill. But her paleness had still another and more secret cause – the paleness of a mother to be. A quiet, fathomless heart-trouble, too, couched beneath the mild, resigned blue of her soft and wife-like eye. But she smiled upon me, as apologizing for the unavoidable disorder of a Monday and a washing-day, and, conducting me into kitchen, set me down in the best seat it had – an old-fashioned chair of an enfeebled4Made weak, lacking strength (OED) constitution.

I thanked her; and sat rubbing my hands before the ineffectual low fire, and – unobservantly as I could – glancing now and then about the room, while the good woman, throwing on more sticks, said she was sorry the room was no warmer. Something more she said, too – not repiningly5 In a discontent manner (OED), however – of the fuel, as old and damp; picked-up sticks in Squire Teamster’s forest, where her husband was chopping the sappy logs of the living tree for the Squire’s fires. It needed not her remark, whatever it was, to convince me of the inferior quality of the sticks; some being quite mossy and toad-stooled6Expanded or increased rapidly; Typically refers to fungi. (OED) with long lying bedded among the accumulated dead leaves of many autumns. They made a sad hissing, and vain spluttering enough.

“You must rest yourself here till dinner-time, at least,” said the dame; “what I have you are heartily welcome to.”

I thanked her again, and begged her not to heed my presence in the least, but go on with her usual affairs.”

The Lord Mayor of London’s Guildhall Banquet, 1829. Melville would witness the feast’s parade procession in the fall of 1849.

I was struck by the aspect of the room. The house was old, and constitutionally damp. The window-sills had beads of exuded dampness upon them. The shriveled sashes shook in their frames, and the green panes of glass were clouded with the long thaw. On some little errand the dame passed into an adjoining chamber, leaving the door partly open. The floor of that room was carpetless, as the kitchen’s was. Nothing but bare necessaries were about me; and those not of the best sort. Not a print on the wall; but an old volume of Doddridge7Philip Doddridge (1702 – 1751); Famed English non-conformist pastor and hymn-writer. His published work, The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul, was translated into seven languages. lay on the smoked chimney-shelf.

“You must have walked a long way, sir; you sigh so with weariness.”

“No, I am not nigh so weary as yourself, I dare say.”

“Oh, but I am accustomed to that; you are not, I should think,” and her soft, sad blue eye ran over my dress. “But I must sweep these shavings away; husband made him a new ax-helve this morning before sunrise, and I have been so busy washing, that I have had no time to clear up. But now they are just the thing I want for the fire. They’d be much better though, were they not so green.”

Now if Blandmour were here, thought I to myself, he would call those green shavings “Poor Man’s Matches,” or “Poor Man’s Tinder,” or some pleasant name of that sort.

“I do not know,” said the good woman, turning round to me again – as she stirred among her pots on the smoky fire – “I do not know how you will like our pudding. It is only rice, milk, and salt boiled together.”

“Ah, what they call ‘Poor Man’s Pudding,’ I suppose you mean.”

A quick flush, half resentful, passed over her face.

“We do not call it so, sir,” she said, and was silent.

Upbraiding8To address, reprimand, or censure a person. (OED) myself for my inadvertence, I could not but again think to myself what Blandmour would have said, had he heard those words and seen that flush.

At last a slow, heavy footfall was heard; then a scraping at the door, and another voice said, “Come, wife; come, come – I must be back again in a jif – if you say I must take all my meals at home, you must be speedy; because the Squire – Good-day, sir,” he exclaimed, now first catching sight of me as he entered the room. He turned toward his wife, inquiringly, and stood stock-still, while the moisture oozed from his patched boots to the floor.

“This gentleman stops here awhile to rest and refresh: he will take dinner with us, too. All will be ready now in a trice: so sit down on the bench, husband, and be patient, I pray. You see, sir,” she continued, turning to me, “William there wants, of mornings, to carry a cold meal into the woods with him, to save the long one-o’clock walk across the fields to and fro. But I won’t let him. A warm dinner is more than pay for the long walk.”

“I don’t know about that,” said William, shaking his head. “I have often debated in my mind whether it really paid. There’s not much odds, either way, between a wet walk after hard work, and a wet dinner before it. But I like to oblige a good wife like Martha. And you know, sir, that women will have their whimseys9Playful, or humorous, behavior (OED).”

“I wish they all had as kind whimseys as your wife has,” said I.

