HEADNOTE

As an English Dissenter, William Blake condemned the abusive power of class privilege in England and the practice of slavery in American colonies. And although Blake’s works went largely unrecognized during his lifetime, Blake ‘put pressure on the constant attempt at the time to compare and contrast the suffering of enslaved Africans in the British colonies and that of British laborers in Britain’ (Gurton-Wachter, 532). When portraying the suffering of enslaved Africans or workers in Britain, authors often made use of spectacle to sensationalise suffering in order to appeal to reader sympathies. A common trope in Abolitionist writings in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this affective formula often nullified joy in order to emphasize the extreme suffering of injured people due to a belief that negative emotion is ideal for eliciting sympathy and instigating socio-political revolution. However, Blake reveals how the affective formula could ‘fail’ to produce the desired reaction in readers by placing pressure upon reader sympathies. Blake resists the affective formula, giving equal weight to suffering and joy because, rather than invoking only sympathy, Blake wants to cause discomforting feelings in readers so as to condemn the very institutions which defend suffering and abuse: the Church and King.

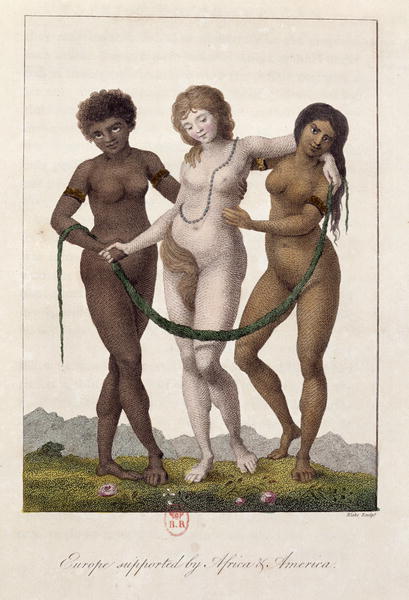

Published in its entirety in 1789, Songs of Innocence and Experience is a set of 26 poems illustrated by Blake himself. The collection is best known for its themes’ mythical dualism, supported by the two-part structure. ‘The Chimney Sweeper’, a poem in two parts (Innocence and Experience), concerns unethical child labour during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and condemns the British monarchy which permitted child labour. The poems utilise failed sympathy to condemn the King and Church as defenders of a faith which justifies violence and abuse of vulnerable peoples in England and abroad. Whereas the poems are most known for binary between innocence and experience (Paradisal vs Fallen, childhood vs adulthood, etc.), as transatlantic work, the poems also connect the justification of child labour in England with the slaves in colonial America through little Tom Dacre and the boy in black soot sold into labour. Indeed, Blake saw Europe as reliant upon those across the Atlantic, in America and Africa, as evidenced by the image ‘Europe Supported by Africa and America’, commissioned by John Gabriel Stedman in 1796 for his text, Narrative of a Five Years Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam.

Blake’s interest in failed sympathy and transatlanticism continues in his later works, as the ‘spirit of rebellion’ of the American Revolution inspires him to write America, a Prophecy, in 1793 on eighteen plates. America, A Prophecy foretells the downfall of English monarchal tyranny in a story, suggesting that the ‘spirit of rebellion’ in America travels through oceanic space, traversing the Atlantic. By situating America, A Prophecy and ‘The Chimney Sweeper’ with Stedman’s commissioned engraving in this entry, it becomes clear that Blake is simultaneously condemning the American sin of slavery and British child labour: he writes that the brothers of America are linked through heavy chains which flow from Albion across the Atlantic on Plate 3.

