HEADNOTE

Though dissenting from Thomas Carlyle’s comments on American democracy in Latter Day Pamphlets (1850), the Saturday Evening Post (Philadelphia) nonetheless began by calling him ‘undoubtedly one of the most original and profound writers of the present age’ (‘Latter Day Pamphlets’, 2). Such esteem was widely shared in the US due to appreciation for Sartor Resartus (1833), Past and Present (1843), and other works. Carlyle’s initial essay in his series of 1850 pamphlets, ‘The Present Time’, belongs to the same approximate date as his ‘Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question’ (see SC, print anthology). Characterising Carlyle’s work at this time, Lowell Frye comments, ‘The despair and rage and occasionally even contempt audible in Carlyle’s style but equally evident in his ideas reveal a man who has given up on reasoned social and political discourse. Bereft of faith in democracy’ or the ability of ‘“the people”’ to choose ‘wise leaders or …freely follow them if selected’, Carlyle ‘contemplates and advocates authoritarian measures’ (Frye, 115). The US, Carlyle further contends, exemplifies democracy’s failings. Carlyle expected to offend with his pamphlet and did, both in the US and Britain. The Boston Liberator thundered, ‘He is vomiting forth, like another Vesuvius, red hot streams of lava upon all the humanitarian tendencies of the age’ (‘Thomas Carlyle’, 68), while the London Athenaeum critiqued his misplaced censure: ‘he falls foul of America,—not for her great (anti-democratic) sin, the slave system,—but because she is content to grow corn and cotton’ (‘Latter-Day’, 127). The excerpt below indicates how successfully the antebellum US was circulating its national identity as a democracy transatlantically, and Carlyle’s firm repudiation of both democracy and cosmopolitanism.

From ‘The Present Time’, Latter Day Pamphlets

[…]

Historically speaking, I believe there was no Nation that could subsist upon Democracy. Of ancient Republics, and Demoi and Populi,1Demoi: plural of ‘demos’, common people of an ancient Greek state (OED); Populi: people we have heard much; but it is now pretty well admitted to be nothing to our purpose;—a universal-suffrage republic, or a general-suffrage one, or any but a most limited-suffrage one, never came to light, or dreamed of doing so, in ancient times. When the mass of the population were slaves, and the voters intrinsically a kind of kings, or men born to rule others; when the voters were real ‘aristocrats’ and manageable dependents of such,—then doubtless voting, and confused jumbling of talk and intrigue, might, without immediate destruction, or the need of a Cavaignac2Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (1802-57), French general who suppressed workers during the 1848 revolution in France to intervene with cannon and sweep the streets clear of it, go on; and beautiful developments of manhood might be possible beside it, for a season. Beside it; or even, if you will, by means of it, and in virtue of it, though that is by no means so certain as is often supposed. Alas, no: the reflective constitutional mind has misgivings as to the origin of old Greek and Roman nobleness; and indeed knows not how this or any other human nobleness could well be ‘originated,’ or brought to pass, by voting or without voting, in this world, except by the grace of God very mainly; — and remembers, with a sigh, that of the Seven Sages themselves3Plato’s list of seven included Bias, Chilon, Cleobulus, Myson, Pittacus, Solon and Thales. no fewer than three were bits of Despotic Kings, Ƭύραννος, ‘Tyrants’ so-called (such being greatly wanted there); and that the other four were very far from Red Republicans,4Supporters of the 1848 European Revolutions; advocates of republics rather than monarchies if of any political faith whatever! We may quit the Ancient Classical concern, and leave it to College clubs and speculative debating societies, in these late days.

Of the various French Republics that have been tried, or that are still on trial, — of these also it is not needful to say any word. But there is one modern instance of Democracy nearly perfect, the Republic of the United States, which has actually subsisted for threescore years or more, with immense success as is affirmed; to which many still appeal, as to a sign of hope for all nations, and a ‘Model Republic.’ Is not America an instance in point? Why should not all Nations subsist and flourish on Democracy, as America does?

