HEADNOTE

Socialism (the economic structure where the means of production, property, and firms are owned by the public) gained popularity in the nineteenth century as an alternative to capitalism, which began to generate startling new power dynamics through unequal wealth distribution and terrible conditions for the laboring class during the Industrial Revolution. Increasingly, philosophers, artists, and theorists alike explored socialism for its moral, cultural, and economic principles. One noteworthy supporter was H.G. Wells (1866-1946). Nicknamed the ‘Father of Science-Fiction’, Wells wrote iconic pieces such as The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and more; yet, what is sometimes less known today is the social commentary he often embedded within his stories.

Wells was a scientist who used scientific concepts to explore and critique the phenomena he saw happening in society in fictional scenarios; his techniques helped lay the foundation for science fiction as both a genre and an aesthetic. Wells’s pieces would become massively popular, with many being published across the Atlantic and around the globe, far from his home country of England. Literary figures lauded him as a pioneer of the science-fiction genre, theorists and philosophers acknowledged his notable contributions to the schools of thought surrounding socialism and society, and the general public knew him to be a captivating artist.

Van Wyck Brooks, author of the writing on Wells that we present below, was born in Plainfield, New Jersey, and after graduating from Harvard University, began a career in literature; specifically, critiques and biographies. His insightful analyses and biographies of established authors lent incredible insight into the craftsmanship and processes of their writing. Many credit Brooks for helping solidify various authors into the literary canon, as his publications would often expose both the general public and scholars alike to a particular writer’s talent and serious intellectual contributions, which may have been under appreciated at the time. One such example is The Ordeal of Mark Twain (1920), which examined Twain’s/Samuel Clemens’s style and how it intertwined (and sometimes clashed) with the famous author’s religious values.

Brooks published The World of H.G. Wells in 1915, twenty years after Wells’ first novel The Time Machine (1895) was released. Within two decades, Wells had become a household name on both sides of the Atlantic, making Brooks’ monograph particularly relevant at the time. However, the concept of socialism began to meet widespread resistance, especially in the United States, which was heavily ingrained in the culture of capitalism and industrialisation. Although the narratives of Wells were applauded, the social commentary infused within them met more criticism. The World of H.G. Wells analyzes and defends the philosophical, moral, and social arguments Wells makes pertaining to socialism for an increasingly hostile audience, while at the same time reviewing Wells’ skill and unique aestheticism of wondrous, scientific fantasies grounded by realistic and plausible settings.

The following excerpt is taken from the chapter ‘Towards Socialism.’

Editorial work on this entry by Mark Rose

From ‘Towards Socialism’ in The World of H.G. Wells (1915)

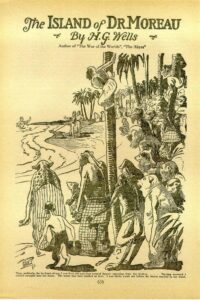

Introductory Illustration by Frank R. Paul. In H.G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau, Part I. Amazing Stories

Of all the battered, blurred, ambiguous coins of speech there is none so battered, blurred, and ambiguous as the word socialism. It mothers a dozen creeds at war with one another. And the common enemy looks on, fortified with the Socratic irony of the “plain man,” who believes he has at last a full excuse for not understanding these devious doings.

Therefore I take refuge in saying that H.G. Wells is an artist, neither more nor less, that socialism is to him at bottom an artistic idea, and that if it had not existed in the world he would have invented it. This clears me at once of the accusing frowns of any possible Marxian reader, and it also states a truth at the outset. For if the orthodox maintain that socialism is not an affair of choices, may I not retort that here actually is a mind that chooses to make it so? Here is an extraordinary kind of Utopian who has all the equipment of the orthodox and yet remains detached from orthodoxy. Orthodoxy is always jealous of its tabernacles and will not see itself dramatically; it has no concern with artistic presentations. But I protest there ought to be no quarrel here. If a socialism fundamentally artistic is an offence to the orthodox, let them accept it, without resentment, as a little harmless fun—all art being that.

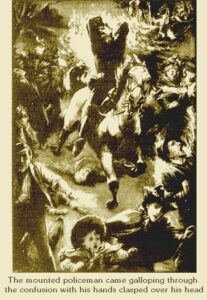

‘The mounted policeman came galloping through the confusion with his hands clasped over his head’. Illustration by Warwick Goble. In H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds.

