HEADNOTE

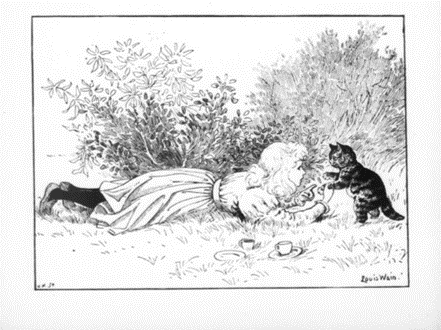

Like its author, “Little Betty’s Kitten Tells Her Story” is transatlantic in multiple ways. The story was first published in American periodical The Outlook in September 1894 before making its appearance in British periodical The English Illustrated Magazine in December of the same year. Also in December, the story was included in two collections of short stories, one edition published on each side of the Atlantic. The edition from The English Illustrated Magazine has been anthologized here due in part to its charming illustrations by Louis Wain. Wain earned his fame from his large-eyed drawings of cats and kittens, making his style well-fitted to Burnett’s children’s story.

The English Illustrated Magazine was a monthly, general-interest periodical that ran from October 1883 to August 1913. Though Burnett’s story envisioned child readers, the periodical itself was not a children’s magazine. Journalist and literary critic Clement King Shorter edited the publication when Burnett published this piece, though the periodical had six editors in total, including Shorter, during its run (Allingham). What set this magazine apart was its emphasis on publishing detailed illustrations and new fiction in addition to articles on nature, travel, current events, celebrities, and more (Allen). Its quality and quantity of illustrations and, later, photographs resulted in the price per issue increasing from one shilling to sixpence, making it one of the pricier periodicals on the market (Allingham). Burnett published this iteration of the story in a special Christmas issue. Her narrative opens the issue and is accompanied by numerous detailed illustrations of Betty, her kitten, and the roses she loved.

Burnett is particularly well-known for her garden writing, with her most lastingly famous work being The Secret Garden. Thus, it is no surprise that a garden and flowers, white roses in particular, play a significant role in this story. Recognizing the role of flowers in Victorian-era literature means considering their meanings within “flower language,” a practice popular during the Victorian era. Flower language itself has quite a transatlantic life. In addition to increasing globalism fostering a wider appreciation for exotic plants and flowers, it gave those wealthy enough to afford it the ability to collect rare specimens. Likewise, flower language itself first began in Turkey, and orientalist fascination with the practice led to its popularity among the wealthy in France, the US, and the UK alike (“Language”; Stott). Of course, there is debate about how often people actually put flower language into practice. It was primarily the hobby of wealthy women, as it necessitated purchasing expensive flower dictionaries in addition to the plants and flowers required to construct the desired message (“Language”). Burnett would have reasonably expected her readers to see the white roses at the center of the story as symbolizing purity, youth, and innocence, all embodied in the character of Betty.

Symbolically, the white roses are tied to Betty and her death. The roses reflect Betty’s purity, innocence, and youth. Throughout the 19th century, white children specifically were used to signify qualities such as innocence. Indeed, Robin Bernstein says: “Childhood was then understood not as innocent but as innocence itself; not as a symbol of innocence but as its embodiment” (4). Burnett’s characterization of Betty is just one of many examples of young white girls symbolizing purity and innocence in nineteenth-century transatlantic literature.

This entry was edited for the web by Saffyre Falkenberg. The editors have tried to replicate the source text’s positioning of the images as closely as possible.

Little Betty’s Kitten Tells Her Story

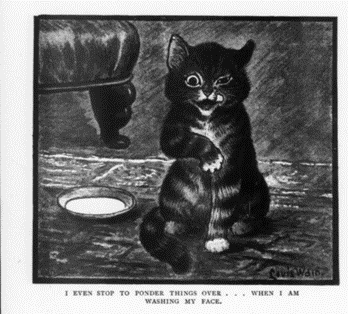

I am Betty’s kitten – at least I was Betty’s kitten once. That was more than a year ago. I am not a kitten now, I am a little cat, and I have grown serious, and think a great deal as I sit on the hearth-rug, looking at the fire and blinking my eyes. I have so much to think about that I even stop to ponder things over when I am lapping my milk or washing my face. I am very careful about lapping my milk. I never upset the saucer. Betty told me I must not. She used to talk to me about it when she gave me my dinner. She said that only untidy kittens were careless. She liked to see me wash my face, too, so I am particular about that. It is always Betty I am thinking about when I sit on the rug and blink at the fire. Sometimes I feel so puzzled and so anxious that if her mamma or papa are sitting near I look up at them and say –

