HEADNOTE

Much of Anna Barbauld’s literature for children, originally written in the late eighteenth century, was heavily inspired by her own life experience in teaching and in raising her nephew Charles. In 1775, Anna Barbauld and her husband established a boarding school that they managed until 1785. While a teacher there, Barbauld adopted her brother’s son as her own in 1777. During this decade, her experiences with children helped her produce Lessons for Children (1778) and Hymns in Prose for Children (1781), which greatly shifted the Anglo-American view of the role of children’s literature in society. Barbauld’s Lessons for Children became particularly popular across the Atlantic and promoted the parental role of educating children within the domestic sphere. Several American writers, such as Catharine Maria Sedgwick and Lydia Maria Child, praised Barbauld’s pedagogical texts in their own books in the early 1800s (Robbins). This movement toward women-led home-based education only grew in influence as Barbauld’s later writings took hold in both England and the US.

Title page of 1813 Boston edition. Aikin, Dr. [John] and Mrs. [Anna Laetitia Aikin Barbauld. Evenings at Home, or the Juvenile Budget Opened. Boston: Cummings and Hilliard, 1813.

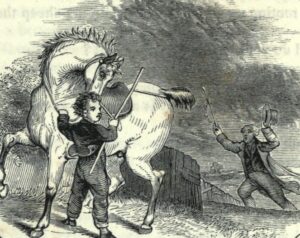

Meanwhile, illustrations began playing a more important role in children’s books, particularly in cultivating their allegiance with middle-class ideals. The illustrations in numerous editions of Evenings at Home portrayed a ‘sanitised and ideal world’ that young readers felt they could experience if they ‘willingly collude[ed] with the moral values embedded in the text’ (Brown, 425).

The following short story is a piece from Evenings at Home titled the ‘Little Philosopher’. It tells the story of a young boy who stops a man’s horse from running away, yet consistently refuses payment for his good deed. This specific text is part of the 1852 Revised Edition from the 15th London Edition and was also published in New York. The number of American editions circulating across the decades following the original London publication in 1796 reflects Barbauld’s and Aikin’s status during their lifetimes in transatlantic print culture. This text additionally underscores morals and social practices shared transatlantically from British to American households—the child-learned merits of frugality, hard work, and prompt transition to adulthood.

See also, in the print anthology, an excerpt from Barbauld’s Eighteen Hundred and Eleven, A Poem, in the NC section, and an excerpt from her influential primer, Lessons for Children, in the FD section. See too, in this section of the digital anthology, another entry from Evenings at Home, also in FD: ‘Flying Fish’.

Editorial work on this entry by Lauren Wahlstrom

‘The Little Philosopher’ from Evenings at Home (1796)

Initial page of ‘The Little Philosopher.’ Evenings at Home. Revised Edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852.

Mr. L. was one morning riding by himself, when dismounting to gather a plant in the hedge, his horse got loose and galloped away before him. He followed, calling the horse by his name, which stopped, but on his approach set off again. At length, a little boy in a neighbouring field, seeing the affair, ran across where the road made a turn, and getting before the horse, took him by the bridle, and held him till his owner came up. Mr. L. looked at the boy, and admired his ruddy, cheerful countenance.

“Thank you, my good lad!” said he; “you have caught my horse very cleverly. What shall I give you for your trouble?” putting his hand in his pocket.

Boy. I want nothing, sir.

Mr. L. Don’t you? so much the better for you. Few men can say as much. But pray, what are you doing in the field?

Boy. I was rooting up weeds and tending the sheep that are feeding on the turnips.

Mr. L. And do you like this employment?

Boy. Yes, very well, this fine weather.

Mr. L. But had you not rather play?

Boy. This is not hard work; it is almost as good as play.

Mr. L. Who set you to work?

Boy. My daddy, sir.

Mr. L. Where does he live?

Boy. Just by, among the trees there.

Mr. L. What is his name?

Boy. Thomas Hurdle.

Mr. L. And what is yours?

Boy. Peter, sir.

Mr. L. How old are you?

Boy. I shall be eight at Michaelmas.1Michaelmas is a Christian feast of St. Michael the Archangel that is typically celebrated on September 29th.

Mr. L. How long have you been out in this field?

Boy. Ever since six in the morning.

Mr. L. And are not you hungry?

Boy. Yes– I shall go to dinner soon.

Mr. L. If you had sixpence now, what would you do with it?

Boy. I don’t know. I never had so much in my life.

Mr. L. Have you no playthings?