Of America it would ill beseem any Englishman, and me perhaps as little as another, to speak unkindly, to speak unpatriotically, if any of us even felt so. Sure enough, America is a great, and in many respects a blessed and hopeful phenomenon. Sure enough, these hardy millions of Anglosaxon5Carlyle here associates US citizens only with white descendants of Britain or Germany, omitting citizens of colour. men prove themselves worthy of their genealogy; and, with the axe and plough and hammer, if not yet with any much finer kind of implements, are triumphantly clearing out wide spaces, seedfields for the sustenance and refuge of mankind, arenas for

the future history of the world; — doing, in their day and generation, a creditable and cheering feat under the sun. But as to a Model Republic, or a model anything, the wise among themselves know too well that there is nothing to be said. Nay, the title hitherto to be a Commonwealth or Nation at all, among the έθνη6Nations of the world, is, strictly considered, still a thing they are but striving for, and indeed have not yet done much towards attaining. Their Constitution, such as it may be, was made here, not there; went over with them from the Old-Puritan English workshop, ready-made. Deduct what they carried with them from England ready-made,—their common English Language, and that same Constitution, or rather elixir of constitutions, their inveterate and now, as it were, inborn reverence for the Constable’s Staff;7Police force truncheon, both a weapon of enforcement and British badge of office prior to the earliest police uniforms (1829) two quite immense attainments, which England had to spend much blood, and valiant sweat of brow and brain, for centuries long, in achieving;—and what new elements of polity or nationhood, what noble new phasis8Obsolete form of ‘phase’ of human arrangement, or social device worthy of Prometheus or of Epimetheus,9Prometheus: Greek Titan who stole fire from Zeus and gave it to humankind; Epimetheus: brother to Prometheus and husband of Pandora, who opened the jar of all the world’s miseries and loosed them upon earth yet comes to light in America? Cotton-crops and Indian corn and dollars come to light; and half a world of untilled land, where populations that respect the constable can live, for the present, without Government: this comes to light; and the profound sorrow of all nobler hearts, here uttering itself as silent patient unspeakable ennui, there coming out as vague elegiac wailings, that there is still next to nothing more. ‘Anarchy plus a street-constable:’ that also is anarchic to me, and other than quite lovely!

I foresee too that, long before the waste lands are full, the very street-constable, on these poor terms, will have become impossible: without the waste lands, as here in our Europe, I do not see how he could continue possible many weeks. Cease to brag to me of America, and its model institutions and constitutions. To men in their sleep there is nothing granted in this world: nothing, or as good as nothing, to men that sit idly caucusing and ballotboxing on the graves of their heroic ancestors, saying, “It is well, it is well!” Corn and bacon are granted: not a very sublime boon,10Reward on such conditions; a boon moreover which, on such conditions, cannot last! No: America too will have to strain its energies, in quite other fashion than this; to crack its sinews, and all but break its heart, as the rest of us have had to do, in thousandfold wrestle with the Pythons and mud-demons, before it can become a habitation for the gods.11The god Apollo slew a giant python before founding his first temple below Mount Parnassus (a myth familiar from Thomas Keightley’s The Mythology of Ancient Greece and Italy, first published in 1831). America’s battle is yet to fight; and we, sorrowful though nothing doubting, will wish her strength for it. New Spiritual Pythons, plenty of them; enormous Megatherions,12Carlyle’s coinage, presumably for ‘megatherium’, a ‘giant ground sloth’ (OED) as ugly as were ever born of mud, loom huge and hideous out of the twilight Future on America; and she will have her own agony, and her own victory, but on other terms than she is yet quite aware of. Hitherto she but ploughs and hammers, in a very successful manner; hitherto, in spite of her ‘roast-goose with apple-sauce,’ she is not much.13Roast goose and applesauce was a Victorian stock phrase for the equivalent of a bountiful Christmas feast. ‘Roast-goose with apple-sauce for the poorest working-man:’ well, surely that is something,—thanks to your respect for the street-constable, and to your continents of fertile waste land;—but that, even if it could continue, is by no means enough; that is not even an instalment towards what will be required of you. My friend, brag not yet of our American cousins! Their quantity of cotton, dollars, industry and resources, I believe to be almost unspeakable; but I can by no means worship the like of these. What great human soul, what great thought, what great noble thing that one could worship, or loyally admire, has yet been produced there? None; the American cousins have yet done none of these things. “What they have done?” growls Smelfungus,14Originally the name given by novelist Laurence Sterne (1713-68) to Tobias Smollett (1721-71) for his carping criticisms in Travels through France and Italy (1764), Smelfungus was adopted by Carlyle for similarly irritable complainers (Cumming, 433-4). tired of the subject: “They have doubled their population every twenty years. They have begotten, with a rapidity beyond recorded example, Eighteen Millions of the greatest bores ever seen in this world before:—that, hitherto, is their feat in History!”—And so we leave them, for the present; and cannot predict the success of Democracy, on this side of the Atlantic, from their example.

