HEADNOTE

Born and raised in Manchester, England, Burnett moved to Tennessee and became a US citizen in the early 1900s. She would move back and forth from England to the US throughout her career, often visiting for more than a year at a time. In 1872 Burnett published “Surly Tim’s Trouble, A Lancashire Story,” showcasing the unfortunate sufferings of the title character as leading to the outward behavior that generated his nickname. Highlighting brutal and dangerous factory working conditions in England, Burnett focuses on the lower classes and the struggles of child labor, domestic abuse, sickness, and death they often faced in 19th-century Britain. Popular among readers on both sides of the Atlantic, “Surly Tim” became the title story for a collection of Burnett’s narratives published in both New York and London in 1877. In 1891, The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography dubbed this tale a “turning point” in Burnett’s “literary fortunes,” that “attracted great attention,” in part through her crafting of Tim’s “exquisitely pathetic English dialect” (“Burnett” 439).

Editorial work on this entry by Katie Marler and Toya Mary Okonkwo.

“Surly1Sulky and unfriendly Tim, A Lancashire2 Lancashire is a ceremonial county in northwest England Story” (1872)

Lancashire is a ceremonial county in northwest England Story” (1872)

- Frances Hodgson Burnett

- Cover for Little Lord Fauntleroy

- Cover for “Surly Tim”

‘Sorry to hear my fellow-workmen speak so disparagin’ o’ me? Well, Mester,’ that’s as it may be, yo know. Happen my fellow-workmen ha made a bit o’ a mistake—happen what seems loike crustiness3Outspoken and surly to them beant4Grumpy or intoxicated so much crustiness as summut5Something. Note: It helps to read parts of this story with dialect out loud. else—happen I mought do my bit o’ complainin’ too. Yo munnot trust aw yo hear, Mester; that’s aw I can say.’

I looked at the man’s bent face quite curiously, and, judging from its rather heavy but still not unprepossessing outline, I could not really call it a bad face, or even a sulky one. And yet both managers and hands had given me a bad account of Tim Hibblethwaite. ‘Surly Tim” they called him, and each had something to say about his sullen disposition to silence, and his short answers. Not that he was accused of anything like misdemeanor, but he was “glum loike,’ the factory people said, and “a surly fellow well deserving his name,’ as the master of his room had told me.

I had come to Lancashire to take the control of my father’s spinning-factory a short time before, and, being anxious to do my best toward the hands, I often talked to one after another in a friendly way, so that I could the better understand their grievances and remedy them with justice to all parties concerned.6Factory working conditions in England in the 19th century were brutal. Low wages, long hours, cruel discipline, and a fierce system of fines were common practices in the factory. So, in conversing with men, women, and children, I gradually found out that Tim Hibblethwaite was in bad odor, and that he held himself doggedly aloof from all; and this was how, in the course of time, I came to speak to him about the matter, and the opening words of my story are the words of his answer. But they did not satisfy me by any means. I wanted to do the man justice myself, and see that justice was done to him by others; and then again when, after my curious look at him, he lifted his head from his work and drew the back of his hand across his warm face, I noticed that he gave his eyes a brush, and, glancing at him once more, I recognized the presence of a queer moisture in them.

In my anxiety to conceal that I had noticed anything unusual, I am afraid I spoke to him quite hurriedly. I was a young man then, and by no means as self-possessed as I ought to have been.

‘I hope you won’t misunderstand me, Hibblethwaite,’ I said; ‘I don’t mean to complain—indeed, I have nothing to complain of, for Foxley tells me you are the steadiest and most orderly hand he has under him; but the fact is I should like to make friends with you all, and see that no one is treated badly. And somehow or other I found out that you were not disposed to feel friendly towards the rest, and I was sorry for it. But I suppose you have some reason of your own.’

The man bent down over his work again, silent for a minute, to my discomfiture,7Discomfort but at last he spoke, almost huskily.

‘Thank yo, Mester,” he said; “yo’re a koindly chap or yo wouldn’t ha noticed. An’ yo’re not fur wrong either. I ha reason o’ my own, tho’ I’m loike to keep ’em to mysen most o’ toimes. Th’ fellows as throw their slurs on me would na understond ’em if I were loike to gab, which I never were. But happen th’ toime ‘ll come when Surly Tim ‘ll tell his own tale, though I often think its loike it wunnot come till th’ Day o’ Judgment.’

‘I hope it will come before then,’ I said cheerfully. ‘I hope the time is not far away when we shall all understand you, Hibblethwaite. I think it has been misunderstanding so far which has separated you from the rest, and it cannot last always, you know.’

But he shook his head—not after a surly fashion, but, as I thought, a trifle sadly or heavily—so I did not ask any more questions, or try to force the subject upon him.

