The American River Ganges: Image Analysis

by Bridgett ‘Nikki’ Johnson

‘American River Ganges. The priests and the children.’ In Harper’s Weekly, vol. 15, no. 770, 30 September 1871.

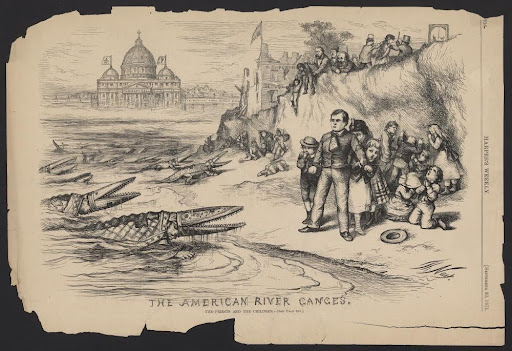

Thomas Nast was the most prominent political cartoonist after the Civil War. He was mainly featured in Harper’s Weekly, one of the most popular magazines in the United States during the 1800s. Nast was known for his ‘radical reformist views’ and most, if not all, had a ‘violent style’ (Jarman). Nast’s arguably most famous work is his cartoon titled ‘The American River Ganges. The priests and the children,’ printed in Harper’s Weekly in 1871. This political cartoon broadcast Nast’s views of ‘bringing all children together into the public sphere, under democratic control, [muting] their religious and racial differences and molding a unified, multiethnic American society’ (Justice 174). Additionally, Nast was known for his ‘vindictive caricatures of Irish Catholics’ both in the United States and abroad (176). His feelings surrounding Catholicism led to Nash creating one of his most famous works criticizing Catholicism and its purported desire to control what would be taught in public schools in America.

‘The American River Ganges’ shows how big a concern public education had become to Nast in the late 1800s. Nast’s cartoon shows a group of schoolchildren standing on the banks of a river as what appears to be alligators crawl out of the water towards them. Upon closer inspection, it is easy to see that the alligators are Catholic bishops wearing their religious garb, the mouths of the alligators being the pretiosa, a jewel-encrusted bishop’s mitre. The bodies of the alligators wear the bishop’s pontifical vestments, most likely a chasuble. These types of adornment are notably worn on holy holidays and feast days. The alligator priests slither out of the water towards the frightened children. The children are of different ethnicities, showcasing Nast’s ‘Radical Republican, utopian vision which held that public schools should be open to all children, regardless of race, creed or ethnicity’ (Kamphoefner).

Another feature of the image is the inclusion of Tammany Hall in the background, ‘a powerful agent in defining American democracy’ (O’Toole). Tammany Hall was a political machine that was run by the infamous William M. Tweed. Created by Irish-Americans, it started out as nothing more than a social club. It quickly became a ‘quintessential American political machine’ that primarily concerned itself with power above all else (Justice 187). Within Nast’s piece, Tweed features as the man lowering children down to allow the priests to attack them. According to Halloran, ‘Tweed was the symbol of civic corruption, not only in New York but nationwide, and his power was built on the violence of Irish street gangs’ (5).

Standing in front of the terrified children is a boy who appears to be slightly older. In his coat, the Protestant bible sticks out, showing that he is against the Catholic bishops slithering out of the water. This boy seemingly represents the Protestant teachings in public schools, and how these specific teachings are standing up against the allegiance to the monarchy (Kamphoefiner).

In the background of the image, Columbia, Nast’s symbol of American compassion and justice, can be seen being led to the gallows for trying to help the children (Kamphoefiner). Also in the background, a crumbling public school with an inverted American flag. It was Nast’s intention for this to be seen as a signal for help from a public school in the face of the Catholic church in Nast’s narrative.

Nast’s ‘The American River Ganges’ is a scathing political cartoon that calls attention to the common belief that the Catholic church of the 1800s had a desire to control the public school system in the United States. Each part of the image, from the priests being dehumanized and presented as alligators wearing their holy feast regalia, to Columbia – the symbol for American justice – being led away to be hanged for going against the views of Tammany Hall, creates a narrative of Thomas Nast’s views of Catholicism. This helped build the idea that Nast was against Catholicism and made ‘commentaries on the dangers of Roman Catholicism’ (Halloran 68).

‘The American River Ganges’ is not only just Nast’s opinion on Tweed, Catholicism, and the Irish-American population, but the image is a look into the past, and ‘a rich visual representation of Radical Republican views in the 1870s’ (Justice 172). Nast’s political cartoons were known to have elements of punishment against those with whom Nast disagreed (Jarman). No matter the view of the person interpreting the image, Nast’s political opinions are on full display in what is arguably his best work.

Source:

Nast, Thomas. ‘American River Ganges: the priests and the children.’ Harper’s Weekly, vol. 15, no. 770, 30 September 1871.

References:

Golway, Terrence. Machine Made: Irish America, Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern New York Politics. 2012.

Halloran, F. D. The Power of the Pencil: Thomas Nast and American Political Art. 2005.

Jarman, Baird. ‘The Graphic Art of Thomas Nast: Politics and Propriety in Postbellum Publishing.’ American Periodicals, vol. 20, no. 2, 2010, pp. 156–89.

Justice, Benjamin. ‘Thomas Nast and the Public School of the 1870s.’ History of Education Quarterly, vol. 45, no. 2, 2005, pp. 171–206.

Kamphoefner, Walter. ‘‘The American River Ganges” – 30 September, 1871.’ Illustrating Chinese Exclusion, 24 Aug. 2018, thomasnastcartoons.com/irish-catholic-cartoons/the-american-river-ganges-1871/#:~:text=The%20concern%20of%20Roman%20Catholic,Weekly%20published%20the%20image%20twice.

Nast, Thomas. ‘The American River Ganges. The priests and the children.’ Catholic Historical Research Center Digital Collections. https://omeka.chrc-phila.org/items/show/735

O’Toole, James M. ‘”Boss Tweed’s Lost World,” Machine Made: Tammany Hall and the Creation of Modern American Politics.’ America, vol. 212, no. 6, 2015, p. 33.