I am Betty’s kitten – at least I was Betty’s kitten once. That was more than a year ago. I am not a kitten now, I am a little cat, and I have grown serious, and think a great deal as I sit on the hearth-rug, looking at the fire and blinking my eyes. I have so much to think about that I even stop to ponder things over when I am lapping my milk or washing my face. I am very careful about lapping my milk. I never upset the saucer. Betty told me I must not. She used to talk to me about it when she gave me my dinner. She said that only untidy kittens were careless. She liked to see me wash my face, too, so I am particular about that. It is always Betty I am thinking about when I sit on the rug and blink at the fire. Sometimes I feel so puzzled and so anxious that if her mamma or papa are sitting near I look up at them and say –

“Mee-aiow! Mee-aiow?”

But they do not seem to understand me as Betty did. Perhaps that is because they are grown-up people and she was a little girl. But one day her mamma said:

“It sounds almost as if she were asking a question.”

I was asking a question. I was asking about Betty. I wanted to know when she was coming back.

I know where she came from, but I do not know where she is gone, or why she went. She usually told me things, but she did not tell me that. I never knew her to go away before. I wish she had taken me with her. I would have kept my face and paws very clean and never have upset my milk.

I said I knew where she came from. She came from behind the white rose-bush before it began to bloom, and when it had nothing but glossy green leaves and tight little buds on it.

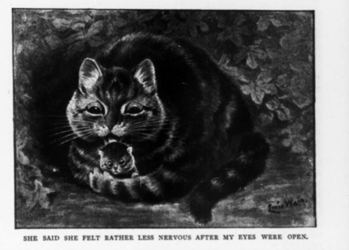

I saw her! My eyes had only been open about two weeks, and I was lying close to my mother in our bed under the porch that was round the house. It was a nice porch with vines climbing over it, and I was born under it. We were very comfortable there, but my mother was afraid of people. She was afraid lest they might come and look at us. She said I was so pretty that they would admire me and take me away. That had happened to two or three of my brothers and sisters before their eyes had opened, and it had made my mother nervous. She said the same thing had happened before when she had had families quite as promising, and many of her lady friends had told her that it continually happened to themselves. They said that people coming and looking at you when you had kittens was a sort of epidemic. It always ended in your losing children.

She talked to me a great deal about it. She said she felt rather less nervous after my eyes were opened because people did not seem to want you so much after your eyes were opened. There were fewer disappearances in families after the first nine days. But she told me she preferred that I should not be intimate with people who looked under the porch, and she was very glad when I could use my legs and get farther under the house when any one bent down and said, “Pussy! pussy!” She said I must not get silly and flattered and intimate even when they said, “Pretty pussy, poo’ ’ittle kitty puss!” She said it might end in trouble.

So I was very cautious indeed when I first saw Betty. I did not intend to be caught, but I was not so much afraid as I should have been if she had not been so very little and so pretty.

Not very long before she went away she said to me one day when we were in the swing together.

“Kitty, I am nearly five o’clock!”

So when she came from behind the white rose-bush perhaps she was four o’clock.