But I noticed him pretty closely as time went on, and the more I saw of him the more fully I was convinced that he was not so surly as people imagined. He never interfered with the most active of his enemies or made any reply when they taunted him and more than once I saw him perform a silent, half-secret act of kindness. Once I caught him throwing half his dinner to a wretched little lad who had just come to the factory, and worked near him; and once again, as I was leaving the building on a rainy night, I came upon him on the stone steps at the door bending down with an almost pathetic clumsiness to pin the woolen shawl of a poor little mite8A small child or animal, a term used especially when seeking sympathy9A homeless or helpless person, especially one who is abandoned or neglected who, like so many others, worked with her shiftless father and mother to add to their weekly earnings. It was always the poorest and least cared for of the children whom he seemed to befriend and very often I noticed that even when he was kindest, in his awkward man fashion, the little waifs were afraid of him, and showed their fear plainly.

The factory was situated on the outskirts of a thriving country town near Manchester,10 and at the end of the lane that led from it to the more thickly populated part there was a path crossing a field to the pretty church and church-yard, and this path was a short cut homeward for me. Being so pretty and quiet, the place had a sort of attraction for me, and I was in the habit of frequently passing through it on my way, partly because it was pretty and quiet, perhaps, and partly, I have no doubt, because I was inclined to be weak and melancholy at the time, my health being broken down under hard study.

and at the end of the lane that led from it to the more thickly populated part there was a path crossing a field to the pretty church and church-yard, and this path was a short cut homeward for me. Being so pretty and quiet, the place had a sort of attraction for me, and I was in the habit of frequently passing through it on my way, partly because it was pretty and quiet, perhaps, and partly, I have no doubt, because I was inclined to be weak and melancholy at the time, my health being broken down under hard study.

It so happened that in passing here one night, and glancing in among the graves and marble monuments as usual, I caught sight of a dark figure sitting upon a little mound under a tree and resting its head upon its hands, and in this sad-looking figure I recognized the muscular outline of my friend Surly Tim.

He did not see me at first, and I was almost inclined to think it best to leave him alone; but as I half turned away he stirred with something like a faint moan, and then lifted his head and saw me standing in the bright, clear moonlight.

‘Who’s theer?’ he said. ‘Dost ta want owt?’

‘It is only Doncaster, Hibblethwaite,’ I returned, as I sprang over the low stone wall to join him. ‘What is the matter, old fellow? I thought I heard you groan just now.’

‘Yo mought ha done, Mester,’ he answered heavily. ‘Happen tha did. I dunnot know mysen. Nowts th’ matter though, as I knows on, on’y I’m a bit out o’ soarts.’

He turned his head aside slightly and began to pull at the blades of grass on the mound, and all at once I saw that his hand was trembling nervously.

It was almost three minutes before he spoke again.

‘That un belongs to me,’ he said suddenly at last, pointing to a longer mound at his feet. ‘An’ this little un,’ signifying with an indescribable gesture the small one upon which he sat.

‘Poor fellow,’ I said, ‘I see now.’

‘A little lad o’ mine,’ he said, slowly ind tremulously. ‘A little lad o’ mine—an’ an’ his mother.’

‘What!’ I exclaimed, ‘I never knew that you were a married man, Tim.’

He dropped his head upon his hand again, still pulling nervously at the grass with the other.

‘Th’ law says I beant, Mester,’ he answered in a painful strained fashion. ‘I canna tell mysen what God-a’-moighty ‘ud say about it.’

‘I don’t understand,’ I faltered; ‘you don’t mean to say the poor girl never was your wife, Hibblethwaite.’

‘That’s what th’ law says,” slowly; ‘I thowt different mysen, an’ so did th’ poor lass. That’s what’s the matter, Mester: that’s th’ trouble.’

The other nervous hand went up to his bent face for a minute and hid it, but I did not speak. There was so much of strange grief in his simple movement that I felt words would be out of place. It was not my dogged inexplicable ‘hand’ who was sitting before me in the bright moonlight on the baby’s grave; it was a man with a hidden history of some tragic sorrow long kept secret in his homely breast—perhaps a history very few of us could read aright. I would not question him, though I fancied he meant to explain himself. I knew that if he was willing to tell me the truth it was best that he should choose his own time for it, and so I left him alone.

And before I had waited very long he broke the silence himself, as I had thought he would.

‘It wor welly about six year ago I cum ‘n here,’ he said, ‘more or less, welly about six year. I wor a quiet chap then, Mester, an’ had na many friends, but I had more than I ha’ now. Happen I wor better nater’d, but just as loike I wor loighter-hearted—but that’s nowt to do wi’ it.