“Well, I’ve heard that some women ain’t all maple-sugar; but, content with dear Martha, I don’t know much about others.”

“You find rare wisdom in the woods,” mused I.

“Now, husband, if you ain’t too tired, just lend a hand to draw the table out.”

“Nay,” said I; “let him rest, and let me help.”

“No,” said William, rising.

“Sit still,” said his wife to me.

The table set, in due time we all found ourselves with plates before us.

“You see what we have,” said Coulter – “salt pork, rye-bread, and pudding. Let me help you. I got this pork of the Squire; some of his last year’s pork, which he let me have on account. It isn’t quite so sweet as this year’s would be; but I find it hearty enough to work on, and that’s all I eat for. Only let the rheumatiz10 A disease caused by an abnormal production or flow of mucus dripping from the nose or eyes. (OED) and other sicknesses keep clear of me, and I ask no favors or favors from any. But you don’t eat of the pork!”

“I see,” said the wife, gently and gravely. “that gentleman knows the difference between this year’s and last year’s pork. But perhaps he will like he pudding.”

I summoned up all my self-control, and smilingly assented to the proposition of the pudding, without by my looks casting any reflections upon the pork. But, to tell the truth, it was quite impossible for me (not being ravenous, but only a little hungry at the time) to eat of the latter. It had a yellowish crust all round it, and was rather rankish11Somewhat offensively strong, especially in taste or smell (OED), I thought, to the taste. I observed, too, that the dame did not eat of it, though she suffered some to be put on her plate, and pretended to be busy with it when Coulter looked that way. But she ate of the rye-bread, and so did I.

“Now, then, for the pudding,” said Coulter. “Quick, wife; the Squire sits in his sitting-room window, looking far out across the fields. His time-piece is true.”

“He don’t play the spy on you, does he?” said I.

“Oh, no! – I don’t say that. He’s a good-enough man. He gives me work. But he’s particular. Wife, help the gentleman. You see, sir, if I lose the Squire’s work, what will become of –” and, with a look for which I honored humanity, with sly significance he glanced toward his wife; then, a little changing his voice, instantly continued – “that fine horse I am going to buy.”

“I guess,” said the dame, with a strange, subdued sort of inefficient pleasantry – “I guess that fine horse you sometimes so merrily dream of will long stay in the Squire’s stall. But sometimes his man gives me a Sunday ride.”

“A Sunday ride!” said I.

“You see,” resumed Coulter, “wife loves to go to church; but the nighest is four miles off, over yon snowy hills. So she can’t walk it; and I can’t carry her in my arms, though I have carried her up-stairs before now. But, as she says, the Squire’s man sometimes gives her a lift on the road; and for this cause it is that I speak of a horse I am going to have one of these fine sunny days. And already, before having it, I have christened it ‘Martha.’ But what am I about? Come, come, wife! the pudding! Help the gentleman, do! The Squire! the Squire! – think of the Squire! and help round the pudding. There, one – two – three mouthfuls must do me. Good-by, wife. Good-by, sir. I’m off.”

And, snatching his soaked hat, the noble Poor Man hurriedly went out into the soak and the mire.

I suppose now, thinks I to myself, that Blandmour would poetically say, He goes to take a Poor man’s saunter.

“You have a fine husband,” said I to the woman, as we were now left together.

“William loves me this day as on the wedding-day, sir. Some hasty words, but never a harsh one. I wish I were better and stronger for his sake. And, oh! sir, both for his sake and mine” (and the soft, blue, beautiful eyes turned into two well-springs), “how I wish little William and Martha lived – it is so lonely-like now. William named after him, and Martha for me.”

When a companion’s heart of itself overflows, the best one can do is to do nothing. I sat looking down on my as yet untasted pudding.

“You should have seen little William, sir. Such a bright, manly boy, only six years old – cold, cold now!”

Plunging my spoon into the pudding, I forced some into my mouth to stop it.

“And little Martha – Oh! sir, she was the beauty! Bitter, bitter! but needs must be borne.”

The mouthful of pudding now touched my palate. and touched it with a mouldy, briny taste. He rice, I knew, was of that damaged sort sold cheap; and the salt from the last year’s pork barrel.