I shall never forget that morning. It was such a beautiful morning. It was in the early spring, and all the world seemed to be beginning to break into buds and blossoms. There were pink and white flowers on the trees, and there was such a delicious smell when one sniffed a little. Birds were chirping and singing, and every now and then darting across the garden. Flowers were coming out of the ground too, they were blooming in the garden beds and among the grass, and it seemed quite natural to see a new kind of flower bloom out on the rose-bush, which had no flowers on it then because the season was too early. I was such a young kitten that I thought the little face peeping round the green bush was a flower. But it was Betty, and she was peeping at me! She had such a pink bud of a mouth and such pink soft cheeks, and such large eyes, just like the velvet of a pansy blossom! She had a tiny pink frock and a tiny pink white apron with frills, and a pretty white muslin hat like a frilled daisy; and the soft wind made the curly soft hair falling over her shoulder as she bent forward sway as the vines sway.

“Mother!” I whispered, “what kind of a flower is that? I never saw one before.”

“Mother!” I whispered, “what kind of a flower is that? I never saw one before.”

She looked and began to be quite nervous.

“Ah, dear! ah, dear!” she said, “it is not a flower at all, it is a person, and she is looking at you!”

“Ah, mother!” I said, “how can it be a person when it is not half as high as the rose-bush! And it is such pretty colours. Do look again.”

“It is a child-person,” she said, “and I have heard they are sometimes the worst of all – though I don’t believe they take so many away at a time.” The little face peeped farther round the green of the rose-bush and looked prettier and prettier. The pink frock and white frills began to show themselves a little more.

“Get behind me,” said my mother, and I began to shrink back.

Ah, how often I have wondered since then why I did not know in a minute that it was Betty – just Betty! It seemed so strange that I did not know it without being told. She came nearer and nearer, and her cheeks seemed to grow pinker and pinker, and her eyes bigger and bigger. Suddenly she gave a little jump and began to clap her hands and laugh.

“Ah,” she said, “it is a little kitty. It is surely a little kitty.”

“Oh, my goodness!” said my mother. “Fts – fts – ftss! Ffttss – ffttssss!”

I could not help feeling as if it was rather rude of her, but she was so frightened.

But Betty did not seem to mind it at all. Down she went on her little knees on the grass, bending her head down to peep under the porch until her cheek touched the green blades and her heap of curls lay on the buttercups and daisies.

“Oh, you dee’ little kitty!” she said. “Pretty pussy, pussy, puss! Kitty – kitty! Poo ‘ittle kitty. I won’t hurt you!”

She made a movement as if she were going to put out her dimpled hand to stroke me, but a side window opened, and I heard a voice call to her –

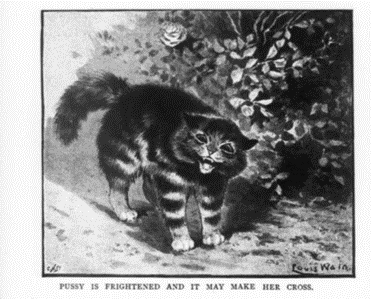

“Betty, Betty!” it said, “you mustn’t put your hand under there. The pussy is frightened, and it makes her cross, and she might scratch you. Don’t try to stroke her, dearie.”

She turned her bright little face over her shoulder.

“I won’t hurt her, mamma,” she said. “I surely, surely won’t hurt her. She has such a pretty kitty; come and look at it, mamma!”

“Ffttssss – ss!” said my mother. “More coming! Grown-ups this time!”

“I don’t believe they will hurt us,” I said. “The little one is such a pretty one.”

“You know nothing about it,” said my mother.

But they did not hurt us. They were as gentle as if they had been kittens themselves. The mother came and bent down by Betty’s side and looked at us too, but they did nothing which even frightened us. And they talked in quite soft voices.

“You see she is a wild little pussy,” the mother said. “She must have been left behind by the people who lived here before we came, and she has been living all by herself, and eating just what she could steal – or perhaps catching birds. Poor little cat! And now she is frightened because evidently some of her kittens have been stolen from her, and she wants to protect this one.”

“You see she is a wild little pussy,” the mother said. “She must have been left behind by the people who lived here before we came, and she has been living all by herself, and eating just what she could steal – or perhaps catching birds. Poor little cat! And now she is frightened because evidently some of her kittens have been stolen from her, and she wants to protect this one.”

“But if I don’t frighten her,” said Betty, “if I keep coming to see her and don’t hurt her, and if I bring her some milk and some bits of meat, won’t she get used to me, and let her kitten come out and play with me after a while?”

