Washington Irving Background and ‘Rural Funerals’ Crux and Purpose

by Devian Poteet-Reed

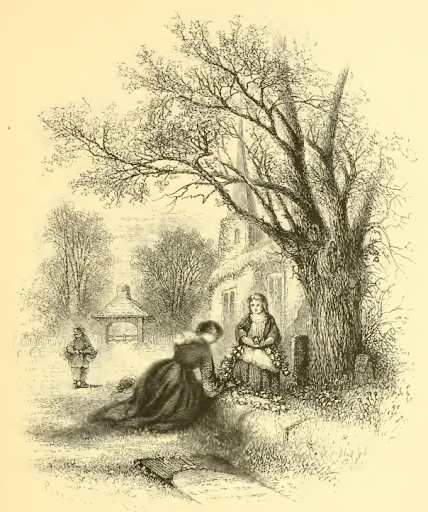

Bellows, Alfred F. ‘Children in the Churchyard.’

Washington Irving, Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Artist’s Edition (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1864), 195. Courtesy HathiTrust.

Washington Irving was a popular short story writer and essayist in the early 19th century, best known for his short story ‘The Legend of Sleepy Hollow’ (1820) and use of romanticism. Irving adopted several pseudonyms throughout his literary career, which granted him an opportunity to self-reflect, self-criticize, and tell the truth. Demonstrating his desire to reflect on the world around him, Washington Irving’s collection of essays and short stories, Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Artist’s Edition, was published under his pseudonym, Geoffrey Crayon. His Sketch Book contained several illustrations and a mix of thirty-four essays and short stories. The collection’s most notable characteristic is how it contrasts the emerging American identity with the already established English identity.

In his essay ‘Rural Funerals’, Irving describes the beauty of traditional burial grounds and rites in rural England. Irving emphasizes an awe for nature as he contemplates the English funeral tradition of adorning the grave by saying, ‘There is certainly something more affecting in these prompt and spontaneous offerings of Nature…the hand strews the flower while the heart is warm, and the tear falls on the grave as affection is binding the osier round the sod’ (64). Irving’s reflections provide a romantic account of the connection between the living, the dead and the natural world, and highlight the association between English and American customs that foreground the funeral.

‘Rural Funerals’ challenged American readers to consider how the beauty of nature is a palpable expression of love that mourners offer up to departed loved ones. Jane Eberwein, a distinguished professor and scholar of American literature at Oakland University asserts in her article ‘Transatlantic Contrasts in Irving’s “Sketch Book’’ that Irving’s Sketch Book is his ‘way of working out his worries about his own prospects and those of his country’ (154). Furthermore, Eberwein explains that Irving’s anxieties centered on his hope for the American imagination to exude a strong connection with nature, similar to the customs of the English Romantics (157). Eberwein’s assertion highlights Irving’s desire for American art, literature, and society to consider the beauty of ancient English customs. In ‘Rural Funerals,’ this desire is apparent when Irving describes the ‘rustic offerings’ of flowers as ‘truly poetical’ (63). Thus, the essay and Sketch Book as a whole should be regarded while studying transatlantic literature and culture, as it calls to mind the American longing to adopt the English morale of honoring the dead.

‘Children in the Churchyard’ Background and Description

The illustration ‘Children in the Churchyard’ by Alfred F. Bellows appeared in Washington Irving’s Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Artist’s Edition. The Artist’s Edition was a special edition that showcased illustrations by various artists that complemented Irving’s writings. ‘Children in the Churchyard’, a wood engraving, appeared alongside the short essay ‘Rural Funerals’.

Showcasing a traditional English Regency practice, the illustration displays a woman wearing a Romantic Era dress, kneeling as she adorns the grave of a departed loved one with a floral wreath. Accompanying the woman are two children: one girl and one boy. The young girl offers succor to the woman, while the little boy seems to be playing, or is perhaps gathering sticks, in the background. The graveyard is connected to a church: viewers can see its large windows, thatched roof, and spire reaching toward the firmament. Various trees form a rural landscape, bending and offering shelter for the faithful departed and visitors. The contrast between the churchyard, the natural world, and the human subjects is eminent and suggests an intimate, or even transcendental, connection.

Memento Mori: The Grave as a Reminder of Mortality

Cultural attitudes towards death become apparent when juxtaposed with their burial rites and grounds. Early American cemeteries did not reflect an optimistic position towards death; instead, they reflected a mere necessity to bury the dead. The first American cemeteries were often crowded, and visitors only entered the grounds for funerals, otherwise avoiding the location. The cemetery was not considered a place for solace or meditation. This ideology began to shift during the American ‘Rural Cemetery’ movement of the mid-nineteenth century, which proposed burial grounds within English-like landscapes and emphasized the Romantic vision expressed in Irving’s ‘Rural Funerals.’

