Domestic Harmony, the Ghost of Empathy, and the Crux of Scrooge’s Christmas Conversion by Rachel E. Johnston

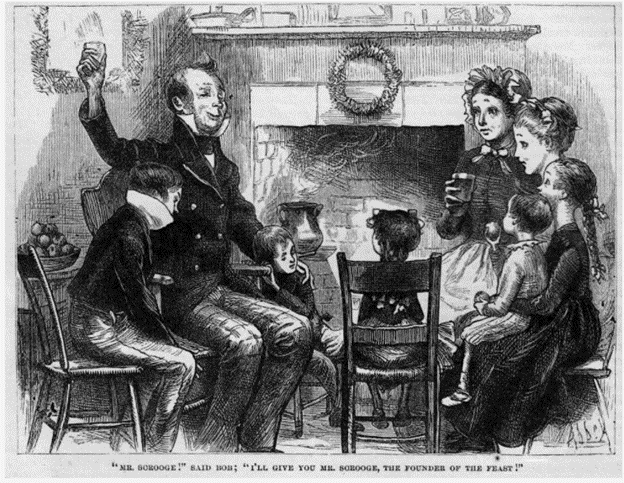

Illustration by E. A. Abbey. Harper and Brothers American Household Edition (1876) of Charles Dickens’ Christmas Stories, image for A Christmas Carol, 28. Courtesy Phillip Allignham and Victorian Web Foundation.

In this memorable domestic scene of Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, cheerful optimist Bob Cratchit toasts his miserly employer, his incorrigible foil Ebenezer Scrooge. The text surrounding the caption of this delightful illustration by E.A. Abbey (which appeared in the Harper and Brothers American Household Edition of Dickens’s Christmas Stories in 1876) detailed Scrooge’s adventures with the second spirit, The Ghost of Christmas Present, and marked Scrooge’s turning point from greedy and selfish to generous and sympathetic. Significantly, this scene is the first of the ghostly visions that Scrooge sought to change when he awakened from his adventures.

In the text of A Christmas Carol, the events leading up to the above illustration began with the Third Stave and the entrance of the Ghost of Christmas Present, a giant whose green robe was open at the chest to mirror his “kind, generous, hearty nature” (59-60). This spirit had a “sympathy with all poor men, that led him straight to Scrooge’s clerk’s” (60). Here “on the threshold of the door the Spirit smiled, and stopped to bless Bob Cratchit’s dwelling with the sprinkling of his torch” (60). Dickens broke the fourth wall and announced an aside to the reader: “Think of that! Bob had but fifteen ‘Bob’ a-week himself; he pocketed on Saturdays but fifteen copies of his Christian name; and yet the Ghost of Christmas Present blessed his four-roomed house!” (60). This punny description of Bob’s poverty not only underlined the charitable propensities held by the embodiment of “the Christmas spirit,” the Ghost of Christmas Present, but also served to illustrate for Scrooge the state of Bob Cratchit’s impoverished domestic situation. By forcing Scrooge to see where and how his fifteen “Bob” a week was spent, and how very short it fell in the upkeep of a large family, this scene became the turning-point in Scrooge’s ability to empathize with others.

Dickens revealed more of the Cratchits’ financial struggles as Scrooge and the second spirit observed the clothes of the family, which artist E. A. Abbey thoughtfully rendered in this illustration. Here we see Mrs. Cratchit, “dressed out but poorly in a twice-turned gown, but brave in ribbons, which are cheap and make a goodly show for sixpence,” “Belinda Cratchit, second of her daughters, also brave in ribbons,” and Master Peter Cratchit in a “monstrous shirt collar (Bob’s private property, conferred upon his son and heir in honour of the day)” (60). Then “in came little Bob, the father, with … his threadbare clothes darned up and brushed, to look seasonable” (61). And at last, high on Bob’s shoulder rode the crux of Scrooge’s nearing conversion, Tiny Tim. Bearing his little crutch and with “his limbs supported by an iron frame!” Tim considered himself to be a reminder to morning churchgoers and now Scrooge of “who made lame beggars walk, and blind men see” (62).