“Perhaps she will,” said the mother. “Poor pussy, puss, pussy, pretty pussy!”

She said it in such a coaxing voice that I quite liked her, and then Betty began to coax too, and she was so sweet and so like a kitten herself that I could scarcely help going a trifle nearer to her, and I found myself saying “Mee-ow” quite softly in answer.

And from that time we saw her every day ever so many times. She seemed never tired of trying to make friends with us. The first thing in the bright mornings we used to hear her pretty child voice and see her pretty child face. She used to bring saucers of delightful milk to us two or three times a day. And she always was so careful not to frighten us. “Pretty, pretty pussy; pretty kitty puss!” in a voice as soft as silk, and then she would put the saucer of milk near us and go away behind the rose-bush and let us drink in comfort and peace.

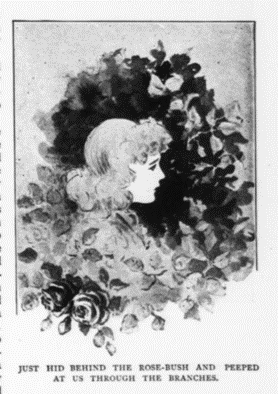

We thought at first that she went back to the house when she set the saucer down; but after a few days, when we were beginning to be rather less afraid, we found out that she just hid behind the rose-bush and peeped at us through the branches. I saw her pink cheeks and big soft pansy eyes one day, and I told my mother.

“Well, she is a well-behaved child-person,” mother said. “I sometimes begin to think she does not mean any harm.”

I was sure of it. Before I had lapped three saucers of milk I had begun to love her a little.

A few days later she just put the saucer down near us and stepped softly away, but stood right by the rose-bush without hiding behind it. And she said, “Pretty pussy – pussy!” so sweetly without moving towards us, that even my mother began to have confidence in her.

A few days later she just put the saucer down near us and stepped softly away, but stood right by the rose-bush without hiding behind it. And she said, “Pretty pussy – pussy!” so sweetly without moving towards us, that even my mother began to have confidence in her.

About that time I began to think it would be nice to creep out from under the house and get to know her a little better. It looked so pleasant and sunshiny out on the grass, and she looked so sunshiny herself. I did like her voice so, and I did like a ball I used to see her playing with; and when she bent down to look under the porch and her curls showing, I used to feel as if I should like to jump out and catch at them with my claws. There never was anything as pretty as Betty, or anything which looked as if it might be so nice to play with.

“I wish you would like me and come out and play, kitty,” she used to say to me sometimes. “I do so like kitties! I never hurt kitties. I’ll give you a ball of string.”

There was a fence not far from the house, and it had a sort of ledge on top, and it was a good deal higher than Betty’s head – because she was so very little. She was quite a little thing – only four o’clock.

So one morning I crept out from under my porch and jumped on to the top of that fence, and I was there when she came again to peep and say, “Pretty pussy.” When she caught sight of me she began to laugh and clap her little hands and jump up and down.

“Oh, there’s the kitty,” she said. “There’s my kitty. It has come out its own self. Kitty – kitty; pretty, pretty kitty!”

She ran to me, and stood beneath me looking up with her eyes shining and her pink cheeks full of dimples. She could not reach me, but she was so happy because I had come out that she could scarcely stand still. She coaxed me and called me pretty names, and stood on her tip-toes stretching her short arms and dimpled hand to try to see if I would let her touch me.

“I won’t pull you down, pussy,” she said, “I only want to stroke you. Oh, you pretty kitty!”

And I looked down at her and said “meeiou” gently, just to tell her that I wasn’t very much afraid now, and that when I was a little more used to being outside instead of under the house, perhaps I would play with her.

“Mee-iaou!” I said, and I even put out one paw as if I was going to give her a pat, and she danced up and down for joy.

My dear little Betty! I wish I could see her again. I cannot understand why she should go away when I loved her so much – and when everybody loved her so much.