Alas, on this side of the Atlantic and on that, Democracy, we apprehend, is forever impossible! So much, with certainty of loud astonished contradiction from all manner of men at present, but with sure appeal to the Law of Nature and the ever-abiding Fact, may be suggested and asserted once more. The Universe itself is a Monarchy and Hierarchy; large liberty of ‘voting’ there, all manner of choice, utmost free-will, but with conditions inexorable and immeasurable annexed to every exercise of the same. A most free commonwealth of ‘voters;’ but with Eternal Justice to preside over it, Eternal Justice enforced by Almighty Power! This is the model of ‘constitutions;’ this: nor in any Nation where there has not yet (in some supportable and withal some constantly-increasing degree) been confided to the Noblest, with his select series of Nobler, the divine everlasting duty of directing and controlling the Ignoble, has the ‘Kingdom of God,’ which we all pray for, ‘come,’ nor can ‘His will’ even tend to be ‘done on Earth as it is in Heaven’ till then.15Carlyle quotes from the Lord’s prayer. My Christian friends, and indeed my Sham-Christian and Anti-Christian, and all manner of men, are invited to reflect on this. They will find it to be the truth of the case. The Noble in the high place, the Ignoble in the low; that is, in all times and in all countries, the Almighty Maker’s Law.

To raise the Sham-Noblest, and solemnly consecrate him by whatever method, new-devised, or slavishly adhered to from old wont,16Custom this, little as we may regard it, is a practical blasphemy forevermore, and Nature will in no wise forget it. Alas, there lies the origin, the fatal necessity, of modern Democracy everywhere. It is the Noblest, not the Sham-Noblest; it is God Almighty’s Noble, not the Court-Tailor’s Noble, nor the Able-Editor’s Noble, that must, in some approximate degree, be raised to the supreme place; he and not a counterfeit,—under penalties! Penalties deep as death, and at length terrible as hell-on-earth, my constitutional friend!—Will the ballotbox raise the Noblest to the chief place; does any sane man deliberately believe such a thing? That nevertheless is the indispensable result, attain it how we may: if that is attained, all is attained; if not that, nothing. He that cannot believe the ballotbox to be attaining it, will be comparatively indifferent to the ballotbox. Excellent for keeping the ship’s crew at peace, under their Phantasm Captain; but unserviceable, under such, for getting round Cape Horn.17The southernmost point of South America, where the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans meet Alas, that there should be human beings requiring to have these things argued of, at this late time of day!

I say, it is the everlasting privilege of the foolish to be governed by the wise; to be guided in the right path by those who know it better than they. This is the first ‘right of man;’ compared with which all other rights are as nothing,—mere superfluities, corollaries which will follow of their own accord out of this; if they be not contradictions to this, and less than nothing! To the wise it is not a privilege; far other indeed. Doubtless, as bringing preservation to their country, it implies preservation of themselves withal; but intrinsically it is the harshest duty a wise man, if he be indeed wise, has laid to his hand. A duty which he would fain enough shirk; which accordingly, in these sad times of doubt and cowardly sloth, he has long everywhere been endeavouring to reduce to its minimum, and has in fact in most cases nearly escaped altogether. It is an ungoverned world; a world which we flatter ourselves will henceforth need no governing. On the dust of our heroic ancestors we too sit ballotboxing, saying to one another, It is well, it is well! By inheritance of their noble struggles, we have been permitted to sit slothful so long. By noble toil, not by shallow laughter and vain talk, they made this English Existence from a savage forest into an arable inhabitable field for us; and we idly dreaming it would grow spontaneous crops forever,—find it now in a too questionable state; peremptorily requiring real labour and agriculture again. Real ‘agriculture’ is not pleasant; much pleasanter to reap and winnow (with ballotbox or otherwise) than to plough!

Who would govern that can get along without governing? He that is fittest for it, is of all men the unwillingest unless constrained. By multifarious devices we have been endeavouring to dispense with governing; and by very superficial speculations, of laissez-faire,18The principle that government should not interfere with the action of individuals, esp. in industrial affairs and in trade (OED) supply-and- demand, &c. &c. to persuade ourselves that it is best so. The Real Captain, unless it be some Captain of mechanical Industry hired by Mammon,19Wealth, profit, possessions, etc., regarded as a false god or an evil influence (OED). Carlyle had earlier written of Captains of Industry as potential leaders in Past and Present (1843). where is he in these days? Most likely, in silence, in sad isolation somewhere, in remote obscurity; trying if, in an evil ungoverned time, he cannot at least govern himself. The Real Captain undiscoverable; the Phantasm Captain everywhere very conspicuous:—it is thought Phantasm Captains, aided by ballotboxes, are the true method, after all. They are much the pleasantest for the time being! And so no Dux or Duke of any sort, in any province of our affairs, now leads: the Duke’s Bailiff leads, what little leading is required for getting in the rents; and the Duke merely rides in the state coach. It is everywhere so: and now at last we see a world all rushing towards strange consummations, because it is and has long been so!

