HEADNOTE

Rubén Darío was a distinguished Nicaraguan poet best known for his role as the father of modernismo, the Spanish and Latin American modernist movement. Darío is also credited with igniting a renaissance of the literature and poetry of Latin America by giving the writers of this region a new and unique voice and ridding them of the constraining Spanish influence (Neville). Scholars and readers alike have celebrated Darío for his creative and transformative uses of language, which were undoubtedly shaped by his global travel experiences and engagement with various cultures and languages. In fact, there is a record of Darío visiting at least thirty countries across three different continents (Neville). The impact of his travels can be clearly seen in many of his works. The city of Paris as well as many of the French poets of his time were some of Darío’s greatest influences. Because of this cultural affinity, one of Darío’s dreams for modernismo was to popularize Latin American literature in France, and a specific personal goal of his was to publish works in French (Grigsby 721). While Darío spent over a decade in Paris, even prior to its popularity among the expat writers of American modernism, he also spent many years in Argentina. Buenos Aires was the site of publication for many of his early works, and Darío considered the city to be the Latin American equivalent of Paris. His travels and his poetry are part of the reason why he remains a celebrated poet across the globe to this day.

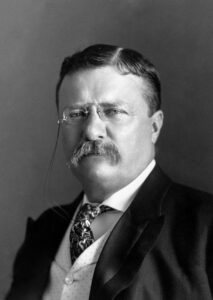

Although Darío’s most well-known works are his poetry collections such as Azul, the following poem, ‘A Roosevelt’, is still an important work in his repertoire. This poem was published in the period following Panama’s independence and the signing of the Hay-Bunau-Varilla treaty, which would lead to the creation of the Panama Canal. In this poem Darío directly addresses Theodore Roosevelt, who was president of the United States from 1901 to 1909. During Roosevelt’s two-term presidency the addition of the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine led to increasing US intervention in Latin American countries. Darío frankly voices his frustrations towards the United States and Roosevelt for the implementation of these policies. At the same time, he expresses pride in Latin America’s Indigenous roots and fear that continued US invasion will threaten this history. Darío’s pride in his homeland stemmed from his romanticisation of Latin America’s pre-colonial and pre-Hispanic past (Ortiz 347), a perspective clearly seen in references to ‘Netzahualcoyotl’, ‘Cuauhtemoc,’ and ‘Tenochtitlan’ in the poem ‘A Roosevelt.’ He also wrote a similar poem titled ‘To Columbus’ in which he lamented Columbus’s arrival to the Americas and remarks that the region would likely have been better had Columbus never interfered (Ortiz 348). Darío was an early critic of American imperialism, and in his work Cantos de vida y esperanza, he ‘formulates a constant critical reflection on the imperial threat of the United States’ (Sanhueza 305, 309). Thus, given what is known about Darío and his works, the English-language translation of his poem ‘A Roosevelt’ aims to capture a combination of Darío’s poetic lyricism and his critical stance toward both US imperialism and Roosevelt himself.

The following translation makes advised linguistic choices to represent the lyrical voice as well as the political opinion of Darío. We have consulted Roque Barcia’s 1902 Spanish-language dictionary Primer Diccionario General Etimológico de la Lengua Española to ensure that the translation is also true to the time period of the original poem. For further details, see the footnotes in the translation.

Editorial work on this entry by Rosa Velazquez.

‘A Roosevelt’ (1907)

Translation of ‘A Roosevelt’ by Rosa Velazquez and Stephanie Peebles Tavera,

In consultation with Ayendy Bonifacio

Author Rubén Darío.

‘A Roosevelt’

Es con voz de la Biblia, o verso de Walt Whitman,

Que habría de llegar hasta tí, Cazador!

Primitivo y moderno, sencillo y complicado,

Con un algo de Washington y cuatro de Nemrod!

Eres los Estados Unidos,

Eres el futuro invasor

De la América ingenua que tiene sangre indígena,

Que aun reza a Jesucristo y aun habla en español.

Eres soberbio y fuerte ejemplar de tu raza;

Eres culto, eres hábil; te opones a Tolstoy.

Y domando caballos, o asesinando tigres,

Eres un Alejandro-Nabucodonosor.

(Eres un Profesor de Energía

Como dicen los locos de hoy.)

Crees que la vida es incendio

Que el progreso es erupcíon;

Que en donde pones la bala

El porvenir pones.

No.

Los Estados Unidos son potentes y grandes.

Cuando ellos se estremecen hay un hondo temblor

Que pasa por las vértebras enormes de los Andes.

Si clamáis se oye como el rugir del león.

Ya Hugo a Grant le dijo: Las estrellas son vuestras.

(Apenas brilla, alzándose, el argentino sol

Y la estrella chilena se levanta…) Sois ricos.

Juntáis al culto de Hércules el culto de Mammón,

Y alumbrando el camino de la fácil conquista,

La Libertad levanta su antorcha en Nueva York.