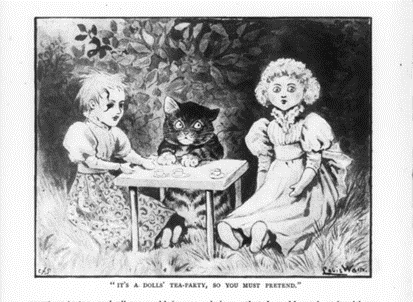

Oh, how happy we were when I came down from the fence. I did it in three days. She brought some milk and coaxed me, and then she put it on the grass close to the fence and moved away a few steps and looked at me with such a pretty imploring look in her pansy eyes that suddenly I made a little leap down and stood on the grass and began to lap the milk and even to purr! That was the beginning. From that time we played together aways. And oh, what a delightful playmate Betty was! And such a conversationalist! She was not a child who thought you must not talk to a kitten because it could not talk back. She had so many things to tell me and to show me. And she showed me everything and explained it all too. She had a playhouse in a box in a nice grassy, shady place, and she told me all about it and showed me her teacups and her dolls, and we had tea-parties with bits of real cake and tiny cups with flowers on them.

“They don’t hold much milk, kitty,” she said; “but it’s a dolls’ tea-party, so you must pretend and I’ll give you a big saucerful afterwards.”

I pretended as hard as ever I could, and it was a beautiful party, though I did not like the Sunday Doll, because she looked proud, and as if she thought kittens were too young. The Every-day Doll was much nicer, though her hair was a little tufty and she was cracked.

How Betty did enjoy herself that lovely sunny afternoon we had the first tea-party in the playhouse! How she laughed and talked and ran backwards and forwards to her mamma for the cups of milk and bits of cake! I ran after her every time, and she was as happy as a little bird.

“See how the kitty likes me now, mamma,” she said. “Just watch; it runs every time I run. It isn’t afraid of me the leastest bit! Isn’t it a pretty kitty?”

“See how the kitty likes me now, mamma,” she said. “Just watch; it runs every time I run. It isn’t afraid of me the leastest bit! Isn’t it a pretty kitty?”

I never left her when I could help it. She was such fun. She was a child who danced about and played a great deal, and I was a kitten who liked to jump. We ran about and played with balls, and we used to sit together in the swing. I did not like the swing very much at first, but I was so fond of Betty that I learned to enjoy it because she held me on her knee and talked. She had such a soft cosy lap and such soft arms, that it was delightful to be carried by her. She was very fond of carrying me about, and she liked me to lay my head on her shoulder so that she could touch me with her cheek! My pretty little Betty, she loved me so!

She used to show me the flowers in the garden, and tell me which ones were going to bloom and what colour they would be. We were very much interested in all the flowers, but we cared most about the white rose-bush. It was so big and we were so little, that we could sit under it together, and we were always trying to count the little hard green buds, though there were so many that we never counted half of them. Betty could only count up to ten, and all we could do was to keep counting ten over and over.

“These little buds will grow so big soon,” she used to say, “that they will burst, and then there will be roses, and more roses, and we will make a little house under here and have a tea-party.”

We were always going to look at that rose-bush, and sometimes, when we were playing and jumping, Betty would think she saw a bud beginning to come out, and we would both run.

I don’t know how many days we were so happy together playing ball and jumping in the grass and watching the white rose-bush to see how the buds were growing. Perhaps it was a long time, but I was only a kitten, and I was too frisky to know about time. But I grew faster than the rose-buds did. Betty said so! But oh, how happy we were! If it could only have lasted perhaps I might never have grown sober and sat by the fire thinking so much.

One afternoon we had the most beautiful play we had ever had. We ran after the ball, we swung together. Betty knelt down on the grass and shook her curly hair so that I could catch at it with my paws, we had a tea-party on the box, and when it was over we went to the rose-bush and found a bud beginning to be a rose. It was a splendid afternoon!

After we had found the bud beginning to be a rose we sat down together under the rose-bush. Betty sat on the thick green grass and I lay comfortably on her soft lap and purred.

After we had found the bud beginning to be a rose we sat down together under the rose-bush. Betty sat on the thick green grass and I lay comfortably on her soft lap and purred.