‘I had na been here more than a week when theer comes a young woman to moind a loom i’ th’ next room to me, an’ this young woman bein’ pretty an’ modest takes my fancy. She wor na loike th’ rest o’ the wenches—loud talkin’ an’ slattern i’ her ways, she wor just quiet loike and nowt else. First time I seed her I says to mysen, ‘Theer’s a’ lass ‘at’s seed trouble;’ an’ somehow every toime I seed her afterward I says to mysen, ‘There’s a lass ‘at’s seed trouble.’ It wur in her eye—she had a soft loike brown eye, Mester—an’ it wur in her voice—her voice wur soft loike, too—I sometimes thowt it wur plain to be seed even i’ her dress. If she’d been born a lady she’d ha’ been one o’ th’ foine soart, an’ as she’d been born a factory-lass she wur one o’ th’ foine soart still. So I took to watchin’ her an’ tryin’ to mak’ friends wi’ her, but I never had much luck wi’ her till one neet I was goin’ home through th’ snow, and I seed her afore fighten’ th’ drift wi’ nowt but a thin shawl over her head; so I goes up behind her an’ I says to her, steady and respecful, so as she wouldna be feart, I says:—

‘’Lass, let me see thee home. It’s bad weather fur thee to be out in by thysen. Tak’ my coat an’ wrop thee up in it, an’ tak’ hold o’ my arm an’ let me help thee along.’

‘She looks up right straight forrad i’ my face wi’ her brown eyes, an’ I tell yo, Mester, I wur glad I wur an honest man ‘stead o’ a rascal, fur them quiet eyes ‘ud ha fun me out before I’d ha’ done sayin’ my say if I’d meant harm.’

‘ ‘Thaank yo kindly, Mester Hibblethwaite,’ she says, ‘but dunnot tak’ off tha’ coat fur me; I’m doin’ pretty nicely. It is Mester Hibblethwaite, beant it?’

‘ ‘Aye, lass,’ I answers, ‘it’s him. Mought I ax yo’re name.’

‘ ‘Aye, to be sure,’ said she. ‘My name’s Rosanna—’Sanna Brent th’ folk at th’ mill allus ca’s me. I work at th’ loom i’ th’ next room to thine. I’ve seed thee often an’ often.’

‘So we walks home to her lodgings, an’ on th’ way we talks together friendly an’ quiet loike, an’ th’ more we talks th’ more I sees she’s had trouble, an’ by an’ by—bein’ ony common workin’ folk, we’re straightforrad to each other in our plain way—it comes out what her trouble has been.

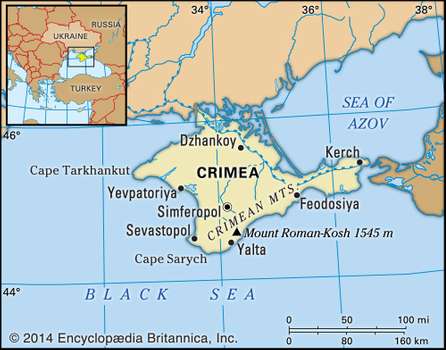

‘ ‘Yo p’raps wouldn’t think I’ve been a married woman, Mester,’ she says: ‘but I ha’, an’ I wedded an’ rued. I married a sojer when I wur a giddy young wench, four years ago, an’ it wur th’ worst thing as ever I did i’ aw my days. He wur one o’ yo’re handsome fastish chaps, an’ he tired o’ me as men o’ his stripe allers do tire o’ poor lasses, an’ then he ill-treated me. He went to th’ Crimea11 A region and peninsula of southern Ukraine on the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. From 1853 to 1856, the British and their allies fought against Russian forces in the Crimea. This conflict is known as the Crimean war. after we’n been wed a year, an’ left me to shift fur mysen. An’ I heard six month after he wur dead. He’d never writ back to me nor sent me no help, but I couldna think he wur dead till th’ letter comn. He wur killed th’ first month he wur out fightin’ th’ Rooshians. Poor fellow! Poor Phil! Th’ Lord ha mercy on him!’

A region and peninsula of southern Ukraine on the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. From 1853 to 1856, the British and their allies fought against Russian forces in the Crimea. This conflict is known as the Crimean war. after we’n been wed a year, an’ left me to shift fur mysen. An’ I heard six month after he wur dead. He’d never writ back to me nor sent me no help, but I couldna think he wur dead till th’ letter comn. He wur killed th’ first month he wur out fightin’ th’ Rooshians. Poor fellow! Poor Phil! Th’ Lord ha mercy on him!’

‘That wur how I found out about her trouble, an’ somehow it seemed to draw me to her, an’ make me feel kindly to’ards her, ‘t wur so pitiful to hear her talk about th’ rascal, so sorrowful an’ gentle, an’ not gi’ him a real hard word for a’ he’d done. But that’s allers th’ way wi’ women folk—th’ more yo harry’s them, th’ more they’ll pity yo an’ pray for yo. Why she wurna more then twenty-two then, an’ she must ha been now but a slip o’ a lass when they wur wed.