Scrooge and Christmas Present watched the Cratchits through their scanty Christmas goose, small but festive pudding, and yet through the lively conversation, saw that the Cratchits “were happy, grateful, pleased with one another, and contented with the time” (68). After dinner, the Cratchits gathered around the fire to eat apples and oranges, roast chestnuts, but also to taste the Christmas gin punch. Bob served the gin punch into the only three glasses the Cratchits’ owned: “two tumblers, and a custard-cup without a handle” (65) and proposed a toast: “‘A Merry Christmas to us all, my dears. God bless us!’ Which all the family re-echoed. ‘God bless us every one!’ said Tiny Tim, the last of all.” Tiny Tim “sat very close to his father’s side upon his little stool. Bob held his withered little hand in his, as if he loved the child, and wished to keep him by his side, and dreaded that he might be taken from him” (65). Similarly, or sympathetically, Scrooge voiced his fear that Tiny Tim could die, revealing the turning point in his Christmas Eve transformation.“[W]ith an interest he had never felt before,” Scrooge pleaded to his Christmas Present guide: “tell me if Tiny Tim will live” (65). But the Ghost replied: “I see a vacant seat…in the poor chimney-corner, and a crutch without an owner, carefully preserved… If he be like to die, he had better do it, and decrease the surplus population” (65-66). Here Scrooge showed his first remorse but also a new, deep sympathy with others as he “was overcome with [both] penitence and grief” (66).

The Ghost continued his harangue, further pressing Scrooge to understand the wrongs he had committed in the name of economy, demanding of Scrooge to “forbear that wicked cant until you have discovered What the surplus is, and Where it is. Will you decide what men shall live, what men shall die? It may be, that in the sight of Heaven, you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions like this poor man’s child” (66). It is this moment that the illustration above captured the action inside the Cratchits’ house, just as Scrooge himself might have viewed it. On hearing his own name, Scrooge raised his eyes to see Bob Cratchit’s toast to him: “Mr. Scrooge! I’ll give you Mr. Scrooge, the Founder of the Feast!” (66).

How tumultuous the grief and guilt brought on by the Ghost’s remonstrance must have felt with the added shame of seeing and hearing his wronged employee’s open-hearted toast! And this was not all—a sound thrashing by the good Mrs. Cratchit followed: “The Founder of the Feast indeed!… I wish I had him here. I’d give him a piece of my mind to feast upon, and I hope he’d have a good appetite for it” (66). The pleasure evident in the illustrated domestic scene was dampened in a blink, and Bob held calmly to his toast, reminding Mrs. Cratchit and the children of the spirit of the holiday season—one of forgiveness, charity, and goodwill towards men: Christmas Day. Still angry, Mrs. Cratchit honors the values of the season: “I’ll drink his health for your sake and the Day’s…not for his” (66-67). As Dickens explained “Scrooge was the Ogre of the family. The mention of his name cast a dark shadow on the party, which was not dispelled for full five minutes” but, after this darkness had passed, the family was “ten times merrier than before, from the mere relief of Scrooge the Baleful being done with” (67).

Thus ended the critical transitional scene for Scrooge. The once-again festive Cratchit family circle “faded, and looked happier yet” and “Scrooge had his eye upon them, and especially on Tiny Tim, until the last” (68). Though Scrooge had more to see and more to learn from both the second and third ghosts that Christmas night, this scene was the first one which he attempted to change after awakening on Christmas morning. Unselfishly, he sought to bring the Cratchits more pleasure and nutrition without yet revealing his change of heart. When he awoke after his visitation from the Ghost of Christmas To Be, Scrooge opened the window, discovered he still had time to make a difference, and ordered the prize Christmas goose be sent anonymously to the Cratchits (108). Scrooge was unconcerned that Mrs. Cratchit and the children would likely respond to Bob’s forthcoming toast to him in the same manner as they did during his visit with the Ghost of Christmas Present. This means that the illustration above, a scene both frozen in time and repeated in copies through the media of magazine publishing, would have likely occurred again, unchanged, just as Scrooge had witnessed the night before, but with fuller stomachs and a stocked larder for the Cratchits. As the verbal echoes of Abbey’s striking illustration would suggest, Scrooge allowed himself to remain the villain or ghost haunting the Cratchits’ Christmas for one more day, unwilling to touch or alter the scene above, unwilling to change the vision which led to his redemption.

Source:

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. Barnes and Noble Books, New York. 1994.