Having said so much I return to my own difficulty, for it is very hard to focus H.G. Wells. He has passed through many stages and has not yet attained the Olympian repose. Artist as he is, he has been hotly entangled in practical affairs. There are signs in his early books that he once shared what Richard Jeffries1Richard Jefferies (1848-1887) was a Victorian author who focused on the English countryside and the natural/philosophical beauty embodied within it. called the “dynamite disposition,”—even now he knows, in imagination alone, the joy of black destruction. He has also been, and ceased to be, a Fabian2The Fabian Society, formulated in England 1884, was an organization that advocated for socialism through intellectual discourse and social institutions, as opposed to violent revolution, as favored by Marxists.. But it is plain that he has passed for good and all beyond the emotional plane of propaganda. He has abandoned working-theories and the deceptions of the intellect which make the man of action. He has become at once more practical and more mystical than a party programme permits one to be. Here is a world where things are being done—a world of which capital and labor are but one interpretation. How far can these things and the men who do them be swept into the service of the race? That is the practical issue in his mind, and the mystical issue lies in the intensity and quality of the way in which he feels it.

To see him clearly one has to remember that he is not a synthetic thinker but a sceptical artist, whose writings are subjective even when they seem to be the opposite, whose personality is constantly growing, expanding, changing, correcting itself (“one can lie awake at night and hear him grow,” as Chesterton3G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936), colloquially called the “Prince of Paradox”, was an English writer, journalist, theological scholar, and social theorist who created a wide array of works across genres and garnered universal praise. says), and who believes moreover that truth is not an absolute thing but a consensus of conflicting individual experiences, a “common reason” to be wrought out by constant free discussion and the comparison and interchange of personal discoveries and ideas. He is not a sociologist, but, so to say, an artist of society; one of those thinkers who are disturbed by the absence of right composition in human things, by incompetent draughtsmanship and the misuse of colors, who see the various races of men as pigments capable of harmonious blending and the planet itself as a potential work of art which has been daubed and distorted by ill-trained apprentices. In Wells this planetary imagination forms a permanent and consistent mood, but it has the consistency of a mood and not the consistency of a system of ideas. And though he springs from socialism and leads to socialism, he can only be called a socialist in the fashion—to adopt a violently disparate comparison—that St. Francis4St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226), a revered Saint in the Catholic Church, was widely known for his social contributions (such as animal and environmental activism) outside of his role as a religious figure. can be called a Christian. That is to say, no vivid, fluctuating human being, no man of genius can ever be embodied in an institution. He thinks and feels it afresh; his luminous, contradictory, shifting, evanescent impulses may, on the whole, ally him with this or that aggregate social view, but they will not let him be subdued to it. As a living, expanding organism he will constantly urge the fixed idea to the limit of fluidity. So it is with Wells. There are times when he seems as whimsical as the wind and as impossible to photograph as a chameleon.

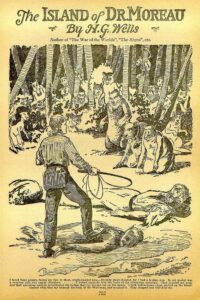

Introductory Illustration by Frank R. Paul. In H.G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau, Part II. Amazing Stories

Source Text:

Brooks, V. Wyck. ‘Towards Socialism’. The World of H.G. Wells (New York: M. Kennedy, 1915), 40-44. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t2n58ft9g&view=1up&seq=44

References:

Ahlquist, D. ‘Who is this Guy and Why Haven’t I Heard of Him?’ The Society of G.K.

Chesterton. https://www.chesterton.org/who-is-this-guy/

‘Our History’, Fabian Society. https://fabians.org.uk/about-us/our-history/

‘St. Francis of Assisi’, Catholic Online. https://www.catholic.org/saints/saint.php?saint_id=50

‘The Author-Richard Jefferies’, Richard Jefferies Museum. https://www.richardjefferies.org/the-author

‘Van Wyck Brooks [1886-1963]’, New Netherland Institute. https://www.newnetherlandinstitute.org/history-and-heritage/dutch_americans/van-wyck-brooks/

Image References:

Introductory Illustration by Frank R. Paul. In H.G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau, Part I. Amazing Stories 1.7 (October 1926), 636. Courtesy of Internet Archive.

Image Commentary: This image is the introductory illustration for Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, which comments on the fragility and artificiality of society, and how humans are still wild, primal animals at base. Social structure leads us to believe we are evolved, but when it dissolves, we revert to uncivilized impulses (shown through the ‘Beast-men’ creatures as they devolve through the story’s progression).

Introductory Illustration by Frank R. Paul. In H.G. Wells, The Island of Dr. Moreau, Part II. Amazing Stories 1.8 (November 1926), 702. Courtesy of Internet Archive.

‘The mounted policeman came galloping through the confusion with his hands clasped over his head’. Illustration by Warwick Goble. In H.G. Wells, The War of the Worlds. Pearson’s Magazine, III (April-December 1897). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_War_of_the_Worlds_by_Warwick_Goble_06.jpg

Image Commentary: This image is taken from Wells’ War of the Worlds, where Wells provides subtle commentary on imperialism (in the form of extraterrestrial Martians) and social anomie, as depicted in the image with a policeman, normally a figure of law and order, falling to the chaos of the situation like everyone else.