Source Text:

Carlyle, Thomas, Latter-Day Pamphlets (London: Chapman and Hall, 1850), pp. 21-28.

References:

Cumming, Mark (ed.), The Carlyle Encyclopedia (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004).

Frye, Lowell T., ‘“This Offensive and Alarming Set of Pamphlets”: Thomas Carlyle’s Latter-Day Pamphlets and the Condition of England in 1850’, Studies in the Literary Imagination 45.1 (2012), 113-38.

‘Latter Day Pamphlets’, Saturday Evening Post, 16 March 1850, 2.

‘Latter-Day Pamphlets.—No. I. The Present Time’, Athenaeum, 2 February 1850, 126-7.

‘Thomas Carlyle’, The Liberator, 26 April 1850, 68.

Images:

Carlyle, Thomas, ed. Latter-Day Pamphlets. London: Chapman and Hall, date. Title Page. Courtesy HaithiTrust.

Frontispiece, T. and R. Annan & Sons. Photograph of Thomas Carlyle from the Portrait by William Barr. In Chesterton, G. K., and J. E. Hodder Williams. Thomas Carlyle: With Numerous Illustrations. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1902. Courtesy Haithi Trust.

Portrait of Carlyle Engraved by F. Croll from a Daguerreotype by Beard. Rischgitz Collection. In Chesterton, G. K., and J. E. Hodder Williams. Thomas Carlyle: With Numerous Illustrations. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1902, 6. Courtesy Haithi Trust.

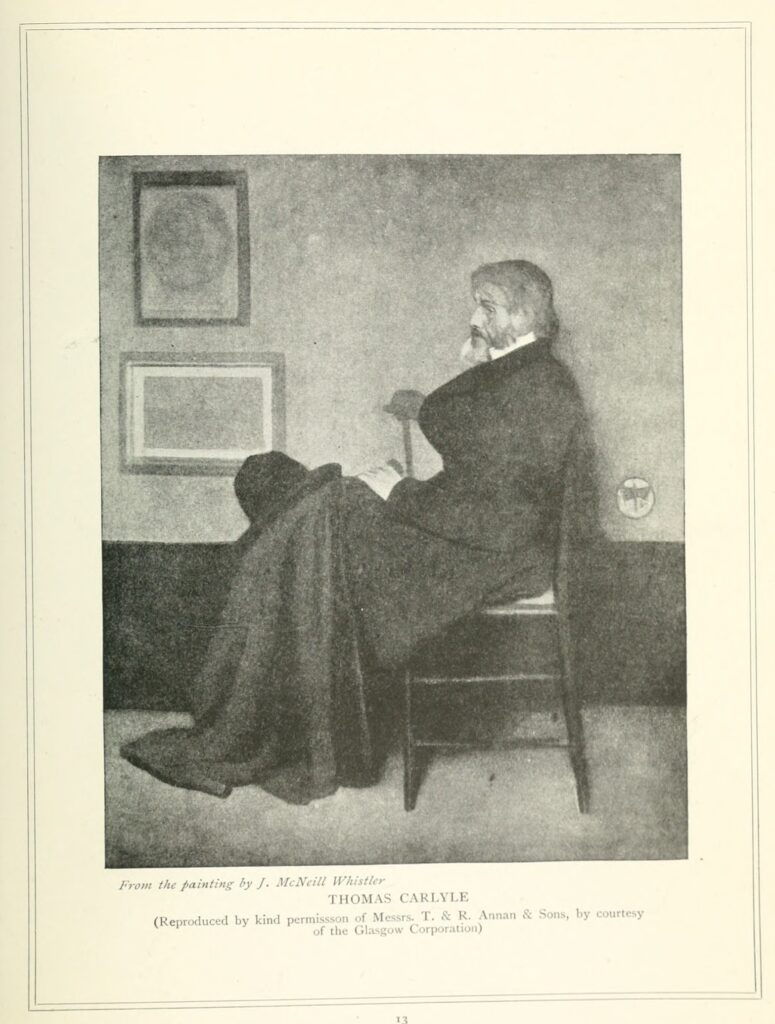

Thomas Carlyle. From the painting by J. McNeill Whistler. In Chesterton, G. K., and J. E. Hodder Williams. Thomas Carlyle: With Numerous Illustrations. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1902, 13. Courtesy Haithi Trust.