‘How-‘sever, Rosanna Brent an’ me got be good friends, an’ we walked home together o’ nights, an’ talked about our bits o’ wage, an’ our bits o’ debt, an’ th’ way th’ wench ‘ud keep me up i’ spirits when I wur a bit down-hearted about owt, wur just wonder. She wur so quiet an’ steady, an’ when she said owt she meant it, an’ she never said too much or too little. Her brown eyes allers minded me o’ my mother, though th’ old woman deed when I were nobbut a little chap, but I never seed ‘Sanna Brent smile ’bout thinkin’ o’ how my mother looked when I wur kneelin’ down sayin’ my prayers after her. An’ bein’ as th’ lass wi so dear to me, I made up my mind to ax her to be summat dearer. So once goin’ home along wi her, I takes hold o’ her han’ an’ lifts it up an’ kisses it gentle—as gentle an’ wi’ summat th’ same feelin’ as I’d kiss th’ Good Book.12The Bible

‘’Sanna,’ I says; ‘bein’ as yo’ve had so much trouble wi’ yo’re first chance, would yo’ be afeard to try a second? Could yo’ trust a mon again? Such a mon as me, ‘Sanna?’

‘ ‘I wouldna be feart to trust thee, Tim,’ she answers back soft an’ gentle after a manner. ‘I wouldna be feart to trust thee any time.’

‘I kisses her hand again, gentler still.

‘ ‘God bless thee, lass,’ I says. ‘Does that mean yes?’

‘She crept up closer to me i’ her sweet, quiet way.

‘ ‘Aye, lad,’ she answers. ‘It means yes, an’ I’ll bide by it’

‘ ‘An’ tha shalt never rue it, lass,’ said ‘Tha’s gi’en thy life to me, an’ I’ll gi’ mine to thee, sure and true.’

‘So we wur axed i’ th’ church t’ nex’ Sunday; an’ a month fra then we were wed an’ if ever God’s sun shone on a happy mon, it shone on one that day, when we come out o’ church together—me and Rosanna—an’ went to our bit o’ a home to begin life again. I couldna tell thee, Mester—there beant no words to tell how happy an’ peaceful we lived fur two year after that. My lass never altered her sweet ways, an’ I jus’ loved her to make up to her fur what had gone by. I thanked God-a’-moighty fur his blessing every day, an’ every day I prayed to be made worthy of it. An’ here’s jus’ wheer I’d like to ax a question, Mester, about summat ‘ats worretted me a good deal. I dunnot want to question th’ Maker, but I would loike to know how it is ‘at sometime seems ‘at we’re clean forgot—as if He couldna fash hissen about our troubles, an’ just loike left ’em to work out theirsens. Yo see, Mester, an’ we aw see sometime he thinks on us an’ gi’s us a lift, but hasna tha sen seen times when tha stopt short an’ axed thysen, ‘Wheer’s God-a’-moighty ‘at he didna straighten things out a bit? Th’ world’s i’ a power o’ a snarl. Th’ righteous are forsaken ‘n his seed’s beggin’ bread. An’ th’ devil’s topmost again.’ I’ve talked to th’ lass about it sometimes, an’ I dunnot think I meant harm, Mester, for I felt humble enough—an’ when I talked, my lass’d listen an’ smile soft an’ sorrowful, but never gi’ me but one answer.

‘ ‘Tim,’ she’d say, ‘this is on’y th’ skoo’ an’ we’re th’ scholars, an’ He’s teachin’ us His way. We munnot be loike th’ children of Israel i’ th’ Wilderness, an’ turn away fra th’ class ’cause o’ th’ Sarpent. We munnot say, ‘Theers a snake:’ we mun say, ‘Theers a Cross, an’ th’ Lord gi’ it to us.’ Th’ teacher wouldna be o’ much use, Tim, if th’ scholars knew as much as he did, an’ I allers think it’s th’ best to comfort mysen wi’ thinkin’, Th’ Lord-a’-moighty, he knows.’

‘An’ she allers comforted me too when I wor worretted. Life looked smooth somehow them three year. Happen th’ Lord put ’em to me to make up fur what wur comin.

‘At th’ eend o’ th’ first year th’ child wur born, th’ little lad here,’ touching the turf with his hand, ‘ ‘Wee Wattie’ his mother ca’d him, an’ he wur a fine lightsome little chap. He filled th’ whole house wi’ music day in an’ day out, crowin’ an’ crowin’—an’ cryin’ too sometime. But if ever yo’re a feyther, mester, yo’ll find out ‘at a baby’s cry ‘s music often enough, an’ yo’ll find, too, if yo ever lose one, ‘at yo’d give all yo’d getten jest to hear even th’ worst o’ cryin’. Rosanna she couldna find i’ her heart to set th’ little ‘un out o’ her arms a minnit, an’ she’d go about th’ room wi’ her eyes aw lighted up, an’ her face bloomin’ like a slip of a girl’s, an’ if she laid him i’ th’ cradle her head ‘ud be turnt o’er her shoulder aw’ th’ time lookin’ at him an’ singin’ bits o’ sweet-soundin’ foolish woman-folks’ songs. I thowt then ‘at them old nursery songs wur th’ happiest music I ever heard, an’ when ‘Sanna sung ’em they minded me o’ hymn-tunes.