Stanley French, in his article ‘The Cemetery as Cultural Institution: The Establishment of Mount Auburn and the “Rural Cemetery” Movement’, discusses how the ‘burial place [was] designed not only to be a decent place of interment, but to serve as a cultural institution as well’ (38). Prior to this movement, America was documented as a ‘cultural wasteland’ in connection to early graveyard customs (French 37). Clearly, there is a powerful link between a culture’s identity and their burial traditions. French contends that ‘the fullness of nature in the rural cemetery…enable[s] people to see death in perspective so that they might realize that…the circle of creation and destruction is eternal’ (47). To French, there is nothing more ‘natural’ than Nature and Death.

This in mind, it becomes appropriate for the cemetery to foster an ongoing conversation between the living and the dead by positioning itself within the natural world. The Latin phrase memento mori, meaning ‘remember you must die,’ should be considered when meditating on the grave. Rather than regarding it as a passing utility, the grave must be a place that inspires beauty and virtue for it provides a prominent reminder of one’s own mortality.

Adorning the Grave as a Rite of Poetical Devotion

What is the connection between poetry, devotion, nature and the grave? Put simply, poetry is a literary form that is often adopted to express deep emotion or to emphasize an idea. The poet is regarded as a master of words and uses language to participate in the act of creation. The poet offers verse after verse, awakening others to the sublime. Similarly, Irving says of a husband who visits and adorns his wife’s grave that ‘he was twining a fresh chaplet for the grave of his mistress…fulfilling one of the most fanciful rites of poetical devotion, and that he was practically a poet’ (Irving 67). Irving’s metaphor provides an understanding that just as the poet adorns the world with words, the living fulfill the rite of devotion with adoration for the dead.

The practical connection between poetry and death is apparent when one considers that in both past and present-day funerals, mourners often recite and/or present elegies, songs, and psalms. In his essay, Irving includes an excerpt from ‘The Dirge of Jephthah’s Daughter: Sung by the Virgins’ by Robert Herrick, an English poet and Anglican cleric who was beloved in the 17th century. The poem is a dirge, a song of mourning, sung by a group of virgins to Jephthah’s daughter, who was sacrificed by her father as a vow to God in the Book of Judges. Displaying themes of sacrifice and devotion, the virgins promise to honor the life of Jephthah’s daughter through their own while decorating her grave with flowers. This scene is a perfect illustration of the living honoring the lives of those who have gone before them through the mode of Nature. The women lament:

Thus, thus, and thus, we compass round

Thy harmless and unhaunted ground;

And as we sing thy dirge, we will

The daffadil,

And other flowers, lay upon

The altar of our love, thy stone. (qtd. in Irving)

Just as the women lay flowers upon what they deem an ‘altar of [their] love,’ the daughter’s headstone, so too should modern mourners have a sacred altar to adorn. Whether a slanted bevel marker surrounded by poppies, an upright marble stone in the shape of an angel, or a simple red rosebush beneath an oak tree, the dead’s resting place must grant the living an opportunity to continue their devotions.

‘Children in the Churchyard’ as a Reflection on Death

Alfred F. Bellow’s illustration, ‘Children in the Churchyard,’ welcomes and invites viewers to reflect on death and burial rites. The reality is that death is inevitable, and the living have the unique opportunity to decide how to honor their ancestors. Perhaps the women adorning the grave with their floral wreath are a reflection of England, actively leading transatlantic nations with their steadfast customs. And perhaps the little boy within the illustration is not merely a young fellow playing in the background, avoiding the task at hand. Instead, consider the boy as a reflection of early America, eager to situate itself in the beauty of tradition — right on the cusp of finding its identity.

Source

Bellows, Alfred F. ‘Children in the Churchyard.’ in Irving, Washington. Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Artist’s Edition (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1864), p. 195. Courtesy HathiTrust.

References

Bellows, Alfred F. ‘Children in the Churchyard.’ Transatlantic Anglophone Literatures, 1776-1920: An Anthology, edited by Hughes, Linda K., et al. (Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh, 2022) pp. 496.

Eberwein, Jane D. ‘Transatlantic Contrasts in Irving’s “Sketch Book.’’ College Literature, vol. 15, no. 2, 1988, pp. 153–70.

French, Stanley. ‘The Cemetery as Cultural Institution: The Establishment of Mount Auburn and the “Rural Cemetery” Movement.’ American Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1, 1974, pp. 37–59.

Irving, Washington. The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Artist’s Edition. E-book, The Project Gutenberg, 2016.