“We have jumped so much that I am a little tired, and I feel hot,” she said. “Are you tired, kitty? Isn’t it nice under the rose-bush? and won’t it be a beautiful place for a tea-party when all the white roses are out? Perhaps there will be some out to-morrow. We’ll come in the morning and see!”

Perhaps she was more tired than she knew. I don’t think she meant to go to sleep, but presently her head began to droop and her eyes to close, and in a little while she sank down softly and was quite gone.

I left her lap and crept up close to the breast of her little white frock and curled up in her arm and lay and purred and looked at her while she slept. I did so like to look at her. She was so pretty and pink and plump, and she had such a lot of soft curls. They were crushed under her warm cheek and scattered on the grass. I played with them a little while she lay there, but I did it very quietly, so that I should not disturb her.

She was lying under the white rose-bush, still asleep, and I was curled up against her breast watching her, when her mamma came out with her papa and they found us.

“Oh, how pretty!” the mamma said, “What a lovely little picture! Betty and her kitten asleep under the white-rose bush, and just one rose watching over them. I wonder if Betty saw it before she dropped off. She has been looking at the buds every day to see if they were beginning to be roses.”

“She looks like a rose herself,” said her papa, “but it is a pink one. How rosy she is!”

He picked her up in his arms and carried her into the house. She did not waken, and as I was not allowed to sleep with her, I could not follow, so I stayed behind under the rose-bush myself a little longer before I went to bed. When I looked at the buds I saw that there were several with streaks of white showing through the green, and there were three that I was sure would be roses in the morning, and I knew how happy

He picked her up in his arms and carried her into the house. She did not waken, and as I was not allowed to sleep with her, I could not follow, so I stayed behind under the rose-bush myself a little longer before I went to bed. When I looked at the buds I saw that there were several with streaks of white showing through the green, and there were three that I was sure would be roses in the morning, and I knew how happy

Betty would be and how she would laugh and dance when she saw them.

I often hear people saying to each other that they should like to understand the strange way I have of suddenly saying “Meeiaou! mee-iaou!” as if I was crying. It seems strange to me that they don’t know what it means. I always find myself saying it when I remember that lovely afternoon when we played so happily and Betty fell asleep under the rose-bush, and I thought how pleased she would be when she came out in the morning.

I can’t help it. Everything was so different from what I had thought it would be. Betty never came out in the morning. Oh dear! oh dear! she never came out again!

I got up early enough myself, and it was a beautiful, beautiful morning. There was dew on the grass and on the flowers, and the sun made it sparkle so that it was lovely to look at. I did so want Betty to see it. I ran to the white rose-bush, and sure enough there were four or five roses – such white roses and with such sparkling drops of dew on them.

I ran back to the house and called to Betty as I always did. I wanted her to come.

But she did not come! She was not even at breakfast eating her bread and milk. I looked for her everywhere except in her bedroom. Her bedroom door was closed, and I could not get in.

And though I called and called, nobody seemed to take any notice of me. Somehow something seemed to be the matter. The house was even quieter than usual, but I felt as if every one was busy and in trouble. I kept asking and asking where Betty was, but nobody would answer me. Once I went to her closed bedroom door and called her there, and told her about the white roses, and asked her why she did not come out. But before I had really finished telling her my feelings were quite hurt by her papa. He came and spoke to me in a way that was not kind.

“Go away, kitty,” he said. “Don’t make such a noise, you will disturb Betty.”

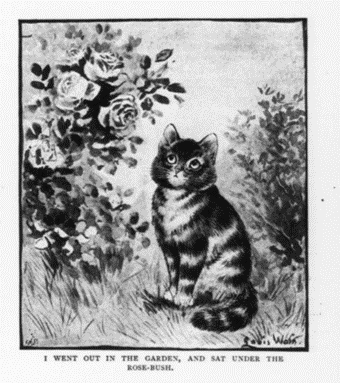

I went away waving my tail. I went out into the garden and sat under the rose-bush. As if I could disturb Betty! As if Betty did not always want me! She wanted me to sleep with her in her little bed, but her mamma would not let me.