The cluster of entries which follow reveal Blake to be a transatlantic writer, working somewhat against the

oncoming sentimentalist movement of Romantic protest literature. Blake, as a pre-Romantic, does place value upon subjectivity, beauty, and imagination: Blake writes about his visions in addition to his more popular poetry, and numerous Blake critics mention his subsequent ‘un-worldly’ quality. Yet, as the excerpts below demonstrate, Blake does not fall prey to the affective formula that sentimentalism utilises. Rather, Blake portrays the ‘spirit of rebellion’ as an expression of both suffering and joy for injured or oppressed peoples, a spirit which he believes travels across the Atlantic. Accordingly, the excerpts affirm that the injured people Blake writes of – American colonists, slaves within the colonies, the English chimney sweep – are all transatlantic subjects engaging in the dual-natured spirit of rebellion, expressing both suffering and joy equally.

This entry was edited by Shelby Oubre.

Songs of Innocence (1789)

‘The Chimney Sweeper’

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue,

Could scarcely cry weep weep weep weep.1‘Weep’ here carries a double signification; the word refers to the weeping of children exploited through labour, and the young age of the boy who cannot properly pronounce ‘sweep’.

So your chimneys I sweep & in soot I sleep.

Theres2Blake was his own printer and publisher, often noted for his spelling and grammatical choices, such as a lack of apostrophe in contractions and the use of the ‘&’ symbol rather than the word ‘and’. little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head 10

That curl’d like a lambs back, was shav’d, so I said.

Hush Tom never mind it, for when your head’s bare,

You know that the soot cannot soil your white hair.

And so he was quiet, & that very night,

As Tom was a sleeping he had such a sight,

That thousands of sweepers Dick, Joe Ned & Jack

Were all of them lock’d up in coffins of black.3‘Coffins of black’ is sometimes glossed as a metaphor for the chimneys in which the sweeps worked, and possibly died, within.

And by came an Angel who had a bright key,

And he open’d the coffins & set them all free.

Then down a green plain leaping laughing they run

And wash in a river and shine in the Sun.

Then naked & white, all their bags left behind,4The reference to the color white implies a connection to race and labour, particularly, a connection between white English labourers and Black slaves.

They rise upon clouds, and sport in the wind.

And the Angel told Tom if he’d be a good boy,

He’d have God for his father & never want joy. 20

And so Tom awoke and we rose in the dark

And got with our bags & our brushes to work.

Tho’ the morning was cold, Tom was happy & warm,

So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.

Songs of Experience (1789)

‘The Chimney Sweeper’

A little black thing5Many scholars, like Lily Gurton-Wachter, treat the ‘little black thing’ as an allegory for African slaves in the American colonies. among the snow:

Crying weep, weep, in the notes of woe!

Where are thy father & mother? say?

They are both gone up to the church to pray.

Because I was happy upon the heath

And smil’d among the winters snow:

They clothed me in the clothes of death.

And taught me to sing the notes of woe.

And because I am happy. & dance & sing.

They think they have done me no injury: 10

And are gone to praise God & his Priest & King6The defenders of the Church of England (Church/Priest/King) were often a target of radical politics during the nineteenth century.

Who make up a heaven of our misery.

America, A Prophecy (1793)

The Guardian Prince of Albion7A poetic term for Great Britain. burns in his nightly tent,

Sullen fires across the Atlantic glow to America’s shore:

Piercing the souls of warlike men, who rise in silent

night,

Washington8George Washington (1732-1799) was a Founding Father and the first president of the United States of America., Franklin9Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) was a Founding Father of the United States of America and a polymath, Paine10 Thomas Paine (1737-1736) was an English-born American political activist and author of two popular pamphlets during the American Revolution, titled Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1775). & Warren11Warren is potentially one of two people who served as President of the revolutionary Massachusetts Provincial Congress (MPC), Joseph Warren and James Warren. Joseph Warren was in the MPC office from 2 May 1775 to 17 June 1775 when he died in combat during the American Revolution. James Warren was in the MPC office from 18 June 1775 to 25 October 1780, when the MPC was disbanded. It is likely, though, that since Blake is referencing the earlier days of the American Revolution, he is referring to Joseph Warren, who would have been a Patriot in the earlier days., Gates12Horatio Gates (1727–1806) was British-born but served as a general for the American army during the early years of the Revolutionary War.,

Hancock13 John Hancock (1737-1793) was a Patriot of the American Revolution most often remembered for his large and embellished signature on the Declaration of Independence. Hancock was very wealthy and served as the first and third governor of Massachusetts. & Green14Nathanael Greene (1742-1786) was one of George Washington’s most trusted officers and is best known for his command of the southern region of the Revolutionary War.;

Meet on the coast glowing with blood from Albions fiery

Prince.