Boy. Playthings! what are those?

Mr. L. Such as balls, nine-pins, marbles, tops, and wooden horses.

Boy. No, sir; but our Tom makes footballs to kick in the cold weather, and we set traps for birds; and then I have a jumping-pole and a pair of stilts to walk through the dirt with; and I had a hoop, but it is broke.

Mr. L. And do you want nothing else?

Boy. No. I have hardly time for those: for I always ride the horses to field, and bring up the cows, and run to the town of errands, and that is as good as play, you know.

Mr. L. Well, but you could buy apples or gingerbread at the town, I suppose, if you had money?

Boy. Oh– I can get apples at home; and as for gingerbread I don’t mind it much, for my mammy gives me a pie now and then, and that is as good.

Mr. L. Would you not like a knife to cut sticks?

Boy. I have one– here it is– brother Tom gave it me.

Mr. L. Your shoes are full of holes– don’t you want a better pair?

Boy. I have a better pair for Sundays.

Illustration of The Little Philosopher. Evenings at Home. Revised Edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852.

Mr. L. But these let in water.

Boy. Oh, I don’t care for that.

Mr. L. Your hat is all torn, too.

Boy. I have a better at home, but I had as leave have none at all, for it hurts my head.

Mr. L. What do you do when it rains?

Boy. If it rains very hard, I get under the hedges till it is over.

Mr. L. What do you do when you are hungry before it is time to go home?

Boy. I sometimes eat a raw turnip.

Mr. L. But if there are none?

Boy. Then I do as well as I can; I work on, and never think of it.

Mr. L. Are you not dry sometimes this hot weather?

Boy. Yes, but there is water enough.

Mr. L. Why, my little fellow, you are quite a philosopher!

Boy. Sir?

Mr. L. I say you are a philosopher, but I am sure you do not know what that means.

Boy. No, sir, no harm, I hope.

Mr. L. No, no! (laughing.) Well, my boy, you seem to want nothing at all, so I shall not give you money to make you want anything. But were you ever at school?

Boy. No, sir, but daddy says I shall go after harvest.

Mr. L. You will want books then.

Boy. Yes, the boys have all a spelling-book and a testament.2The Bible

Mr. L. Well, then, I will give you them– tell your daddy so, and that it is because I think you are a very good contented little boy. So now go to your sheep again.

Boy. I will, sir. Thank you.

Mr. L. Good-by, Peter.

Boy. Good-by, sir.

Portrait of Anna Laetitia Barbauld Engraved by J. Chapman, London: National Portrait Gallery, 1798.

Source Text:

Aikin, Dr. John and Mrs. Anna Laetitia Barbauld. “The Little Philosopher.” Evenings at Home. Revised Edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852. 213-215. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t6m04230q&view=1up&seq=225&skin=2021&q1=little%20philosopher

References:

Brown, Penny. “Capturing (and Captivating) Childhood: The Role of Illustrations in Eighteenth-Century Children’s Books in Britain and France.” Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 31, no. 3, Sept. 2008, pp. 419–49. EBSCOhost, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-0208.2008.00115.x.

Robbins, Sarah. “Re-Making Barbauld’s Primers: A Case Study in the Americanization of British Literary Pedagogy.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 4, 1996, pp. 158–69.

Rogers, Jacquelyn S. “Picturing the Child in Nineteenth-Century Literature.” Children and Libraries, 2008, pp. 41–46., https://www.ala.org/alsc/sites/ala.org.alsc/files/content/awardsgrants/profawards/bechtel/v6n1.pdf.

Image citations:

Title page of 1813 Boston edition. Aikin, Dr. [John] and Mrs. [Anna Laetitia Aikin Barbauld. Evenings at Home, or the Juvenile Budget Opened. Boston: Cummings and Hilliard, 1813. Courtesy of Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/eveningsathomeor01aiki_0/page/n5/mode/2up

Initial page of ‘The Little Philosopher.’ Evenings at Home. Revised Edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852. Courtesy HaithiTrust. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t6m04230q&view=1up&seq=225&skin=2021&q1=little%20philosopher

Illustration of The Little Philosopher. Evenings at Home. Revised Edition from the Fifteenth London Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1852. Courtesy HaithiTrust.https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc2.ark:/13960/t6m04230q&view=1up&seq=225&skin=2021&q1=little%20philosopher

Portrait of Anna Laetitia Barbauld Engraved by J. Chapman, cropped from original. Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository. London: National Portrait Gallery, 1798. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.