But – ah! how could I believe it – she did not come out the next day, or the next, or even the next. It seemed as if I should go wild. People can ask questions, but a little cat is nothing to anybody unless to some one like Betty. She always understood my questions and answered them.

In the house they would not answer me. They were always busy and troubled. It did not seem like the same house. Nothing seemed the same. The garden was a different place. In the playhouse the Sunday Doll and the Every-day Doll sat and stared at the tea-things we had used that happy afternoon at the party. The Sunday Doll sat bolt upright and looked prouder than ever, as if she felt she was being neglected; but the Every-day Doll lopped over as if she had grieved her strength away because Betty did not come.

I had made up my mind at the first tea-party that I would never speak to the Sunday Doll, but one day I was so lonely and helpless that I could not help it.

“Oh dear!” I meeiaoued. “Oh dear! Do you know anything about Betty? Do you – do you?”

And that heartless thing only sat up and stared at me and never answered, though the tears were streaming down my nose.

What could a poor little cat do? I looked and looked everywhere but I could not find her. I went round the house and round the house and called in every room. But they only drove me out, and said I made too much noise, and never understood a word I said.

And the white rose-bush – it seemed as if it would break my heart. “There will be more roses, and more roses” Betty had said, and every morning it was coming true. I used to go and sit under it, and I had to count ten over and over and over, there were so many. It was such a great rose-bush that it looked at last like a cloud of snow-white bloom. And Betty had never seen it.

“Ah, Betty, Betty!” I used to cry when I had counted so many tens that I was tired. “Oh, do come and see how beautiful it is, and let us have our tea-party! Oh, White rose-bush, where is she?” They drove me out of the house so many times that I had no courage, but one morning the white rose-bush was so splendid that I made one desperate effort. I went to the bedroom door and rubbed against it and called with all my strength,

“Betty, if you are there – Betty, if you love me at all, oh speak to me and tell me what I have done! The white rose-bush has tens and tens and tens of flowers upon it. It is like snow. Don’t you care about it? Oh, do come out and see! Betty, Betty, I am so lonely for you, and I love you so!”

And the door actually opened , and her mamma stood there looking at me with great tears rolling down her cheeks. She bent down and took me in her arms and stroked me.

“Perhaps she will know it,” she said in a low strange voice to some one in the room. She turned and carried me into the bedroom, and I saw that it was Betty’s papa she had spoken to.

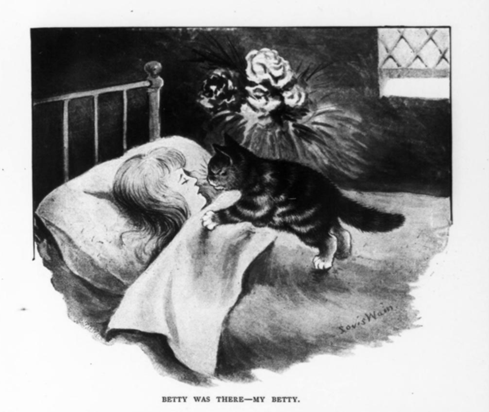

The next instant I sprang out of her arms on to the bed. Betty was there – my Betty!

It seemed as if I felt myself lose my senses. My Betty! I kissed her, and kissed her, and kissed her! I rubbed her little hands, her cheeks, her curls, I kissed her and purred and cried.

“Betty,” said her mamma, “Betty, darling, don’t you know your own little kitty?”

Why did not she? Why did she not? Her cheeks were hot and red, her curls were spread out over the pillow, her pansy eyes did not seem to see me, and her little head moved drearily to and fro.

Her mamma took me in her arms again, and as she carried me out of the room her tears fell on me.

“She does not know you, kitty,” she said. “Poor kitty, you will have to go away.”

“She does not know you, kitty,” she said. “Poor kitty, you will have to go away.”

* * * * * *

I cannot understand it. I sit by the fire and think and think, but I cannot understand. She went away after that, and I never saw her again.