Mas la América nuestra, que tenía poetas

Desde los viejos tiempo de Netzahualcoyotl,

Que ha guardado las huellas de los pies del gran Baco,

Que el alfabeto pánico en un tiempo aprendió;

Que consultό los astros, que conoció la Atlántida

Cuyo nombre nos llega resonando en Platón,

Que desde los remotos momentos de su vida

Vive de luz, de fuego, de perfume, de amor,

La América del grande Moctezuma, del Inca.

La América fragante de Cristóbal Colón,

La América católica, la America española,

La América en que dijo el noble Guatemoc:

«Yo no estoy en un lecho de rosas»; esa América

Que tiembla de huracanes y que vive de Amor;

Hombres de ojos sajones y alma bárbara, vive.

Y sueña. Y ama, y vibra; y es la hija del Sol.

Tened cuidado: ¡Vive la América Española!

Hay mil cachorros sueltos del León Español

Se necesitaría, Roosevelt, ser por Dios mismo,

El Riflero terrible y el fuerte Cazador,

Para poder tenernos en vuestras férreas garras.

Y puedes contáis con todo, falta un cosa: ¡Dios!

President Roosevelt circa 1904.

‘To Roosevelt’

Translated by Rosa Velazquez & Stephanie Tavera, with consultation from Ayendy Bonifacio

With Biblical voice, or a Walt Whitman verse,

that I should reach you, Hunter!

Primitive and modern, simple and complicated,

With portions of Washington and portions of Nimrod!

You are the United States,

You are the future invader

of a naïve America with indigenous blood,

that in Spanish still prays to Jesus Christ.1This line is a reference to Argentine philosopher Juan Bautista Alberdi’s book, Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina. This text was influential to the creation of the Constitution of Argentina, as many of Alberdi’s ideas were incorporated into the final Constitution. Alberdi juxtaposes Indigenous and European cultures against one another.

You are an arrogant and strong specimen of your race;2Many translators opt for a more literal translation of ‘ejemplar’ in this line by choosing the word ‘example’ for the phrase ‘example of your race.’ However, we have opted for ‘specime’” instead because we believe Darío is saying that Roosevelt is considered a model of his race; he is the typical colonialist. One of the reasons we made this translation choice is because of the usage of ‘ejemplar’ in a 1902 Spanish dictionary, which defines ‘ejemplar’ as ‘a prototype, serving as an example for others who are similar to follow.’ Thus, we feel either ‘specimen’ or ‘model’ most accurately represents this definition in modern language. For the original definition, see Roque Barcia, Primer Diccionario General Etimológico de la Lengua Española (Barcelona: Francisco Seix, 1902), p. 332, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000048708197&view=1up&seq=338.

You are cultured, you are capable;3Even though most translators, including us, opt for ‘cultured’ as the translation of ‘culto’ in this line, it is worth pointing out the operative definition during Darío’s time. The 1902 Spanish dictionary defines ‘culto’ as ‘the application of a pure and correct style.’ In a word: pristine, or perfect mannerisms. Not just cultured in the sense of well-read or educated in a worldly fashion or having good taste, but someone who performs publicly in an elegant way. Meanwhile, ‘hábil’ is often literally translated as ‘skilled,’ but it meant something a little more nuanced during Darío’s time. The 1902 Spanish dictionary defines ‘hábil’ as ‘competent/capable, intelligent, and willing to perform any manner of exercise, office, or ministry.’ This sounds precisely like what Dario means about Roosevelt’s leadership style as president—and is mocking! For the entry on ‘culto’, see: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000048708180&view=1up&seq=1162; for the entry on ‘hábil’, see: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000048708197&view=1up&seq=1091. you oppose Tolstoy.

And taming horses, or killing tigers,

You are an Alexander-Nebuchadnezzar.4This is likely a reference to both Alexander the Great and Nebuchadnezzar II. Alexander the Great (356 BC – 323 BC) was the king of Macedonia. Nebuchadnezzar II (605 BC – 562 BC) was an ancient Babylonian King. Both were celebrated and respected leaders, and both were particularly recognized for their military might.

(You are a Professor of Energy

So say the madmen of today.)

You think that life is a fire.

That progress is explosion.5This couplet was particularly challenging to translate because Darío is using the concept of ‘fire’ and ‘explosion’ metaphorically. Once again, most translators opt for a more literal translation, but it’s worth taking the time to explain what Darío was doing here, poetically. In the 1902 Spanish dictionary, ‘incendio’ is defined as ‘the affections that vehemently heat and agitate the mood such as anger.’ To translate ‘incendio’ as ‘fire’ risks losing its connotation of ‘passion’, but Darío also means an angry kind of passion for possession of something not just a passionate love for life. Meanwhile, ‘erupcíon’ is often literally translated as ‘eruption’, but we chose ‘explosion’ instead to emphasize the violence of ‘incendio’ and the violence of ‘erupcíon.’ Darío is possibly thinking of the medical definition ‘erupcíon’, meaning ‘contagion’, as much as he is thinking of the geological and geographic definitions of ‘erupcíon’, meaning a volcanic eruption as well as a description of population growth. Darío is commenting on the violence of colonization, which is simultaneously contagious, volcanic, and expansive. For the entry on ‘incendio’, see: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433075924948&view=1up&seq=48; for the entry on ‘erupcíon’, see: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000048708197&view=1up&seq=468.