“Ah, sir, if those little ones yet to enter the world were the same little ones which so sadly have left it; returning friends, not strangers, strangers, always strangers! Yet does a mother soon learn to love them; for certain, sir, they come from where the others have gone. Don’t you believe that, sir? Yes, I know all good people must. But, still, still – and I fear it is wicked, and very black-hearted, too – still, strive how I may to cheer me with thinking of little William and Martha in heaven, and with reading Dr. Doddridge there – still, still does dark grief leak in, just like the rain through our roof. I am left so lonesome now; day after day, all the day long, dear William is gone; and all the damp day long grief drizzles and drizzles down on my soul. But I pray to God to forgive me for this; and for the rest, manage it as well as I may.”

Bitter and mouldy is the “Poor Man’s Pudding,” groaned I to myself, half choked with but one little mouthful of it, which would hardly go down.

I could stay no longer to hear of sorrows for which the sincerest sympathies could give no adequate relief; of a fond persuasion, to which there could be furnished no further proof than already was had – a persuasion, too, of that sort which much speaking is sure more or less to mar12To damage, spoil or ruin an enterprise, intention, emotion, etc. (OED); of causeless self-upbraidings, which no expostulations could have dispelled. I offered no pay for hospitalities gratuitous and honorable as those of a prince. I knew that such offerings would have been more than declined; charity resented.

The native American poor never lose their delicacy or pride; hence, though unreduced to the physical degradation of the European pauper13A person in poverty who receives relief under the provisions of the English Poor Laws or of various public charities. (OED), they yet suffer more in mind than the poor of any other people in the world. Those peculiar social sensibilities nourished by our own peculiar political principles, while they enhance the true dignity of a prosperous American, do but minister to the added wretchedness of the unfortunate; first, by prohibiting their acceptance of what little random relief charity may offer; and, second, by furnishing them with the keenest appreciation of the smarting distinction between their ideal of universal equality and their grindstone experience of the practical misery and infamy of poverty – a misery and infamy which is, ever has been, and ever will be, precisely the same in India, England, and America.

Under pretense that my journey called me forthwith, I bade14Having uttered a greeting or farewell to a person(s). (OED) the dame good-by; shook her cold hand; looked my last into her blue, resigned eye, and went out into the wet. But cheerless as it was, and damp, damp, damp – the heavy atmosphere charged with all sorts of incipiencies15A state or process of beginning to exist or becoming apparent. (OED) – I yet became conscious, by the suddenness of the contrast, that the house air I had quitted was laden down with that peculiar deleterious16Having an adverse or harmful effect on the condition of a person, society, etc. (OED) quality, the height of which – insufferable to some visitants – will be found in a poor-house ward.

This ill-ventilation in winter of the rooms of the poor – a thing, too, so stubbornly persisted in – is usually charged upon them as their disgraceful neglect of the most simple means to health. But the instinct of the poor is wiser than we think. The air which ventilates, likewise cools. And to any shiverer, ill-ventilated warmth is better than well-ventilated cold. Of all the preposterous assumptions of humanity over humanity, nothing exceeds most of the criticisms made on the habits of the poor by the well-housed, well-warmed, and well-fed.

“Blandmour,” said I that evening, as after tea I sat on his comfortable sofa, before a blazing fire, with one of his two ruddy17Of a person: red in the face from blushing, exertion, heat, etc. (OED) little children on my knee, “you are not what may rightly be called a rich man; you have fair competence; no more. Is it so? Well then, I do not include you, when I say, that if ever a Rich Man speaks prosperously to me of a Poor Man, I shall set it down as – I won’t mention the word.”

Source Text:

Melville, Herman. ‘Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs’, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 49.9 (June 1854), 95-98. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b000541556&view=page&seq=111&skin=2021&q1=poor%20man%27s

References:

‘Psalms’. Encyclopedia Britannica, 14 Sep. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Psalms

Duban, James. ‘Transatlantic Counterparts: The Diptych and Social Inquiry in Melville’s “Poor Man’s Pudding and Rich Man’s Crumbs”.’ The New England Quarterly, 66.2 (1993), 274–86.

Jenkins, Daniel T. ‘Congregationalism’. Encyclopedia Britannica, 9 Apr. 2021, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Congregationalism.

Maxwell, D.E.S.. ‘Herman Melville’. Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Herman-Melville

Image References:

Herman Melville. , ca. 1860. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004672065/.

The Lord Mayor’s Dinner, 1829. Print. Interior of the Guildhall looking towards the top table during the 1829 Lord Mayor’s dinner. 1829 Lithograph, hand-coloured https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/350155001