I have never felt like a kitten since that time.

I went and sat under the white rose-bush all day, and slept there all night.

The next day there were more roses than ever, and I made up my mind that I would try to be patient and stay there and watch them until Betty came to see. But two or three days after, in the fresh part of the morning, when everything was loveliest, her mamma came out walking slowly straight towards the bush. She stood still a few moments and looked at it, and her tears fell so fast that they were like dew on the white roses as she bent over. She began to gather the prettiest buds and blossoms one by one. Her tears were falling all the time, so that I wondered how she could see what she was doing; but she gathered until her arms and her dress were full — she gathered every one! And when the bush was stripped of all but its green leaves I gave a little heart-broken cry – because they were Betty’s roses, and she had so loved them when they were only hard little buds, and she looked down and saw me, and oh! her tears fell then, not like dew, but like rain.

“Betty,” she said, “kitty, Betty has gone – where – where there are roses – always!”

And she went slowly back to the house, with all my Betty’s white roses heaped up in her arms. She never told me where my Betty had gone – no one did. And no more roses came out on the bush. I sat under it and watched because I hoped it would bloom again.

I sat there for hours and hours, and at last, while I was waiting, I saw something strange. People had been going in and out of the house all morning. They kept coming and bringing flowers, and when they went away most of them had tears in their eyes. And in the afternoon there were more than there had been in the morning. I had got so tired that I forgot and fell asleep. I don’t know how long I slept, but I was awakened by hearing many footsteps going slowly down the garden walk towards the gate.

They all seemed to be people who were going away. And first there walked before them two men who were carrying a beautiful white and silver box of some kind on their shoulders. They moved very slowly, and their heads were bent as they walked. But the white and silver box was beautiful. It shone in the sun, and – oh, how my heart beat! – all my Betty’s snow-white roses were heaped upon and wreathed around it. And I sat under the stripped rose-bush breaking my heart. She had gone away, my little Betty, and I did not know where, and all I could think was that this was the very last I should ever see of her because I thought there must be something which had belonged to her in the white and silver box under the roses, and because she was gone they were carrying that away too.

Oh, my Betty, my Betty! And I am only a little cat, who sits by the fire and thinks, while nobody seems to care or understand how lonely and puzzled I am and how I long for some kind person to explain. And I could not bear it, but that we loved each other so much that it comforts me to think of it. And I loved her so much that when I say to myself over and over again what her mamma said to me, it almost makes me happy again – almost – not quite, because I’m so lonely. But if it is true, even a little cat who loved her would be happy for her sake.

Oh, my Betty, my Betty! And I am only a little cat, who sits by the fire and thinks, while nobody seems to care or understand how lonely and puzzled I am and how I long for some kind person to explain. And I could not bear it, but that we loved each other so much that it comforts me to think of it. And I loved her so much that when I say to myself over and over again what her mamma said to me, it almost makes me happy again – almost – not quite, because I’m so lonely. But if it is true, even a little cat who loved her would be happy for her sake.

Betty has gone – where there are always roses. Betty has gone – where there are always roses.

Source Text:

Burnett, Frances Hodgson. “Little Betty’s Kitten Tells Her Story.” The English Illustrated Magazine, vol. 12, no. 135, 1894, pp. 3-12.

References

Allen, Moira. “Our Victorian Magazine Collection: The English Illustrated Magazine.” Victorian Voices, 2022, www.victorianvoices.net/magazines/EM.shtml.

Allingham, Philip V. “The English Illustrated Magazine.” The Victorian Web, 21 Aug. 2021, www.victorianweb.org/periodicals/englishillustrated/index.html

Bernstein, Robin. Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. New York University Press, 2011.

Stott, Romie. “How Flower-Obsessed Victorians Encoded Messages in Bouquets.” Atlas Obscura, 15 Aug. 2016, www.atlasobscura.com/articles/how-flowerobsessed-victorians-encoded-messages-in-bouquets.

“The Language of Flowers: Home.” The New York Botanical Garden, 3 Dec. 2021, www.libguides.nybg.org/languageflowers.