‘Well, Mester, before th’ spring wur out Wee Wat was toddlin’ round holdin’ to his mother’s gown, an’ by th’ middle o’ th’ next he was cooin’ like a dove, an’ prattlin’ words i’ a voice like hers. His eyes wur big an’ brown an’ straightforrad like hers, an’ his mouth was like hers, an’ his curls wur the color o’ a brown bee’s back. Happen we set too much store by him, or happen it wur on’y th’ Teacher again teachin’ us his way, but how’sever that wur, I came home one sunny mornin’ fro’ th’ factory, an’ my dear lass met me at th’ door, all white an’ cold, but tryin’ hard to be brave an’ help me to bear what she had to tell.

‘ ‘Tim,’ said she, ‘th’ Lord ha’ sent us a trouble; but we can bear it together, canna we, dear lad?’

‘That wor aw, but I knew what it meant, though t’ poor little lamb had been well enough when I kissed him last.

‘I went in an’ saw him lyin’ theer on his pillows strugglin’ an’ gaspin’ in hard convulsions, an’ I seed aw’ was over. An’ in half an hour, just as th’ sun crept across th’ room an’ touched his curls, th’ pretty little chap opens his eyes aw at once.

‘ ‘Daddy!’ he crows out. ‘Sithee Dad—!’ an’ he lifts hissen up, catches at th’ floatin’ sunshine, laughs at it, and fa’s back—dead, Mester.

‘I’ve allers thowt ‘at th’ Lord-a’-moighty knew what he wur doin’ ‘when he gi’ th’ woman t’ Adam i’ th’ Garden o’ Eden. He knowed he wor nowt but a poor chap as couldna do fur hissen; an’ I suppose that’s th’ reason he gi’ th’ woman th’ strength to bear trouble when it comn. I’d ha’ gi’en clean in if it hadna been fur my lass when th’ little chap deed. I never tackledt owt i’ aw my days ‘at hurt me as heavy as losin’ him did. I couldna abear th’ sight o’ his cradle, an’ if ever I comn across any o’ his bits o’ playthings, I’d fall to cryin’ an’ shakin’ like a babby. I kept out o’ th’ way o’ th’ neebors’ children even. I wasna like Rosanna. I couldna see quoite clear what th’ Lord meant, an’ I couldna help murmuring sad and heavy. That’s just loike us men, Mester; just as if th’ dear wench as had give him her life fur food day an’ neet, hadna fur th’ best reet o’ th’ two to be weak an’ heavy-hearted.

‘But I getten welly over it at last, an’ we was beginnin’ to come round a bit an’ look forrad to th’ toime we’d see him agen ‘stead o’ lookin’ back to th’ toime we shut th’ round bit of a face under th’ coffin lid. Day comn when we could bear to talk about him an’ moind things he’d said an’ tried to say i’ his broken babby way. An’ so we were creepin’ back again to th’ old happy quiet, an’ we had been for welly six month, when summat fresh come. I’ll never forget it, Mester, th’ neet it happened. I’d kissed Rosanna at th’ door an’ left her standin’ theer when I went up to th’ village to buy summat she wanted. It wur a bright moon-light neet, just such a neet as this, an’ th’ lass had followed me out to see th’ moonshine, it wur so bright an’ clear; an’ just before I starts she folds both her hands on my shoulder an’ says, soft an’ thoughtful:—

‘ ‘Tim, I wonder if th’ little chap sees us?’

‘ ‘I’d loike to know, dear lass,’ I answers back. An’ then she speaks again:—

‘ ‘Tim, I wonder if he’d know he was ours if he could see, or if he’d ha’ forgot? He wur such a little fellow.’

‘Them wur th’ last peaceful words I ever heerd her speak. I went up to th’ village an’ getten what she sent me fur, an’ then I comn back. Th’ moon wur shinin’ as bright as ever, an’ th’ flowers i’ her slip o’ a garden wur aw sparklin’ wi’ dew. I seed ’em as I went up th’ walk, an’ I thowt again of what she’d said bout th’ little lad.

‘She wasna outside, an’ I couldna see a leet about th’ house, but I heerd voices, so I walked straight in—into th’ entry an into th’ kitchen, an’ theer she wur, Mester—my poor wench, crouchin’ down by th’ table, hidin’ her face i’ her hands, an’ close beside her wur a mon—a mon i’ red sojer clothes.13

‘My heart leaped into my throat, an fur a minnit I hadna a word, for I saw summat wur up, though I couldna tell what it wur. Bat at last my voice come back.