Washington spoke; Friends of America look over the

Atlantic sea;

A bended bow is lifted in heaven, & a heavy iron chain

Descends link by link from Albions cliffs across the sea

to bind

Brothers & sons of America,15The ‘iron chain’ links across the sea refer to enslaved peoples from Africa; the image selected for this cluster depicts and supports the brotherhood, or ‘iron chain’, Blake believes exists between America and Africa. till our faces pale and

yellow;

Heads deprest, voices weak, eyes downcast, hands

work-bruis’d,

Feet bleeding on the sultry sands, and the furrows of the

whip

Descend to generations that in future times forget. —

The strong voice ceas’d; for a terrible blast swept over

the heaving sea;

The eastern cloud rent: on his cliffs stood Albions

wrathful Prince

A dragon form clashing his scales at midnight he arose,

And flam’d red meteors round the land of Albion

beneath.

His voice, his locks, his awful shoulders, and his glowing

eyes,

Appear to the Americans upon the cloudy night.

Solemn heave the Atlantic waves between the gloomy

nations,

Swelling, belching from its deep red clouds & raging

fires!

Albion is sick! America faints! enrag’d the Zenith16A point on an imaginary celestial sphere directly above a specific location. In this instance, the imaginary celestial sphere grows to encompass the Atlantic Ocean, and the zenith likely lies somewhere between America and England. grew.

As human blood shooting its veins all round the orbed17A reference to the sphere of heaven.

heaven

Red rose the clouds from the Atlantic in vast wheels of

blood

And in the red clouds rose a Wonder o’er the Atlantic

sea;

Intense! naked! a Human fire fierce glowing, as the

wedge —

Of iron heated in the furnace: his terrible limbs were fire

With myriads of cloudy terrors banners dark & towers

Surrounded; heat but not light went thro’ the murky

atmosphere18This could be a reference to the rapid industrialisation of England.

The King of England looking westward trembles at the

vision

Source Texts:

Blake, William. America, a Prophecy. [Lambeth, Printed by William Blake] Pdf. Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/48031339/>.

Blake, William, and Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection. Songs of Innocence. [London, 1789] Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/48031328/>.

Blake, William, Henry Crabb Robinson, and Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection. Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Shewing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. [London, W. Blake, 1794] Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/48031329/>.

‘Europe Supported by Africa and America, from ‘Narrative of a Five Years’ Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam 1772-77’, engraved by William Blake (1757-1827), published 1796 (coloured engraving)’.” Bridgeman Images: Charmet Collection, edited by Bridgeman Images, 1st edition, 2014.

References:

Erdman, David V. Blake, Prophet Against Empire: A Poet’s Interpretation of the History of His Own Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969).

Gilchrist, Alexander, and Ruthven Todd. Life of William Blake: By Alexander Gilchrist. Dent, 1945.

Gurton-Wachter, Lily. ‘Blake’s “Little Black Thing”: Happiness and Injury in the Age of Slavery’, ELH, Lessing J. Rosenwald Collection 87.2 (2020), pp. 519-52.

‘WILLIAM BLAKE, PAINTER AND POET’, Scribner’s Monthly 20.2 (June 1880), 225.

The William Blake Archive, www.blakearchive.org/.

‘THE WINDOW-SEAT.: THE CHIMNEY-SWEEPER. THE LITTLE BLACK BOY. THE LAMB’, The Riverside Magazine for Young People. An Illustrated Monthly 1.2 (February 1867), 9.

Wedmore, Frederick. ‘William Blake’, The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature 34.1 (July 1881), 104.