That where you send the bullet,

The future follows.

No.

The United States is powerful and great.

When it shakes, there is a deep tremor

that passes through the enormous vertebras of the Andes.

If you cry it sounds like the roar of a lion.

Hugo has already said to Grant: The stars are ours.

(Just barely shining, the Argentine suns ascends

and the Chilean star rises…) You are rich.

You’ve joined to the cult of Hercules, the cult of Mammon;6Mammon is a Biblical concept often used to denote either wealth or greed.

and illuminating the path to easy conquest,

Liberty raises her torch in New York.

Greater is our America, that had poets

since the age of Netzahualcoyotl,7Netzahualcoyotl was a pre-Hispanic Mexica leader, poet, and scholar. He was of mixed Mexica and Acolhua ancestry. He traveled to Tenochtitlan (the former Mexica capital, which is in present-day Mexico City, and which was ruled by his maternal uncle who was the emperor at the time) after the death of his father. He was educated in the customs of the Mexica people, and he came to be the ruler of the city-state of Texcoco.

that has guarded the footprints of the great Bacchus,

that once learned the panic alphabet,

that consulted the stars who knew Atlantis,

whose name comes to us echoing Plato,

that from the remotest moments of her life,

lives from light, from fire, from perfume, from love,8Most translators use ‘of’ rather than ‘from’ for ‘de” in their translations of ‘A Roosevelt.’ However, we believe that the subject being modified in lines 30-37 is ‘America.’ If the subject of the sentence broken across these lines is ‘America’, then her life is one that emerges ‘from [human] life, from fire, from perfume, from love.’ In other words, it is these things that animate her and the (human) lives that depend on her.

the America of the great Moctezuma, of the Inca.

The fragrant America of Christopher Columbus,

The Catholic America, the Spanish America,

The America in which the noble Cuauhtemoc said:9Cuahtemoc was the last Aztec emperor before the fall of Tenochtitlan, and subsequently, the fall of the Aztec Empire. The city of Tenochtitlan, which is the present-day historic center of Mexico City, was invaded when Hernán Cortés led Spanish forces into a violent siege of the city in 1521.

“I am not in a bed of roses”; that America

which trembles from hurricanes and lives on love;

Men of Saxon eyes and cruel souls, live.

And dreams. And loves, and pulses; and is the daughter of the Sun.

Beware: Long live Spanish America!

There are a thousand Spanish lion cubs on the loose

It would require you, Roosevelt, next to God himself,10Here, we translate ‘ser por Dios mismo’ as ‘next to God himself’ in order to incapsulate the play on words that Darío invokes in this phrase. On the one hand, Darío means ‘next to’ as in ‘alongside’ or ‘besides’, meaning Roosevelt could not colonize Latin America without God by his side ordaining or leading the charge. This reinforces the final line of the poem to mean that God is not by Roosevelt’s side, and therefore, Roosevelt will fail. On the other hand, Darío means ‘next to’ as in ‘in place of God himself’, or acting as God himself, meaning that Roosevelt must consider himself stronger than God in order.

the terrible Rifleman and strong Hunter,

to grasp us in your claws.

And you can count on this, there is one thing missing: God!

Source Text:

Darío, Ruben. ‘A Roosevelt’ [‘To Roosevelt’], Cantos de vida y esperanza: Los cisnes y otras poemas [Songs of Life and Hope: The Swans and Other Poems]. Barcelona: Casa Editorial Maucci, 1907.

References:

Barcia, Roque. Primer Diccionario General Etimológico de la Lengua Española. Barcelona: Francisco Seix, 1902.

Feinstein, Adam. ‘Rubén Darío Meets His Hero.’ The Rimbaud and Verlaine Foundation, 2020, https://www.rimbaudverlaine.org/en/news/ruben-dario-meets-his-hero/.

Grigsby, Carlos F. ‘El fracaso de París: Rubén Darío’s Modernista Campaign in France.’ In The Modern Language Review 114.4, (2019), 720-39.

Monguió, Luis. ‘El Origen de Unos versos de “A Roosevelt.”’ In American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese 38.4 (1945), 424-26.

Neville, Tim. ‘The Inescapable Poet of Nicaragua.’ The New York Times, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/11/27/travel/nicaragua-dario-poet.html#:~:text=Almost%20any%20Spanish%20speaker%20will,wasn’t%20just%20a%20writer.

Ortiz, Roberto José. ‘Aristocratic Rebellion: Ruben Darío and the Creation of Artistic Freedom in the World-System.’ In, Journal of World-Systems Research, 21.2, (2015), Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 339-61.

Sanhueza, Marcelo. ‘Entre imperios: antiimperialismo e hispanoamericanismo en España contemporánea de Rubén Darío.’ In Catedral Tomada Revista de Crítica Literaria Latinoamericana 7.12 (2019), Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 298-337.

Image Citations:

Pach Brothers, “President Roosevelt” Photograph. 1904. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

“Rubén Darío” Photograph. Date unknown. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.