‘ ‘Good evenin’, Mester,’ I says to him; ‘I hope yo ha’ not broughten ill-news? What ails thee, dear lass?’

‘She stirs a little, an’ gives a moan like a dyin’ child; an’ then she lifts up her wan, broken-hearted face, an’ stretches out both her hands to me.

‘ ‘Tim,’ she says, ‘dunnot hate me, lad, dunnot. I thowt he wur dead long sin’. I thowt ‘at th’ Rooshans killed him an’ I wur free, but I amna. I never wur. He never deed, Tim, an’ theer he is—the mon as I wur wed to an’ left by. God forgi’ him, an’ oh, God forgi’ me!’

‘Theer, Mester, theer’s a story fur thee. What dost ta’ think o’t? My poor lass wasna my wife at aw—th’ little chap’s mother wasna his feyther’s wife, an’ never had been. That theer worthless fellow as beat an’ starved her an’ left her to fight th’ world alone, had comn back alive an’ well, ready to begin again. He could tak’ her awa’ fro’ me any hour i’ th’ day, an I couldna say a word to bar him. Th’ law said my wife—th’ little dead lad’s mother—belonged to him body an’ soul. Theer was no law to help—it wur aw on his side.

‘Theer’s no useo’ goin’ o’er aw we said to each other i’ that dark room theer. I raved an’ prayed an’ pled wi’ th’ lass to let me carry her across th’ seas, wheer I’d heerd theer was help fur such loike; but she pled back i’ her broken patient way that it wor na be reet, an’ happen it wur the Lord’s will. She didna say much to th’ sojer. I scarce heerd her speak to him more than once, when she axed him to let her go away by hersen.

‘ ‘Tha canna want me now, Phil,’ she said. ‘Tha canna care fur me. Tha now know I’m more this mon’s wife than tha’s. But I dunnot ax thee to gi me to him cause I know that wouldna be reet; I ax thee to let me aloan. I’ll go fur enow off an’ never see him more.’

‘But th’ villain held to her. If she diid come wi him, he said, he’d ha’ me up befo’ th’ court fur bigamy. I could ha’ done murder then, Mester, an’ I would ha’ done if it hadna been for th’ poor lass runnin’ in betwixt us an’ pleadin’ wi’ aw her might. If we’n been rich foak theer might ha’ been some help fur her, at least; th’ law might ha’ been browt to mak him leave her be, but bein’ poor workin’ foak theer was ony one thing: th’ wife mun go wi’ th’ husband, an’ theer th’ husband stood—a scoundrel, cursing, wi’ his black heart on his tongue.

‘ ‘Well,’ says th’ lass at last, fair wearied out wi’ grief, ‘I’ll go wi’ thee, Phil, an’ do my best to please thee, but I wum promise to forget th’ mon as has been true to me, an’ has stood betwixt me an’ th’ world.’

‘Then she turned round to me.’

‘ ‘Tim,’ she said to me, as if she wur haaf feart—aye, feart o’ him, an’ me standin’ by. Three hours afore, th’ law ud ha’ let me mill any mon ‘at feart her. ‘Tim,’ she says, ‘surely he wunnot refuse to let us go together to th’ little lad’s grave—fur th’ las’ time.’ She didna speak to him but to me an’ she spoke still an’ strained as if she wor too heart-broke to be wild. Her face was as white as th’ dead, but she didna cry, as any other woman would ha’ done. ‘Come, Tim,’ she said, ‘he canna say no to that.’

‘An’ so out we went ‘thout another word to an’ left th’ black-hearted rascal behind, sittin’ i’ th’ very room t’ little un deed in. His cradle stood theer i’ th’ corner. We went out into th’ moonlight ‘thout speakin’, an’ we didna say a word until we come to this very place, Mester.

‘We stood here for a minute silent, an’ then I sees her begin to shake, an’ she throws hersen down on th’ grass wi’ her arms flung o’er th’ grave, an’ she cries out as ef her death-wound had been give to her.

‘ ‘Little lad,’ she says, ‘little lad, dost ta see thee mother? Canst na tha hear her callin’ thee! Little lad, get nigh to th’ Throne an’ plead!’

‘I fell down beside o’ th’ poor crushed wench an’ sobbed wi’ her. I couldna comfort her, fur wheer wur there any comfort for us? Theer wur none left—theer wur no hope. We was shamed an’ broke down—our lives was lost. Th’ past wur nowt—th’ future wur worse. Oh, my poor lass, how hard she tried to pray—fur me, Mester—yes, fur me, as she lay theer wi’ her arms round ther dead babby’s grave, an’ her cheek on th’ grass as grew o’er his breast. ‘Lord God-a’-moighty,’ she says, ‘help us—dunnot gi’ us up—dunnot, dunnot. We canna do ‘thowt thee now, if th’ time ever wur when we could. Th’ little chap mun be wi’ Thee, I moind th’ bit o’ comfort about getherin’ th’ lambs i’ His bosom. An’, Lord, if Tha could spare him a minnit, send him down to us wi’ a bit o’ leet. Oh, Feyther! help th’ poor lad, there—help him. Let th’ weight fa’ on me, not on him. Just help th’ poor lad to bear it. If ever I did owt as wur worthy, i’ Thy sight, let that be my reward. Dear Lord-a’-moighty, I’d be willin’ to gi’ up a bit o’ my own heavenly glory fur th’ dear lad’s sake.’

‘Well, Mester, she lay theer on t’ grass prayin’ an cryin’, wild but gentle, fur nigh haaf an hour, an’ then it seemed ‘at she got quoite loike, an’ she got up. Happen th’ Lord had hearkened an’ sent th’ child—happen He had, fur when she getten up her face looked to me aw white an’ shinin’ i’ th’ clear moonlight.

‘ ‘Sit down by me, dear lad,’ she said, ‘an’ hold my hand a minnit.’ I set down an’ took hold of her hand, as she bid me.

‘ ‘Tim,’ she said, ‘this wur why th’ little chap deed. Dost na tha see now ‘at th’ Lord knew best?’

‘Yes, lass,’ I answers humble, an’ lays my face on her hand, breakin’ down again.

‘ ‘Hush, dear lad,’ she whispers, ‘we hannot time fur that. I want to talk’ to thee. Wilta listen?’

‘ ‘Yes, wife,’ I says, an’ I heerd her sob when I said it, but she catches hersen up again.

‘ ‘I want thee to mak’ me a promise,’ said she. ‘I want thee to promise never to forget what peace we ha’ had. I want thee to remember it allus, an’ to moind him ‘at’s dead, an’ let his little hand howd thee back fro’ sin an’ hard thowts. I’ll pray fur thee neet an’ day, Tim, an’ tha shalt pray fur me, an’ happen theer’ll come a leet. But ef theer dunnot, dear lad—an’ I dunnot see how theer could—if theer dunnot, an’ we never see each other agen, I want thee to mak’ me a promise that if tha sees th’ little chap first tha’lt moind him o’ me, and watch out wi’ him nigh th’ gate, and I’ll promise thee that if I see him first, I’ll moind him o’ thee an’ watch out true an’ constant.’

‘I promised her, Mester, as yo’ can guess, an’ we kneeled down an’ kissed th’ grass, an’ she took a bit o’ th’ sod to put i’ her bosom. An’ then we stood up an’ looked at each other, an’ at last she put her dear face on my breast an’ kissed me, as she had done every neet sin’ we were’mon an’ wife.

‘ ‘Good-bye, dear lad,’ she whispers—her voice aw broken. ‘Doant come back to th’ house till I’m gone. Good-bye, dear, dear lad, an’ God bless thee.’ An’ she slipped out o’ my arms an’ wur gone in a moment awmost before I could cry out.

••••••

‘Theer isna much more to tell, Mester—th’ eend’s comin’ now, an’ happen it’ll shorten off th’ story, so ‘at it seems suddent to thee. But it were na suddent to me. I lived alone here, an’ worked, an’ moinded my own business an’ answered no questions fur nigh about a year, hearin’ nowt, an’ seein’ nowt, an’ hopin’ nowt, till one toime when th’ daisies were blowin’ on th’ little grave here, theer come to me a letter fro’ Manchester fro’ one o’ th’ medical chaps i’ th’ hospital. It wur a short letter wi’ prent on it, an’ the moment I seed it I knowed summat wur up, an’ I opened it tremblin’. Mester, theer wur a woman lyin’ i’ one o’ th’ wards dyin’ o’ some long-named heart-disease, an’ she’d prayed ’em to send fur me, an’ one o’ th’ young soft-hearted ones had writ me a line to let me know.

‘I started aw’most afore I’d finished readin’ th’ letter, an’ when I getten to th’ place I fun just what I knowed I should. I fun Her—my wife—th’ blessed lass, an’ if I’d been an hour later I would na ha’ seen her alive, fur she were nigh past knowin’ me then.

“But I knelt down by th’ bedside an’ I plead wi’ her as she lay theer, until I browt her back to th’ world again fur one moment. Her eyes flew wide open aw’ at onct, an’ she seed me and smiled, aw her dear face quiverin’ i’ death.

‘ ‘Dear lad,’ she whispered, ‘th’ path was na so long after aw. Th’ Lord knew—he trod it hissen’ onct, yo’ know. I knowed tha’d come—I prayed so. I’ve reached th’ very eend now, Tim, an’ I shall see th’ little lad first. But I wunnot forget my promise—no. I’ll look out—for thee—for thee—at th’ gate.’

‘An’ her eyes shut slow an’ quiet, an’ I knowed she was dead.

‘Theer, Mester Doncaster, theer it aw is, for theer she lies under th’ daisies cloost by her child, fur I browt her here an’ buried her. Th’ fellow as come betwixt us had tortured her fur a while an’ then left her again, I fun out—an’ she were so afeard of doin’ me some harm that she wouldna come nigh me. It wur heart disease as killed her, th’ medical chaps said, but I knowed better—it wur heart-break. That’s aw. Sometimes I think o’er it till I canna stand it any longer, an’ I’m fain to come here an’ lay my hand on th’ grass,—an’ sometimes I ha’ queer dreams about her. I had one last neet. I thowt ‘at she comn to me aw at onct just as she used to look, ony, wi’ her white face shinin’ loike a star, an’ she says, ‘Tim, th’ path isna so long after aw—tha’s come nigh to th’ eend, an’ me an’ th’ little chap is waitin’. He knows thee, dear lad, fur I’ve towt him.’

‘That’s why I comn here to neet, Mester; an’ I believe that’s why I’ve talked so free to thee. If I’m near th’ eend I’d loike some one to know. I ha’ meant no hurt when I seemed grum an surly. It wurna14Wasn’t a ill-will, but a heavy heart.’

••••••

He stopped here, and his head drooped upon his hands again, and for a minute or so there was another dead silence. Such a story as this needed no comment. I could make none. It seemed to me that the poor fellow’s sore heart could bear none. At length he rose from the turf and stood up, looking out over the graves into the soft light beyond with a strange, wistful sadness.

‘Well, I mun go now,” he said slowly. “Good neet, Mester, good neet, an’ thank yo fur listenin’.’

‘Good night,’ I returned, adding, in an impulse of pity that was almost a passion, ‘And God help you!’

‘Thank yo again, Mester!’ he said, and then turned away; and as I sat pondering I watched his heavy drooping figure threading its way among the dark mounds and white marble, and under the shadowy trees, and out into the path beyond. I did not sleep well that night. The strained, heavy tones of the man’s voice were in my ears, and the homely yet tragic story seemed to weave itself into all my thoughts, and keep me from rest. I could not get it out of my mind.

In consequence of this sleeplessness I was later than usual in going down to the factory, and when I arrived at the gates I found an unusual bustle there. Something out of the ordinary routine had plainly occurred, for the whole place was in confusion. There was a crowd of hands grouped about one corner of the yard, and as I came in a man ran against me, and showed me a terribly pale face.

‘I ax pardon, Mester Doncaster,” he said in a wild hurry, ‘but theer’s an accident happened. One o’ th’ weavers is hurt bad an’ I’m goin’ fur th’ doctor. Th’ loom15An apparatus for making fabric by weaving yarn or thread caught an’ crushed him afore we could stop it.’

For some reason or other my heart misgave me that very moment. I pushed forward to the group in the yard-corner, and made my way through it.

A man was lying on a pile of coats in the middle of the bystanders, a poor fellow crushed and torn and bruised, but lying quite quiet now, only for an occasional little moan that was scarcely more than a quick gasp for breath. It was Surly Tim!

‘He’s nigh th’ eend o’ it now!’ said one of the hands pityingly. ‘He’s nigh th’ last now, poor chap! What’s that he’s sayin’, lads?’

For all at once some flickering sense seemed to have caught at one of the speaker’s words, and the wounded man stirred, murmuring faintly—but not to the watchers. Ah, no! to something far, far beyond their feeble human sight—to something in the broad Without.

‘Th’ eend!’ he said; ‘aye, this is th’ eend, dear lass, an’ th’ path’s aw shinin’ or summat an!—Why, lass, I can see thee plain, an’ th’ little chap too!’

Another flutter of the breath, one slight movement of the mangled hand, and I bent down closer to the poor fellow,—closer, because my eyes were so dimmed that I could not see.

‘Lads,’ I said aloud a few seconds later, ‘you can do no more for him. His pain is over!’

For with the sudden glow of light which shone upon the shortened path and the waiting figures of his child and its mother, Tim’s earthly trouble had ended.

Source Text:

Burnett, Frances Hodgson, ‘Surly Tim’s Trouble, “A Lancashire Story,”‘ (New York City: Scribner’s Monthly, Jun 1872), 220-233.

References:

‘Burnett, Frances Hodgson,’ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, edited by Distinguished Biographers from Each State, Vol. I. (New York: James White, 1891), 439-440.

‘Frances Hodgson Burnett,’ Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 Jan. 2016, www.britannica.com/biography/Frances-Hodgson-Burnett.

Gerzina, Gretchen, Frances Hodgson Burnett: The Unexpected Life of the Author of the Secret Garden, (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 2004).